![]()

Chapter 1

Checkmate – the checklist phenomenon

In February 2006, I was invited to participate in a course to train surgeons in ‘non-technical skills’. The other invitees, numbering about fifteen, were senior consultant surgeons from a range of specialties.

At the start of the course, we were asked to watch a video of eight basketball players – half dressed in black and half in white – passing the ball to each other. The facilitator asked us to watch the clip carefully and to count the number of passes that the team in white made. The video lasted for only 2-3 minutes.

When the video ended, the facilitator asked, “How many passes did you see the team in white make?”

“Thirteen,” was our confident reply.

Without confirming whether this was the correct number of passes or not, the facilitator asked, “Did you see anything else in the video, apart from the players making the passes?”

None of us had.

“Are you sure that none of you noticed anything besides the players?”

Nobody responded to this question, as we didn’t want to appear to be foolish, in case we had missed something important.

“Didn’t you see a gorilla?” asked the facilitator.

“What? A gorilla?” We laughed, thinking that it must be some kind of joke.

“Yes,” said the facilitator, “there was a gorilla in the video. Didn’t you see it?”

We were a bit perplexed, and said, “No,” with a hint of disbelief.

“Now watch the clip again, this time without counting the passes,” said the facilitator.

When we watched the clip for the second time, everybody went quiet a few seconds after the clip had started. We saw a person wearing a gorilla suit enter from one corner. The gorilla walked to the centre, where players were making passes, stood there waving its hands, and then left the scene at the other corner, having been on screen for nearly ten seconds.

We were stunned when we saw the video again. We could not believe that we had missed such an obvious thing! One of the group said, “We surgeons consider ourselves good at picking up visual cues. This experiment shatters that belief!” It wasn’t the case that the gorilla was small and camouflaged against the players – in fact, it was quite prominent and hard to ignore, even for a casual observer. Still, us ‘careful observers’ had missed it.

It may be difficult to appreciate the experience of watching the video and the feeling of disbelief of missing the gorilla just by reading this description. If you are interested in watching this video, it is available on YouTube. Transport for London has adapted the experiment to educate the public about traffic awareness; it is available on http://www.dothetest.co.uk/. We think that we notice far more of the world around us than we actually do. Car drivers who crash into motorcycles often state that they did not see them, or that the motorcycle came out of nowhere, because they’re expecting and looking out for cars and not motorcycles.

The experiment on the surgical course was intended to make surgeons aware of the limitations of their powers of observation, however clever they may be. It was also intended to highlight the fact that, when we attend to a specific task, we overlook things that are out of range due to limited observation spans. The problem is that we are not aware that we are unable to see the whole picture. Until we come across situations like the ‘gorilla’ experiment, we assume that we see whatever is needed to be seen. We do not question surgeons’ abilities in these kinds of basic tasks. Obviously, these experiences challenge your views.

I have seen this video being shown to other groups of surgeons, and the results are the same every time. The more I observe surgeons watching the video, the more I see the wider implications of this experiment. The gorilla represents many other things that surgeons fail to notice. I realised that, on a broader scale, surgeons have focused their attention on counting the numbers (of passes), as in making technological advances but, have overlooked the ‘human factors’ in day to day practice (the gorilla). The gorilla symbolises all the non-technical aspects of surgical practice that surgeons take for granted – such as, as in this case, a surgeon’s cognitive skills. For all the astonishing surgical know-how we have accumulated, failures are still frequent in surgical practice. One of the reasons is increasingly evident – the volume and complexity of what is known exceeds the capacity of surgeons to deliver it. This is due to a lack of focus on human factors, at a systemic and individual level. The complexity of surgical practice has now overwhelmed the ability of an individual’s brain to manage it, however expert and specialised he may be. As a result, basic steps are sometimes missed, which are a matter of life and death for patients.

There is a reason to mention the gorilla experiment here. It is to do with the hullabaloo surrounding the WHO surgical checklist. If you look at the ‘surgical checklist’ as a tool to help us spot the ‘gorilla’ in operating theatres, you can see the correlation between the gorilla experiment and the checklist. There are some differences between the gorilla in the video and the gorillas in the operating theatres, however. At least the gorilla that you see in the video is harmless. It just stands in the centre, trying to show its presence. It neither disturbs the game nor bothers the players. However, the ‘gorillas’ in operating theatres are not necessarily benign. They don’t just stand by and let you do your business without disturbing you. They can create problems for us, and they do. They affect us – they have an impact on surgical outcomes, and yet still we fail to notice them, thinking that they are irrelevant. We remain busy counting passes, unaware that the gorilla may be disturbing the game. The checklist is supposed to spot the gorilla in the operating theatre before it creates any problems.

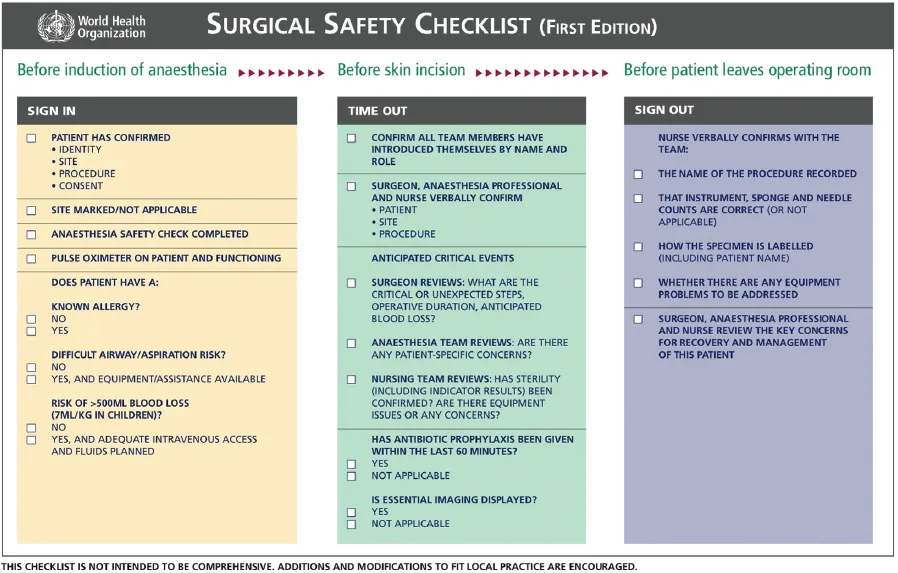

Reproduced with permission from http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/ss_checklist/en/index.html.

From the start of 2010, use of the surgical checklist has become mandatory in England and Wales. However, very few surgeons have been enthusiastic about its implementation. It has been in the news with conflicting comments. Some have described it as the biggest clinical innovation in the past 30 years, while others have dismissed it as just another ‘tick-box exercise’, favoured by hospital management who are keen to get mortality and morbidity figures down by the cheapest available means. Some have gone further in saying that these cheap ways of improving the results of surgery are an insult to the profession, while others have hailed the checklist as one of the greatest discoveries in the history of surgery, possibly even eclipsing the introduction of antisepsis, asepsis and antibiotics1. Having come across such diverse opinions, I decided to gather more information about the checklist project.

The surgical-checklist project was sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO). An international consultative process produced a nineteen-item surgical checklist which takes no longer than two minutes to apply2. The checklist is supposed to be applied at three points: during the pre-operative check-in phase; in the operating room prior to the surgical incision; and after the completion of the operation. The study involved eight centres from five continents and included places as diverse as teaching hospitals in North America and a rural hospital in Africa. St Mary’s Hospital in London was the pilot site in the UK. Lord Darzi was actively involved at a national, as well as international level, in this project. The study prospectively enrolled 7,688 adult patients undergoing surgery: 3,733 before the implementation of the checklist and 3,955 afterwards. The endpoints were compared for these two time periods.

Wondering why the WHO got involved in this venture, I became aware that, according to the WHO, the annual volume of major surgery was estimated at 234 million operations per year all over the world. Surgical deaths and complications have become a global public-health problem. Even in industrialised countries, the rate of complications from surgery ranges from 3-17%. To give you an example, in the United States, the state of Minnesota, which has less than 2% of the US population, reported 21 wrong-site surgeries in a single year. Remember, this is the reported incidence of an event that should never happen in the developed world. The real situation is probably even worse, because most critical incidents like these are not reported. According to the WHO, surgical complications contribute to approximately one million deaths around the world each year. As far as the situation in the UK is concerned, more than eight million patients undergo surgical procedures every year, equivalent to one in every eight people. In 2007 alone, 129,419 untoward surgical incidences were reported to the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA)3. Over 1,000 incidences resulted in severe harm and 271 led to the death of the patient. The WHO estimates that, each year, half a million – in other words, 50% – of the deaths related to surgery are preventable. Thus, as part of a global “Safe Surgery Saves Lives” programme, the WHO developed a simple, short checklist of guidelines for safe surgical procedures.

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine4, showed that use of the checklist reduced the rate of major complications by 36% (from 11% to 7%, p<0.001), deaths by 47% (from 1.5% to 0.8%, p=0.003), and infections by almost half. The reduction in deaths and complications was similar across all the hospitals in the study. The results were startling! If indeed 234 million surgical procedures are performed annually, and the average percentage of deaths can be reduced by 0.7%, that would mean that 1,638,000 lives could be saved worldwide and disabilities reduced by another few million. This too by using a method that takes just 90 seconds to use and it is free of charge!

If you are thinking that these results are too good to be true, you are not alone. Even the researchers did not expect such a profound effect5. They acknowledged that part of the improvement might result from the Hawthorne effect – an improvement in performance just because the individual is aware that he/she is being observed6. Sometimes people perform better when they are participants in an experiment. These individuals change their behaviour purely because of the attention they receive for a limited period. That being said, however, the Hawthorne effect is unlikely to have played a significant role in the case of the checklist. Since half of the participant surgeons were not keen about the use of the checklist at the start of the project, why would they bother to change their behaviour to please researchers who did not interest them? Dr Gawande, a lead researcher, revealed that he met significant resistance from participating surgeons, especially during the initial period of the study. About half of the surgeons said that the checklist made sense; of the other half, 30% were unenthusiastic but complied, while the remaining 20% said that they thought it was a waste of time and declined the invitation to participate. Although some surgeons refused to use the checklist initially, they became aware that the results were improving as they went along. By the end, only about 20% of surgeons said they didn’t like the checklist; interestingly, though, 93% said that they would want it used if they were undergoing an operation themselves! Let’s be honest – we don’t like checklists. They can be laborious. They’re not much fun. Some may see a checklist as an irritation and an incursion on their terrain. For others, the lack of enthusiasm is most likely an expression of a belief that the process is little more than a distraction. It is understandable that there will be resistance to adopting something as mundane as a checklist. Early adopters will already be using them. Some will be convinced by the research evidence, while others will want data from their own practice. But a few will see checklists as an insult to their professionalism and will never be convinced.

We are missing an important point (again, a gorilla point!) in the midst of these different opinions about the merits and demerits of the checklist and the appropriateness of the results of the study. The important point is, a simple intervention to change a practice behaviour can make a big impact on surgical outcome. What the checklist did was to bring about a change in the behaviour of the operating team. It changed what is known as ‘team cognition’ – in other words, the collective thinking of the entire team. You can imagine that if such a transient change in the behaviour of the surgical team could have so significant impact, what would happen if the behaviour changed for a sustained period? We might assume that the change in behaviour of the operating team members was due to the Hawthorne effect, but why should we not then think about...