- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

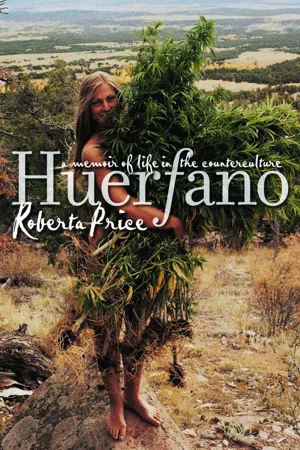

In the late 1960s, new age communes began springing up in the American Southwest with names like Drop City, New Buffalo, Lama Foundation, Morning Star, Reality Construction Company, and the Hog Farm. In the summer of 1969, Roberta Price, a recent college graduate, secured a grant to visit these communities and photograph them. When she and her lover David arrived at Libre in the Huerfano Valley of southern Colorado, they were so taken with what they found that they wanted to participate instead of observe. The following spring they married, dropped out of graduate school in upstate New York, packed their belongings into a 1947 Chrysler Windsor Coupe, and moved to Libre, leaving family and academia behind.

Huerfano is Price's captivating memoir of the seven years she spent in the Huerfano ("Orphan") Valley when it was a petrie dish of countercultural experiments. She and David joined with fellow baby boomers in learning to mix cement, strip logs, weave rugs, tan leather, grow marijuana, build houses, fix cars, give birth, and make cheese, beer, and furniture as well as poetry, art, music, and love. They built a house around a boulder high on a ridge overlooking the valley and made ends meet by growing their own food, selling homemade goods, and hiring themselves out as day laborers. Over time their collective ranks swelled to more than three hundred, only to diminish again as, for many participants, the dream of a life of unbridled possibility gradually yielded to the hard realities of a life of voluntary poverty.

Price tells her story with a clear, distinctive voice, documenting her experiences with photos as well as words. Placing her story in the larger context of the times, she describes her participation in the antiwar movement, the advent of the women's movement, and her encounters with such icons as Ken Kesey, Gary Snyder, Abbie Hoffman, Stewart Brand, Allen Ginsburg, and Baba Ram Dass.

At once comic, poignant, and above all honest, Huerfano recaptures the sense of affirmation and experimentation that fueled the counterculture without lapsing into nostalgic sentimentality on the one hand or cynicism on the other.

Huerfano is Price's captivating memoir of the seven years she spent in the Huerfano ("Orphan") Valley when it was a petrie dish of countercultural experiments. She and David joined with fellow baby boomers in learning to mix cement, strip logs, weave rugs, tan leather, grow marijuana, build houses, fix cars, give birth, and make cheese, beer, and furniture as well as poetry, art, music, and love. They built a house around a boulder high on a ridge overlooking the valley and made ends meet by growing their own food, selling homemade goods, and hiring themselves out as day laborers. Over time their collective ranks swelled to more than three hundred, only to diminish again as, for many participants, the dream of a life of unbridled possibility gradually yielded to the hard realities of a life of voluntary poverty.

Price tells her story with a clear, distinctive voice, documenting her experiences with photos as well as words. Placing her story in the larger context of the times, she describes her participation in the antiwar movement, the advent of the women's movement, and her encounters with such icons as Ken Kesey, Gary Snyder, Abbie Hoffman, Stewart Brand, Allen Ginsburg, and Baba Ram Dass.

At once comic, poignant, and above all honest, Huerfano recaptures the sense of affirmation and experimentation that fueled the counterculture without lapsing into nostalgic sentimentality on the one hand or cynicism on the other.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Huerfano by Roberta M. Price in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781613762530Subtopic

Social Science Biographies1 : Shop Around

April 1, 1970

David and I are leaving graduate school at Buffalo for good and moving to a hippie commune in southeastern Colorado. We’re twenty-four, and we’ve come of age in the third quarter of the twentieth century, when many of us have the opportunity to make passionate choices. We haven’t told our graduate school friends about our decision straight out, although we’ve told them about discovering Libre last summer, when we were traveling around Colorado and New Mexico on a SUNY Buffalo faculty fund grant to study the communes that were sprouting up in the Southwest. Libre, which means “free” in Spanish, is in the Huerfano Valley in southern Colorado. The Huerfano—the Orphan Valley. The valley and the Huerfano River running through it share the name of the lone butte that stands east of the valley, looking eastward into the Great Plains.

When we got back to Buffalo, we showed our slides of Libre and Drop City and New Buffalo. The brilliant colors of the Southwest bloomed on the walls of our apartment and classrooms during the long, dark Buffalo winter. We showed pictures of the Huerfano, a relatively narrow valley with sides that slope up like the sides of a teacup, rimmed by mountain ranges. We showed pictures of contemporaries making adobe bricks, irrigating corn, playing guitars, laughing into the camera. We told everyone how in the West you could stand on a mountain and see forever. When we returned to Libre last winter, on another grant to study communes, we felt certain we’d go back there permanently, but we weren’t sure when.

On the way back to Buffalo from Libre this winter, we detoured to the Grand Canyon on a late January weekday afternoon. The light was wintry but bright, and there were no other tourists on the south rim. Shoulder to shoulder we looked down through a space that is time to the glinting line of the Colorado River.

“Across the Great Divide,” David said.

“So, do you think we’ll actually move to Libre?” I asked, looking down at a hawk, swooping across the canyon below us.

“I guess so. It’s our only real option, don’t you think?” David said.

“Yes,” I agreed. “It’s where I want to wake up every morning. It’s where I can be the way I want to be.” Against the canyon’s grandeur, these words felt like a betrothal to me.

Back in Buffalo, we try to keep our options open, and we don’t talk about our future to others much. Some graduate school friends are going to Vancouver Island this summer to start a commune. They sense our paths are forking, but no one’s asked us point blank what we’re going to do next year, and we haven’t told them our plans are definite now. The mountain range that dances across the horizon at sunset in the Huerfano burns in our memory. The people building their houses at Libre can teach us a lot. They have their flaws, like everyone else, but they also have the courage to be the vanguard. They’ve grown to match their landscape. They are mountain men and women, artists, and free. We want to be like them. Frankly, we don’t think our lovable, inexperienced, goofy, intellectual friends in Buffalo will last long in the Canadian woods.

Tonight many of these friends are sprawled in the living room of our second-floor apartment. It’s surprisingly warm, and the doors are open onto the balcony overlooking Arlington Park. The elms haven’t leafed out yet; in fact, most of them are dying from Dutch elm disease, but their large, graceful skeletons are silhouetted in the streetlights. Rick’s gotten some MDA from the army. Actually, Rick got it from someone who got it from someone who supposedly got it from the army—naturally, Rick keeps his sources secret. He says the army developed MDA to dose hostile populations, to make them more docile and manageable. He’s taken some before and says it’s great. The Band is playing on my KLH, and we’re all smiling at one another, nodding to “Across the Great Divide”: “Across the Great Divide, / Just grab your hat and take that ride, / Get yourself a bride, / And bring your children down to the riverside …”

Kevin lights a pipe of hash, sucks on it rapidly to get it started, and hands it to David. Kevin’s in graduate English with me, but he’s a little older. He was a monk for a while, but he’s switched his sacraments. His pale blond hair is perfectly trimmed, chin length, and naturally wavy, sort of like a forties starlet’s hairdo. His beard and mustache are trimmed neatly too, and his large blue eyes seem even larger through thick, rimless glasses. Do monks still shave their heads? I can’t see Kevin without his hair.

Friends gather at our house—it’s spacious, with hardwood floors, working fireplaces, and balconies on the park. Kevin, who lives in the apartment downstairs, says this was the actress Katharine Cornell’s childhood home, now split up into apartments any graduate student would die for. Friends also gather here because David and I are one of the few long-term couples in the group. We’re Peter and Wendy, and this is our gang. Because we haven’t told them yet that we’re not going to Canada, this evening’s bittersweet. David’s and my eyes meet occasionally as they chatter, and I just can’t believe it—we’re going to join Libre and build a home nine thousand two hundred feet up Greenhorn Mountain and live there differently and forever. We’ll be psychic pioneers.

On paper, we don’t seem prepared for this choice, no more ready to make the change than our friends heading for Vancouver. I graduated from Vassar in 1968, and this is my second year of a teaching fellowship in the English Ph.D. program at SUNY Buffalo, where I came to be with David. He graduated from Yale in 1968, too, and his Yale professor asked him to come with him to help start the new American Studies program up here. This job has the invaluable perk of a graduate school deferment from the draft and Vietnam, at least for a while.

The fact is, neither David nor I have ever built a bookcase before, or anything else for that matter. I suppose David took shop in high school, but I’ve never seen him with a tool in his hand in the six years I’ve known him. We’ve lived the life of the mind in suburbs and cities all our lives. This lack of practical skills doesn’t stop us from wanting to head for Libre to build a house by hand, without electricity, on a frequently impassable road halfway up a mountain. We’re young and strong, and we can do anything.

At Buffalo I’m studying Blake and teaching journal writing to most of the freshman football team. English is required freshman year, and journal writing is the athletes’ course of choice. I’m slim and small and have long, straight blond hair. My students are big and built; each one’s neck looks bigger than my waist. I urge them to talk about their feelings while we read Anaïs Nin, who, even in her delusions of grandeur, may not have expected an audience of eighteen-year-old football players from places like North Tonawanda, New York. I try to discuss Vietnam with them in class—many students have brothers or friends there—but they look down at their desks and don’t want to talk about it, maybe because they think I’m crazy or stupid or worse. I don’t have David’s charisma or his leadership abilities. But I’m their teacher, and they flirt with me, awkwardly and politely, humoring me as best they can, confessing more and more in their journal notebooks as the semester progresses. Meanwhile, their uncles and fathers sit in bars along Delaware Avenue with other steelworkers and pray that some hippie will be stupid enough to come in and ask for directions or a beer.

David’s across the living room, messing with his guitar and amplifier. He’s tall, dark, muscular, and lean. He has high cheekbones, pale skin, wild dark eyes, and black hair and mustache. One grandfather was a North Carolina Cherokee. David is handsome, and his eyes burn. He looks like a cross between Omar Sharif and Henry Fonda with a soupçon of Tonto thrown in. He has the look that visionaries, poets, and some outlaws have—one eye’s focused a little further into the future than the other. This may be why he pays a little less attention to the present than I do. In the new American Studies program at Buffalo last year, he taught a class called “The Outsider.” This year it’s titled “FREAK.” On his reading list is Hunter Thompson’s Hell’s Angels, Kerouac’s On the Road, Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Ginsberg’s Howl, The Stranger and all the rest of Kafka, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. His course is so popular that, even though it’s full, many unenrolled students drop in to participate. The large attendance is due to the exciting revolutionary thoughts and insights expressed there, but also because lots of students smoke joints together throughout the class.

This winter, even David’s class was canceled when SUNY Buffalo was shut down because of student revolt. The campus ROTC building was burned down one night, and its records were destroyed. Unemployed steelworkers drove through the campus shooting at longhaired hippie-looking students. It was a cloudy, grim winter. While we were away in Colorado, our two cats, Yin and Yang, died from some no doubt environmentally caused disease. JB, a close friend, checked into a mental hospital and detox program last month, not long after he’d organized the clandestine midnight brigade who drove around Buffalo stenciling WAR under STOP on all the stop signs. We didn’t see the sun once in January. Gary Snyder—the Japhy Ryder of Kerouac’s Dharma Bums—visited, and one long, dark winter night we had a party and danced so exuberantly that the hardwood floor of our apartment shook. Kevin lives downstairs, so no one complained. Snyder knew of Libre and the Huerfano because his friend Nanao, a Japanese poet, was visiting there. We showed Snyder my pictures of Libre and New Buffalo and Morning Star Commune, and he asked, “Why don’t you go there?” We couldn’t answer. Baba Ram Dass, aka Richard Alpert, Mr. LSD, came through Buffalo, too, dressed in white robes now, drug free and high from two years in India with his guru. We told him about Libre, and he said, “Follow your heart!” It’s silly, but when he said that, it felt so simple, so profound.

Beyond the local indications of doom is the tragic, revolting big picture. Che, Malcolm X, Martin, and Bobby are dead. In February, the Weathermen blew up a Bank of America out West. In March, three Weathermen blew themselves up in the East, making a bomb with some sticks of dynamite and an alarm clock in a Greenwich Village brownstone that one of Edith Wharton’s eligible bachelors might have lived in late in the previous century. The three were about our age. Nixon expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia, and last fall at a demonstration at the Pentagon we were teargassed. We were in the front, and one soldier must not have liked the way David looked at him. Or maybe it was the large black and white silk pirate flag I’d made for David to carry. When the order came to gas the crowd, the soldier aimed a canister at David’s head, and it knocked him down. The neighboring strangers didn’t panic and trample over him. Instead, they helped David’s brother Doug and me pick David up. Gasping and choking on gas, we held him up and helped him run. He didn’t drop the flag. It’s on our apartment wall, by the poster for Cream at Fillmore East.

Bob the Rake, who’s sharing a large maroon Naugahyde chair with me, passes a pipe. I take a light puff and smile at him. He’s broken five women’s hearts in the past three months—and those are only the ones I’ve heard about. He’s got dark brown bedroom eyes, thick eyelashes, wavy brown hair. He’s not killingly handsome, a bit stocky even, but he’s got a way with the women, and a libido turbocharged by a Catholic boys’ school education. The stereo’s off, and David’s tuning up his electric guitar. Buddy, back from Chicago, where he’s been clerking for William Kunstler on the trial of the Chicago Seven, is picking languidly on a bass. Suddenly, I’m overwhelmed with love for everyone in the room. Even Bob the Rake seems harmless and endearing. Joanne, hopelessly in love with Bob, gets up, flicks a cigarette over the balcony, and closes the balcony doors, either because it’s getting cold, because she’s worried about the electric guitars and the neighbors, or because Bob is driving her crazy.

I stare down at the frayed oriental rug my parents gave me to bring up here. It wasn’t new when I crawled on it as a baby. My parents are angry that David and I are living together in sin. It’s my mother who’s most angry, but my father’s going along with her. I’ve visited over the last two years, but they don’t allow David in the house and refuse to speak his name. Maybe it’s the MDA that makes me feel a surge of love for them, too, along with love for all the people in the room, and the conviction swells up in me that it will all work out, though I’m not sure of the details. If I were a hostile native, I’d drop my Molotov cocktail now.

David plays Leadbelly’s “Bourgeois Blues,” then a Woody Guthrie tune, “Deportee,” then Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Great Balls of fire.” His soft tenor voice is clear and slightly southern, no matter what he sings. I’ve heard him practice these songs late into the night. Now he starts “Shop Around,” the old Smokey Robinson favorite which he’s been playing a lot lately. Everyone’s swaying, and Buddy’s picking up the bass line surprisingly well. The lights are low, the large candles dripping and flickering.

When I became of age, my mama called me to her side,

She said, “Son, You’re growing up now,

Pretty soon you’ll take a bride,” …

She said, “Son, You’re growing up now,

Pretty soon you’ll take a bride,” …

David doesn’t try to sound like Smokey Robinson. His version is true to who he is, and slightly Appalachian. I feel lucky to be with a person who’s so intelligent, such a creative thinker, so handsome and hip. I also feel Bob’s hand on my back under my Mexican blouse, and I jump a little, wondering when he put it there, but then he’s just been stroking my lower back softly, and it feels good. Not sexual, just good. I smile at David across the room. He looks at me briefly, then looks down at his fingers on the frets.

“This feels so good. You’ve always been so cool and distant! You’re such a weird mix of reserve and passion, I’ve always wanted to do this,” Bob whispers as David plays a bridge between verses, and Glint gives a Texas good ol’ boy hoot of approval. Candlelight glints on the thick lenses of Glint’s wire-rimmed glasses, and the wire arms disappear into his large, muttonchop sideburns. I should say to Bob that I’m so cool and distant because I’m in love with David and committed to him. Also, I’m friends with Joanne, who has loved Bob forever, and unlike some people, I believe in being faithful. But I’m feeling too good to be snide, and David looks up from his guitar meaningfully with his dark, indigenous eyes. I smile back, pretty sure neither he nor anyone else has noticed Bob’s arm halfway up my back. Joanne would notice if it weren’t so dark.

David sings the chorus in a high falsetto.

“Try to get yourself a bargain son,

Don’t be sold on the very first one

Pretty girls come a dime a dozen,

Try to find one who’s gonna give you good lovin’ …”

Don’t be sold on the very first one

Pretty girls come a dime a dozen,

Try to find one who’s gonna give you good lovin’ …”

He sings and plays with more feeling and flourish than ever. Bob runs his fingers over my back lightly, and I sway a little, to avoid his fingers getting more intimate, and because the music sounds so good I can’t sit still. Then David strums his guitar loudly and pauses. Everyone stops swaying and looks up. Glint spills his beer.

“Roberta Price”—David strums dramatically—”Will you marry me?” Bob’s hand freezes. Glint’s mopping up beer with his sweater and grinning. Everyone’s smiling at me, and I smile across the room at David. My face flushes with embarrassment and MDA. I want to get married, but it occurs to me (inappropriately, it seems) that he must be very confident of the answer to ask me in a crowd. Why shouldn’t he be confident? I think irritably. But, almost as soon as I think that, I wonder if he’s asked me like this because it would really be very hard for me to say no in this situation. Why am I having such foolish thoughts? It must be the wine, the hash, or the MDA. I’ve been sure that I wanted to marry David all the time he’s hesitated and said marriage is too conventional. Have I been so sure because he’s been so doubtful?

Everybody’s staring. It’s been forever since the last guitar chord reverberated in the dark, sweet, smoky air of the apartment. I’m looking at David, and then I remember Bob’s hand on my back and wonder if anybody’s noticed. Bob’s lowered his hand a little and has stopped running his fingers over my skin, so at least my goose bumps are deflating. I look down, blush more, and then I say, “YES!” Glint hoots again, and lurches away to the kitchen in his worn cowboy boots for something to clean up the beer, and Bob puts the arm that was under my blouse around me.

“Pretty girls come a dime a dozen,

Try to find one who’s gonna give you good lovin’,

Before you take a girl and say I do now,

Make sure she’s in love with you now,”

My momma told me, “You betta shop around.”

Try to find one who’s gonna give you good lovin’,

Before you take a girl and say I do now,

Make sure she’s in love with you now,”

My momma told me, “You betta shop around.”

David sings on. Bob looks sideways at me, thick, dark eyelashes at half-mast. He smiles and whispers, “April Fool!”

I get up and cross the room to David, threading through our friends on the floor. I really don’t think Bob was kidding.

2 : May Day

May 7, 1970

Five weeks later, on the way to tell New Haven friends about our wedding, we loop south to White Plains to tell my parents. I call from a gas station on the Merritt Parkway, and Mom sounds a little surprised, but she doesn’t say David can’t come to the house. Maybe she senses we’ve got news. We drive up the hill in our 1947 Chrysler Windsor coupe that we bought in Barstow, California, last July, after our Corvair camper died a miserable death in the desert outside Needles. When we found the Chrysler in the first used car lot coming into Barstow, we opened the glove box and found the owner’s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Prologue, November 2003

- 1 Shop Around, April 1, 1970, 5

- 2 May Day, May 7, 1970

- 3 The Wedding Gang, May 23, 1970

- 4 Searching, June 1970

- 5 Libre, June 1969

- 6 The Way West, June 2, 1970

- 7 Libre Again, June 4, 1970

- 8 Come Together, June 5, 1970

- 9 You Can Be in My Dream If I Can Be in Yours, June 5, 1970

- 10 Up on the Ridge, June 24, 1970

- 11 Food Stamps, July 1, 1970

- 12 Water, Cool Water, July 4, 1970

- 13 The Time Capsule, August 5, 1970

- 14 Visitors, September 2, 1970

- 15 Heart Failure, September 15, 1970

- 16 The Libra Birthday Party, October 8, 1970

- 17 School Days, October 12, 1970

- 18 Pearl Harbor Day, December 7, 1970

- 19 The Physical, January 11, 1971

- 20 Sinbad, February 1971

- 21 Miami, March 15, 1971

- 22 Here Comes the Sun, April 1, 1971

- 23 The Nature of Time, May 1, 1971

- 24 Lia, May 15, 1971

- 25 Change in Seasons, August 15, 1971

- 26 Gathering Together, November 1971

- 27 Consciousness Raising, April 1, 1972

- 28 Easter, April 8, 1972

- 29 Brotherly Love, June 15, 1972

- 30 Woodstock Revisited, August 10, 1972

- 31 Julep, May 1973

- 32 The Peach Run, August 12, 1973

- 33 Mr. Wagley’s Peaches, August 18, 1973

- 34 Homecoming, August 1973

- 35 Cousin Carlene, September 1973

- 36 The Red Rocks, October 1973

- 37 Horse Dreams, December 24, 1973

- 38 Biting the Bullet, June 1974

- 39 Tricky Dick, August 8, 1974

- 40 Rufus, September 1974

- 41 Me and Bobby McGee, November—December 1974

- 42 Nick, February 14, 1975

- 43 Christine, March 1975

- 44 The Bionic Dog, April 1975

- 45 The Roundup, September 1975

- 46 Aunt Mabel and the Owl, August 1976

- 47 Donuts, September 1976

- 48 More Big Birds, October 1976

- 49 The Deerskin and the Dobie Pad, June 1977

- 50 The King Is Dead, August 1977

- 51 Beatniks in the Huerfano, August 1977

- 52 Ram Dass and Holy Faith, September 1977

- Postlogue, November 2004

- Author’s Note and Acknowledgments

- Back Cover