![]()

1

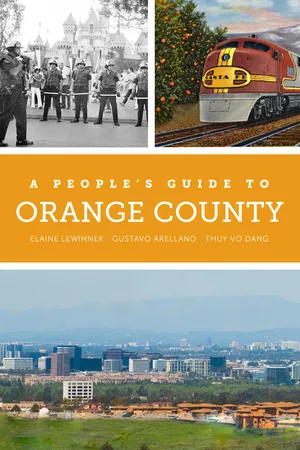

Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana

Introduction

IN 1769, WHEN THE GASPAR DE PORTOLÁ expedition crossed what they ended up calling the Santa Ana River and camped near what would become present-day Anaheim, the Spanish invaders recorded groves of willows, alders, and sycamore trees, a wide expanse of rich soil, and a populous Native village whose name they did not bother to record. Fifty-two of the Indigenous people from that village visited the explorers, generously offering antelopes, hares, and seeds. Today, this river crossing is a treeless, cemented expanse where homeless people camp. A great deal has happened between those first written observations of this region and today, and that is the subject of this chapter.

The Acjachemem and Tongva called this river Wanaawna, meaning river-winding, and shared the territory north of the river. The river itself moved before being contained in concrete in the twentieth century, but it was a dividing line between giant Spanish land tracts, continuing to separate ranchos during the Mexican period. After US conquest, the cities built on this fertile floodplain—Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana—were the first three cities incorporated in Orange County, occupying areas near what had been the Indigenous villages of Hotuukgna, Pajbenga, and Totabit. The US cities competed for access to the river’s water (see Site 4.8, Yorba Regional Park, in the mountains upstream from here). In 1889, these cities also competed to name the newly formed county after themselves, proposing the names Anaheim County or Santa Ana County, each trying to centralize political and economic power within its respective locale. Since neither city could convince the other, they eventually compromised with the name Orange County. Santa Ana won the battle for the seat of county government, while Anaheim eventually housed important corporations and professional sports franchises. Together, Anaheim and Santa Ana remain the two largest cities in this county. In 2015, Anaheim, Santa Ana, and Orange held one-quarter of the population of Orange County. These central cities are simultaneously seats of power and sites of rebellion.

This space has long had contested diversity. A German American wine-growing cooperative founded Anaheim in 1857, naming it with a Spanish-German hybrid portmanteau word meaning “Home by the Santa Ana River.” Chinese workers cultivated grapes there until 1884, when “Anaheim disease” destroyed the town’s monocrop grapes and the region’s agriculture shifted to more diversity, including walnuts, sugar beets, lemons, oranges, berries, lima beans, and livestock. In the 1920s, when the town’s leaders agreed with many German Americans who did not support Prohibition, an opposing group led by the Ku Klux Klan won election, dominating Anaheim politics so thoroughly that Anaheim’s sidewalks were inscribed with “K.I.G.Y.,” an acronym for “Klansman I Greet You.”

Nearby cities were not immune to such white supremacy and such deep contradictions. The Anglo founders of Santa Ana included Civil War veterans who had fought for the Confederacy as well as radical free-love socialists from the Oneida colony of upstate New York who muted their radicalism here. Santa Ana was incorporated in 1886 when it was the white-dominated urban center of Orange County, but a twelve-block area known as “Little Texas” developed in the 1920s along Bristol Street near Fourth, around the home of Willis Duffy, the Second Baptist Church, and the AME Church, in a Mexican American neighborhood one mile from downtown. Little Texas housed African American migrants from across the Southwest, not just Texas. Until the 1940s, the African American community of Santa Ana had to carry lunch boxes when they left their homes because no Santa Ana restaurant would serve them a sit-down meal. No mortuary would embalm them either, and most movie theaters required them to sit only in the balconies. They persisted and thrived anyway.

Santa Ana also held Latinx barrios, especially in the Logan, Santa Nita, and Delhi neighborhoods. A commercial stretch of Fourth Street east of Main was so dominated by Latinx businesses that by 1930 it became known as “Calle Cuatro.” In 1943, when military personnel across Los Angeles County infamously attacked Latino, African American, and Filipino zoot suiters, more than three hundred servicemen from Orange County’s El Toro Marine Base also tried to assault zooters on Calle Cuatro, believing the Santa Ana Register’s sensational assertions that pachucos were anti-American criminals. While zoot-suited victims were arrested in Los Angeles, it was four sailors and a marine who faced arrests in diverse Santa Ana.

After World War II, seeking to disperse population in the face of atomic threats, California’s Division of Highways extended Los Angeles’s freeways southward to Orange County, selecting a route that cemented the role of Anaheim, Orange, and Santa Ana as central hubs for the Southern California region. The freeways brought new suburban residents and new industries, especially in defense manufacturing. In 1954, the Long Beach Independent-Press-Telegram joked about the region that had debated naming itself Anaheim County or Santa Ana County: “Pretty soon it will be Orange County no longer. It will be Tract County.”

In 1955, those freeways also attracted Walt Disney to Anaheim. Rejecting the heterogeneous, mixed-class, sexually adventurous “carny” atmosphere of earlier urban amusement parks, Disney deliberately sought out the suburban and mostly white space of 1950s Anaheim in order to build a carefully designed landscape promoting his idealized nostalgia for small-town America, sold to nuclear families in a privatized landscape of predictable leisure.

Like Disney, the city of Orange tries to maintain a Mayberry appearance that implicitly promotes conservative politics. Its Old Towne district, complete with a quaint downtown circle, is the largest National Register Historic District in California. It was also the home base for Radio White, one of the first white-power online radio stations in the United States. The neo-Nazi scene here formed Wade Michael Page, who killed six people at a Sikh temple in Wisconsin in 2011. Also within Old Towne Orange is Chapman University, which has bronze busts of libertarian icons like Milton Friedman and Clarence Thomas but whose school of education teaches future teachers the radical pedagogy of Paolo Freire.

In the 1950s, white residents began moving out of Santa Ana’s core. Until fair housing laws took effect after 1970, African Americans worked throughout Orange County but largely lived in Santa Ana’s Little Texas neighborhood, as well as two smaller two-block neighborhoods in Fullerton and Placentia. In addition to the vibrant community in Little Texas, along Calle Cuatro travel agencies, quinceañera and bridal shops, beer bars, discotecas, restaurants, jewelry stores, and El Cine Yost movie theater catered to Latinx customers. With an influx of Latinx people after the immigration reform of 1965, by the 1980s Santa Ana had as many Latinx people (45 percent) as white people. While the Cold War–era military dominance of Orange County encouraged conservative politics, it also brought global Cold War refugees, so these three cities contain growing neighborhoods of Arab Americans alongside communities of Cambodians, Guatemalans, Filipinos, Salvadorans, Samoans, Romanians, and Vietnamese, making a former center of conservatism into a contemporary center of rapidly changing demographics and a battleground for national debates about immigration.

The old guard in each city has not taken kindly to increasing diversity. In Orange, council members have sought to ban day laborers from city limits, welcomed gang injunctions placed on the city’s barrios, and fought a request by activists to shift elections from an at-large system to one that would split Orange into districts to encourage more diverse political representation. Anaheim also fought district elections until an ACLU lawsuit forced them to accept that arrangement in 2016. Orange finally switched over to district elections in 2020 after activists sued under the California Voting Rights Act.

In Santa Ana Cemetery in 2004, the Sons of Confederate Veterans erected a domineering nine-foot granite pillar inscribed with the names of Confederate rebels—many of whom had never entered California—along with the message, “To honor the sacred ...