![]()

CHAPTER 1

Abenaa Adiiya

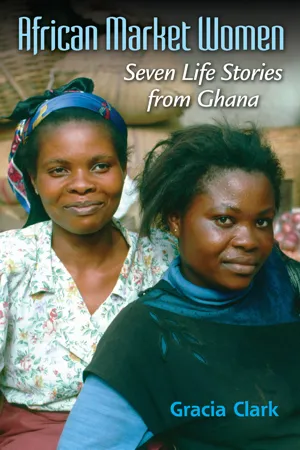

Portrait: An Adventurer on the Road

Our work, it’s like a lottery. If God helps

you, then you go out and you win.

Abenaa Adiiya was a short, robust, businesslike woman in early middle age. She cheerfully kept up a grueling weekly schedule of predawn departures on buying trips, maintaining several distinct travel patterns in different seasons. In social conversation, as in this narrative, she mainly talked about profits and losses on particular routes, with a rueful laugh for the stories of bad luck. The relatively high capital required for her tomato wholesaling business put her into the top level of traders in perishable foodstuffs, but this financial capacity was stretched at times. She considered herself tough and was proud of it, with confidence in her own strength and judgment.

Her square, closed face and stocky build rarely showed much sentiment. Her eyes became wistful only when she talked off the record about her early, unwilling marriage. When I asked her to record her life history, she was also matter-of-fact. “Let’s do it right now, I’m ready,” she answered. By the time we reached my house, she had her piece to say worked out, short and direct. It was hard to get her to elaborate. “Didn’t you understand it? I said it all,” she responded. She had no qualms about having her name and picture used: why, she asked?

Yet she would do anything for those she loved. She never begrudged taking time off for her relatives’ illnesses or funerals. She was brusque with the several small grandchildren who lived with her, yet she admitted they live with her partly because otherwise she would live alone. She fiercely vowed to educate them, since she had missed that chance with her children. Her regrets and ambitions for her children and grandchildren are expressed in terms of the core material aspiration for many Asante: to build a house to leave them. Her dim view of current economic prospects for herself and her country can be measured by her single-minded aim to get them out of Ghana, in order to have a chance at achieving this basic security.

I had stayed with her in Bolgatanga, in the far Upper Region, for several weeks in 1979, so we knew each other well and even shared a few secrets. On Sundays, I often found her at home resting after attending an early church service in the neighborhood. In her old clothes, she liked to watch old U.S. and Chinese children’s serials on television. When I later came in my car, she would often suggest going to visit someone—the retired leader of her tomato buying group in Bolgatanga, or her elderly unmarried aunt in the suburbs. If she had a weekday off, she would get dressed and go down to the wholesale yard to discuss prices with her colleagues.

Her story is full of business details; she revels in prices and credit strategies. Gradually, I understood how this steady stream of transactions inscribes her life’s events, emotions, and wisdom, just as it enabled her to realize them over the course of her life. Her pride as a young wife, her ambivalence about modernization and city life, even her faith in God are all documented and inflected by the prices and profits of the day. The perishability of her tomatoes makes her very aware of risk, and she discusses the various hazards of supply volatility, unreliable transport, and credit default.

She talks more about government policies than many traders, and considers them influential on market conditions. At that time, the official annual budget still set the sale price of gasoline and the buying price of cocoa despite international pressure to deregulate. She understands that increased competition from new traders lowers her income, but does not blame the massive public-sector layoffs under the SAP. Instead, she blames population growth, the result of more children being born and surviving. Before all, she finds comfort in the thought that her fortunes and misfortunes are ultimately part of God’s plan.

The year she reviewed her transcripts, this confidence was severely shaken. The theft of her whole trading capital, while she rested at the end of a delivery run, had left her stunned and financially unable to continue traveling as before. Even buying a secondhand freezer to sell ice water and popsicles was beyond her means. Then a fire in the market destroyed the major remaining family asset, her aunt’s stall. After trading in tomatoes all her life, she was now scrambling to imagine what kind of work she could still do to support herself, let alone to reach the goals she had set for her family.

Story: Patience and Pleading

At first, the world was good, and as for me, I know what I know, in my own mind. What I mean is, the Bible says that this is not true, and if things are good now, times will come that are bad. First of all, I know that my mind tells me that the Bible said that when the world is coming to an end, conditions will be hard. That’s how I know that very time has come.

When you first came, and you and I used to play around, about four years ago—

MA: About ten years.

About ten years ago—

GC: It was about fourteen years ago.

Well, at that time fourteen years ago, when you and I were going to Bolga, how much did the car even charge us? Five hundred cedis. We boarded the State Transport bus, and it was five hundred. Today, the fare to Bolga is six thousand cedis. I mean, the world is going up [kɔ so]. Everything is going up and finally, too, the people are too many. If we are too many, then problems will set in with everything. At first, in trading, the people who were trading were not many, only a few people. The more we get, the more everyone struggles to get into trading. Nowadays, for example, look at this handbag I am holding now. If I were selling it and not many people came around, I could not raise the price very high. Wahu? If you come by, and Akua comes by, and someone else also comes by, I know that someone will surely buy it, and this lets the price go up.

OK, it is partly due to the petrol, too. I mean, what makes things get expensive is petrol. At first, when I was starting to travel, the car charged me 2500 cedis. Then they raised the price of petrol, and when they raised the price, they raised the fare to 3000. Just the other day it went up again, and now they charge 3500. That’s why I know very well that if they change the budget and raise the petrol price again, they will raise the fare again to 4000. These days, the very high prices of things are really due to petrol. I mean, if they raise the price of petrol, it affects everything. I mean, people have to take a car. If you sell things, you need to take a car, you see? That’s why foodstuffs and everything, cloth or clothing, everything is so expensive. Everything really depends on petrol, really. That’s why I say the rising price of petrol has caused all of the problems in Ghana today. A person cannot pick up this chair and, with your own strength, walk with it for half a mile. You cannot carry this table. Whatever happens, you have to take a car. Wahu?

A few days ago I went to buy yams at Ejura. When we first went to buy, for every hundred yams the car charged two thousand cedis. Today, if you go to buy a hundred, they charge five thousand. Just like that, they raised it three thousand cedis. That’s why, if at first I sold the yams for two hundred each, now I cannot sell them for two hundred. I have to sell them for about three hundred each. So as for the hard times, really it is because they are raising the price of petrol so very fast. Petrol makes everything hard. Today food is also hard. All of it ends up with this petrol business.

In the old days, as a poor person, if you had even five hundred cedis to take to market, you could eat. Today, take me and these children of mine. Now, even if I haven’t bought much I have spent eight hundred cedis, only for the staples, before you have gone to look for meat. And sister, the work you do, if you work for one day, how much will you earn? How much will you get? That’s why, as for me, the thing I know is that it all, mostly, is because of petrol. Petrol has made the prices of things get very, very high, and as soon as they raise it, it affects everything. OK.

I mean, they say they have raised the price of cocoa, and then the prices of things have got very expensive. As for cocoa, I don’t have any myself; you don’t have any. None at all, none of my relatives have ever planted any cocoa at all. But if they raise the price of cocoa, and the prices of all other goods go up, it affects all of us. So, the things that have changed in this world, they are due to cocoa and petrol, the two of them. That’s what is on my mind. If she has anything to ask about it, she can ask so that I can explain.

GC: When you were young, was it this hard?

No, not at all. At the time I was a child, when I grew up enough to be buying cloth, I paid three hundred cedis. I bought cloth for three hundred. I gave birth, we named my child, they gave me six hundred. With the six hundred, my mother bought three cloths for three hundred each. Even the really expensive cloth she bought was four hundred cedis. Wahu? But today, if you wear European cloth, if you are buying it and you don’t have fifty or fifty-five thousand cedis, you won’t be buying any. Fifty-five or sixty, you see? In the past, that kind of cloth we bought for five hundred cedis. Today, funeral cloth is ten thousand, and plain funeral cloth used to be cheap, but today it is ten. So between the old days and these days, there is no comparison.

When I had just married, at first [repeats this three times] my husband gave me five shillings. Five shillings a day I took to do the marketing. Only five shillings, and I did a lot of shopping. Later, when he had brought his nephew to live with us, so that his nephew could learn car repair, then he was giving me six shillings. That six shillings, it was really something! I mean, times changed and he gave me ten shillings, and finally he was giving me twelve. I mean, with that twelve shillings I was quite a rich woman. I was only a young girl, and I had senior Magazine workers to look after.1 I was really wealthy. But sister, the way I am living now, when I go to market, I can take three or four thousand, and it is not enough for my shopping. So I mean, in time, everything is going up. As time passes, everything goes up.

People are also getting too many. At first, people were not so many at all, like today.

GC: Why were people not as many as today?

OK, like at first, when you had given birth, I mean, like, today we are giving birth more, in the end. My mother was an only child, now she has had seven children. Now, I also, my own flesh and blood, they are ten. Myself I had three, and my children had five. It adds up to how many? Isn’t it eight? We are growing. I mean, people are really too many. So, because we are so many, everything will go up. Wahu?

Comparing today to before, then a lot of people did not try to come live in a big town, also. Today, all the children who finish school in a village say, “I am going to Kumasi, I am going to Accra.” Instead, if a child finished then, he would not decide to go anywhere. He would stay right there with his mother. Today too, everyone wants to come to a big town so he can be modern.2 And when modernization gets really too much, things will also get expensive. Right now, modernization is rising fast. People are too modern.

MA: Now, preacher, tell about your own life.

As for my own life, oh, as for my own life, sister, it is also hard. Only because of God, I mean, right now, I have this work I am doing. OK, my husband is a driver, if he goes on the road, but recently he has just stayed home. For about two years, he has had no work.

GC: He doesn’t have a car?

No, he has no car. I mean, because it’s all on me, I get so tired. If I go and earn something, and I come back, little by little, we make it by ourselves, little by little. So if he does earn something, if he is someone who works for someone, it isn’t like the one who works for himself. So right now, he goes and comes and if he earns two thousand and, agya, if he gives it to me, I take it. The day that he doesn’t earn anything, too, I just hang on.

So it’s just like that with me, in this work that I do, that’s the thing that doesn’t let me get ahead, you see. I mean, the food money is too much. The people living with me now, we are eleven. As a nursing mother3 in Kumasi for these eleve...