![]()

The Making of a Railroader

1 NOT UNTIL AGE twenty-three did I even imagine working for a railroad. I was born in 1942 in Sacramento, California. My dad, Ward Krebs, was a banker, working for American Trust Company, which later became Wells Fargo. He was the great-grandson of people who came west by wagon train during the Gold Rush and settled in Hangtown, also called Old Dry Diggings, which is the present town of Placerville, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. My mother was Eleanor Duncan Krebs, whose relatives hailed from Scotland and came to California by way of Canada. I was their only child.

Railroading was absolutely, positively not in my blood. Try as I might, it’s hard to think of any interest in or experiences with railroads during my upbringing. Like all boys in that era, I had a Lionel train set my dad and I would set up at Christmas. And I recall going to Sacramento to see my parents board Western Pacific’s California Zephyr streamliner for a banking convention in New York City. Maybe I had a short train ride or two as a kid. If I did, it wasn’t memorable.

But there was one connection I should note between my childhood and the life I would later lead, because I hated it. When I was in third grade, my father was transferred from Sacramento to North Sacramento to run a branch of American Trust. We moved to be close to that branch. I had to forge a whole new set of friends. Then his employer bought a bank in Woodland, 20 miles to the west, and sent my dad to run it. Again, we moved, and again, new friends. For my dad, running that branch bank may have been the happiest time in his life. But it wasn’t mine. When I was in seventh grade, dad was transferred back to Sacramento. Another move, another loss of friends, another struggle to make new friends. I vowed I would never subject my children to the stresses of being uprooted every few years. But that’s exactly what happened.

I loved Northern California. As far as I was concerned, the sun rose and set on San Francisco. Throughout my youth and well into adulthood, that great big beautiful city or somewhere nearby was where I wanted to spend my life. So it was natural that I would attend Stanford University in Palo Alto, my dad’s alma mater. By then my parents lived in Hillsborough, south of San Francisco on the peninsula, and I enjoyed bringing my fraternity brothers home on Sundays, where we would enjoy a good home-cooked meal while my mother did my laundry.

Stanford didn’t have a business major, which was probably just as well. Instead, I majored in political science. I figured that my undergraduate years should be a liberal arts education, so I took economics, history, language, and political science courses. I also went to Stanford’s campus in Florence, Italy, for two-thirds of my sophomore year. That experience spawned a lifelong love of Italy and of art.

When I graduated in 1964, I headed straight for business school. Since I had already been to Stanford, I chose Harvard and was accepted. Back then, the Harvard Graduate School of Business admitted quite a few students right out of college. It was a mistake, for me at least, and now several years of experience in the real world is pretty much a requirement for admission. I treated my two years in Cambridge as if it was a continuation of my undergraduate experience. Our second year, my three roommates and I cut classes on Wednesdays and Thursdays to ski in Killington, Vermont. One roommate caused a stir when he came to class to hear a lecture just before the semester ended—his first appearance since registration. And he aced his final.

One course had an especially lasting impact on me: Human Behavior in Organizations. It focused on such topics as what you do when you run an assembly line and how you get people to work together so the line runs smoothly. I also acquired a financial background and learned to understand balance sheets and earnings statements. Through case studies I was exposed to concepts of management control—as applied to railroads this would mean what measurements allow you to understand whether a yard is functioning smoothly.

In early 1966, in my last semester, I started looking for a job. As I said, my dad was a banker, and I wanted to be a banker, too. When I was at Stanford, Dad had gotten me a job during summers at Crocker National Bank in San Francisco. But he counseled me that if I wanted to follow in his footsteps, I should go to New York, because New York City was the global capital of banking. And Dad said the best bank in the world was Morgan Guaranty Trust Company of New York, which later became J. P. Morgan, and several mergers later is JPMorgan Chase.

Each spring Morgan Guaranty hired maybe a dozen Harvard Business School graduates, and I was invited to go to New York for interviews. I walked into the bank’s main office on Wall Street and I swear the green carpet was two inches thick. The people I met sat at big rolltop desks and had their shoes shined while we talked. Everyone seemed young and ambitious and competitive. I thought, this is crazy. Look at all these people trying to claw their way to the top, and in New York City, which I don’t particularly like anyway.

Southern Pacific Company, holding company of SP Transportation, recruited at Harvard too. SP sent Dean Johnson, a senior manager of the computer department, as its representative. Southern Pacific was just starting to implement TOPS, or the Total Operations Processing System, which was an early IBM computer-based accounting and control system. I thought Johnson was looking primarily for people to work in the computer department. Harvard Business School seemed to me a strange place to be seeking computer experience, and it certainly wasn’t what I had in mind.

But the important thing to me was that Southern Pacific was based in San Francisco. So I signed up to meet Johnson. I told him I wasn’t terribly interested in programming. I asked, “How about operations or something like that?” This was what really interested me, little as I knew about it at that time. I always thought the operating side makes any company, and especially a railroad, succeed or fail. I figured the people who someday would run the railroad would come from operations rather than what we now know as information technology. Johnson was probably surprised that I preferred operations but arranged for me to come to San Francisco for interviews.

Southern Pacific’s grand general office building stood at the foot of Market Street, next to the Embarcadero and adjacent to the financial district. The eleven-story high-ceilinged red brick structure was built to replace offices destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. It stood in the shape of a U, because SP originally planned for the building to double as its downtown passenger station. But during the Depression the adjacent land was sold to the US government for a postal building, and generations of commuter-train riders, including me, have had to trudge an extra half a mile from Third and Townsend streets to reach their offices.

I walked into 65 Market Street (later expanded with office towers and relabeled 1 Market Plaza), and the contrast with Morgan Guaranty Trust on the other side of the country could not have been more vivid. Everyone at Southern Pacific looked to be sixty-five years old, at least to my young eyes. I met with second-level people, not the chairman (Donald J. Russell), the president (Ben Biaggini), or the vice presidents of operations and traffic (Bill Lamprecht and Bill Peoples). Later, I also looked at the other big companies in San Francisco, including Standard Oil of California (Chevron), Crown Zellerbach, and FMC Corporation.

I’m sure that what got me a job offer from SP, besides the fact that nobody else wanted to work for railroads, was that I had gone to Stanford and had a Harvard MBA. The offer was to enter the railroad’s two-year management-training program at a salary of $775 a month. Morgan Guaranty made me an offer as well. The deciding factor became location. I had no love or appreciation for railroads, but SP was in San Francisco (good) and Morgan was in New York (not so good). I could have sat at one of those rolltop desks getting my shoes shined every morning with all the other recent HBS graduates. In stark contrast, at Southern Pacific the managers all looked ready to retire. Southern Pacific represented opportunity, and why not reach for that opportunity? So I said thank you but no to Morgan Guaranty and in June 1966 went to work for Southern Pacific Transportation, the railroad subsidiary of Southern Pacific Company.

My roommates at Harvard were aghast when I informed them I was going to work for SP. They could not believe the magnitude of my mistake. One of them said, “Rob, you are crazy. Don’t you understand railroads are dying? We can understand if you want to be in transportation, but go to work for a good transportation company, like TWA or Pan Am.”

After commencement at Harvard, I drove back across the country with a friend who attended Columbia University, taking a southerly route. The first Southern Pacific towns we reached were Tucumcari and Carrizozo, windy little crew-change places in the New Mexico desert and a long, long way from anywhere. The first thing I did when I got back to San Francisco was to phone the head of the training program. Are you going to make me go to towns like these, I ask? Oh no, he says. We can fix it so you don’t have to do that. Of course, he lied.

![]()

Breaking In, Breaking Bones

2 SOUTHERN PACIFIC was an iconic railroad, the first of any size in the American West. Its roots go back to June 28, 1861, when four enterprising Sacramento storeowners—Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington, and Leland Stanford—chartered the Central Pacific Railroad of California. Even America’s bloody civil war, which had commenced a few months earlier, couldn’t squelch popular demand for a railroad to the Pacific Ocean, and Central Pacific held the ace card that would make it part of that undertaking. The brilliant civil engineer Theodore Judah, who was associated with CP, had found and described a path over the Sierra Nevadas of northern California that all others had thought impossible. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862, committing the government to finance a rail line from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to Sacramento, the Big Four (as the owners of Central Pacific were called even then) got their railroad assigned to build the western portion. The reward for their success was ultimately immense wealth. Leland Stanford, who was also governor of California 1862–63, would later build the university that is my alma mater as a memorial to his only child.

In 1868, even before completion of the Pacific railroad, the Big Four took notice of a fledging company named Southern Pacific, which had begun life three years earlier linking San Francisco to Los Angeles by rail and would eventually acquire the property that in 1885 would be merged with Central Pacific under the Southern Pacific name. In the meantime, SP began building east from Los Angeles, completing its own transcontinental railroad to New Orleans in 1883.

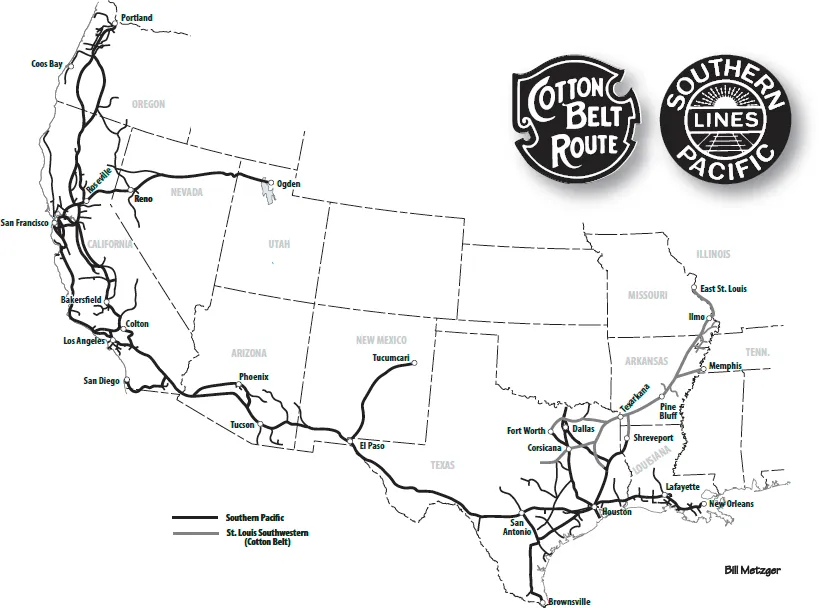

Visualize this railroad as it came to exist in the twentieth century: a broad, 3,200-mile arc that began in Portland, Oregon, extended south through Oakland and Los Angeles, swept east over the Great American Desert to El Paso, continued on across Texas, and finally ended up in New Orleans. Three critical appendages jutted from this arc: first, the 790-mile former Central Pacific line from Oakland and Sacramento to Ogden, Utah, and a connection with Union Pacific to Omaha and Kansas City; second, a 332-mile main line from El Paso to Tucumcari in New Mexico, where it met the Rock Island Lines from Chicago and Kansas City; and third, the St. Louis Southwestern Railway—everyone called it the Cotton Belt—which operated 756 miles from a connection with SP in East Texas to East St. Louis, Illinois, where it traded freight cars with all the major eastern railroads. I would get to know the Cotton Belt, which Southern Pacific bought in 1935, in the not-too-distant future.

When I went to work for Southern Pacific in 1966, it remained a mighty company, a class act among American railroads, and the biggest of all rail systems in the things that seemed to matter most: route miles (13,587), revenues ($927 million), and net income from operations ($216 million). Its main lines and branches covered the two fast-growing empires of California and Texas: with industrial spurs making their way into every part of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Oakland, and Houston. Southern Pacific could call itself America’s grocer, hauling trainloads of perishable farm products—potatoes, melons, lettuce, and so on—every day from the Central and Imperial Valleys of California and the Rio Grande Valley of Texas. No railroad handled more carloads of wine than SP. The forest products that fueled the explosive growth of California from the 1940s to the 1970s came south on Southern Pacific trains from Oregon.

When Time published a cover story on the troubled railroad industry in 1961, it was no accident that its focus fell on Southern Pacific. “Healthy among the Sick” was Time’s cover line, over a photo of a smiling Donald Russell standing amid trains, trucks, and pipelines, all part of the mother company. I don’t remember when or where I saw this magazine story, but I know it influenced my decision to work there. This in-depth and favorable article celebrated Southern Pacific’s rapid modernization (“Russellization” was Time’s phrase) and diversification during the past decade.

All of that was true. Even the storied Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, which I would get to know two decades later, feared the Southern Pacific, its number-one competitor. But in hindsight, the Southern Pacific of the mid-1960s was nearing its inflection point. A wave of megamergers began in 1967, with Atlantic Coast Line and Seaboard Air Line combining along the Atlantic coast to soar past Southern Pacific in route miles. A year later, the New York Central and Pennsylvania railroads would become Penn Central and would briefly be number one in route miles, revenues, and net income—only to fail miserably two years later. And in 1970, Burlington Northern would emerge from six railroads, creating a system extending from Seattle to Houston. Southern Pacific could meet such challenges as these, and seize the opportunities that arose, to rise to new heights. Or it could drift and be overtaken by events and structural changes in its industry and the economy. Which would it be?

I couldn’t foresee all this or answer that question. I was new to railroads and new to Southern Pacific. My nose at that time was close to the ground. But the management training program that I entered gave its participants a view of every aspect of railroad operations. Department by department, I would learn how things got accomplished.

Each department of the railroad occupied a floor at 65 Market Street. My enduring memory is of floor upon floor of clerical employees sitting at endless rows of desks, surrounded by huge piles of papers or books. One huge battalion of clerks did rate divisions, which were intercompany settlements when more than one railroad handled a loaded car. I learned that at one time, the largest craft in railroading was not engineers or conductors or maintenance-of-way workers, but clerks. In my two years as a trainee, I sat with almost every chief clerk in the building, in every little bailiwick, learning what it was they did.

The first thing trainees did, however, was go out for about three months and work as a switchman. Switchmen perform the most fundamental (and sometimes the most physically challenging and dangerous) work in railroading, moving freight cars in order to build the trains that will take them to their destinations. The railroad’s thinking was that if you’re going to manage these people, you need to walk in their shoes for a time and understand their jobs. On my second week at Southern Pacific, I showed up at the yard in East Oakland, having been given exactly one day of training. I brought a lantern and my lunch.

Our engine coupled to a cut of freight cars, and the foreman said, “Ride this car and when it clears the switch, signal the engineer to stop and then reverse the switch and shove the cars onto the adjacent track.” Okay, I could do that. But I asked, “Is there any special way to get on and off the cars when they are moving?” He said no, just do what comes naturally.

I stepped into the stirrup at one end of the boxcar, holding on to the grab iron. We moved down the lead and reached the switch where I must get off, probably doing 5 or...