eBook - ePub

Socially Just Practice in Groups

A Social Work Perspective

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Socially Just Practice in Groups: A Social Work Perspective comprehensively covers all aspects of group practice in social work settings, integrating a unique social justice framework throughout. Drawing from their experience as group work practitioners, authors Robert Ortega and Charles D. Garvin walk readers through the basics of group practice, including getting started, doing group work, establishing the purpose, roles and tasks of the group, stages and phases of practice, and specific skills in assessment, monitoring, and evaluation. A social justice framework provides a fresh perspective during an era of widespread social change and provides social workers tools for effective group interventions. Chapters contain detailed case examples to illustrate concepts presented, as well as exercises to help students practice skills.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Socially Just Practice in Groups by Robert M. Ortega,Charles D. Garvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Sozialarbeit. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 What Is a Socially Just Approach to Group Work?

In our introductory chapter, we offer a definition of social justice, core practice principles, and a survey of themes and topics of the book that we believe are critical in laying the foundation for social justice practice in groups.

Most texts written about working with groups emphasize their ubiquity and the multiple purposes that groups serve. In today’s complex and global society, groups become especially important in meeting the multiple challenges experienced by members facing a myriad of social conditions, environmental adaptations, and human needs. Core elements of work with groups include helping members become a system of mutual aid, utilizing group processes to assist in the helping process, and maintaining the importance of social functioning to autonomous individuals and as members of the group (Garvin, 1997; Middleman & Goldberg, 1974). A focus on optimizing social functioning directs our attention toward individuals and their embeddedness in contexts that include themselves, their social interactions, and the environments in which they function as contributors to understand needs, capacities, and opportunities for change.

Group work from its earliest inception was about member empowerment and collective action for personal and social change. In the extensive history of social work in groups, we begin with the early settlement house movement. This initiated the evolution of community-based participation in response to an array of social problems relevant, for example, to immigrant segregation, oppressive child labor practices, unsafe work conditions, and poor access to health services. The history involved a continuous process of bringing people together, finding support in each other to fight against insurmountable odds, and gaining insights and skills from each other. Social justice group work aimed then and now to form networks of supportive relationships in which power and control are shared.

Much of social justice work has tended to focus primarily on combating injustice. By inference, this perspective views justice as the absence of injustice. Without a vision of what social justice can be, however, work in groups may address some problems and improve some difficult conditions, but it is less likely to contribute to sustained progress toward socially just goals. In socially just practice, we build on theoretical concepts that draw upon the duality of recognizing various forms of social injustice and movement toward social justice in groups.

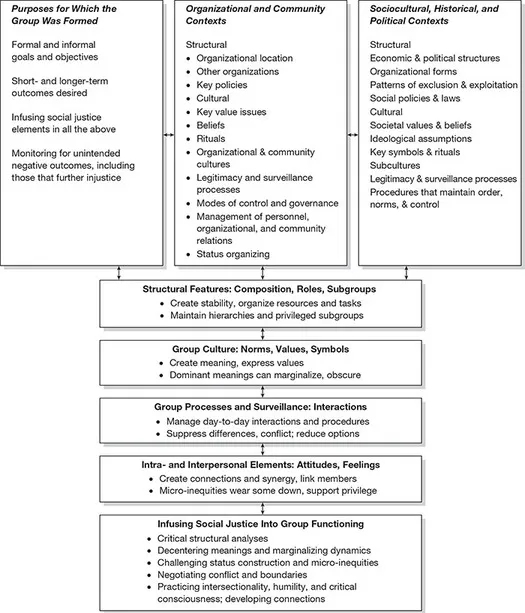

In our focus on socially just practice, we conceptualize small group as an embeddedness in social justice contexts for practice considerations (see Figure 1.1). We revised our conceptual framework from the one we presented in Roberta R. Greene and Nancy Kropf (eds.), Human Behavior Theory: A Diversity Framework (2nd ed.). That book was devoted to social and behavioral science theories utilized by social workers. In our chapter in that book, we considered how this conceptual perspective can be used with diverse populations, particularly in ways that promote empowerment and social justice (Reed, Ortega, & Garvin, 2010). This framework was further described in subsequent literature (Reisch & Garvin, 2016).

Figure 1.1 Social Justice and Small Group Components and Theory

Source: Revised conceptual framework from Reed, B., Ortega, R. M., and Garvin, C. (2010). Small group theory and social work: Promoting diversity and social justice or recreating inequities? In Roberta R. Greene and Nancy Kropf (eds.), Human behavior theory: A diversity framework (2nd ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publications. (Figure 9.1, p. 211)

Conceptually, we consider a multi-systemic and structural–functional model that depicts the interrelated domains important for understanding small groups, including frames for understanding power not merely as a detriment to equity and inclusion, but also containing the contexts in which possibilities for social justice can come about (Reed et al., 2010). Our model considers the functions to be fulfilled by the group, as well as desired outcomes of the group’s activities. Sociocultural, historical, economic, and political contexts are included, as well as community and organizational environments in which members and the group are embedded.

Our conceptual model draws attention to structural features of the group and how the group is organized; group culture (norms, values, symbols); group processes and procedures (how group members do things together); and intra- and interpersonal elements (including facilitator and member attitudes, values, and behaviors). Our framework also considers structural and functional aspects of the environment and their impact on the multiple components of small group. This includes group participant abilities to work together, influence each other, and the group’s ability to affect environments that contribute to injustice. And finally, our model identifies a component depicting the ways group leadership works toward justice in small groups. It includes infusing social justice processes and disrupting the multiple forces acting as impediments to furthering the goals of social justice, reducing injustice, and guarding against unintentionally contributing to mechanisms that support and maintain unjust privilege and oppression (Reed et al., 2010).

Defining Social Justice

Pursuing the goals of social justice are complicated because even in defining social justice, conflicting perspectives emerge (Reisch & Garvin, 2016). A common social work definition of social justice describes it as

an ideal condition in which all members of society have the same basic rights, protections, opportunities, obligations, and social benefits. Implicit in this concept is the notion that historical inequalities should be acknowledged and remedied through specific measures. A key social work value, social justice entails advocacy to confront discrimination, oppression, and institutional inequities. (Barker, 2003, pp. 404–405)

Our definition of social justice recognizes that group members enter the group with different capabilities based on historical opportunities, multiple environmental influences, and meaning making that integrates one’s intersectional identities with culturally adapting coping strategies, and decision making (Garvin & Ortega, 2016; Reed et al., 2010). A capabilities perspective requires us to build on and use our diversity effectively in all group interactions and activities. Social justice group work from this perspective, for example, encourages members and the group as a whole to ask if the group’s purpose addresses relevant issues of diversity for the particular members and the group’s embedded contexts. Additional consideration includes the degree to which the group’s goals relate to the unique experiences of oppression encountered by each member and as expressed by these members, themselves.

Reisch and Garvin (2016) further our definition of social justice by reminding us that social justice principles apply to the basic structure of society that determines the assignment of rights and duties in the context of citizenship and that regulates the distribution of social and economic advantage. A social justice perspective asserts that unequal distribution based on core contingencies such as race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status and that results in social or economic advantage and disadvantage attributed to these contingencies, requires redress so that all persons are treated equally (Reisch & Garvin, 2016). Reisch (2002) draws attention to Rawls’ (2001) principles of justice, which posit that social values are to be distributed equally unless unequal distribution of all (or any) of these values is to everyone’s advantage. In this sense, a social justice perspective asserts that any resources present in an organization’s structure must be accessible to all and be to everyone’s advantage. Hence, socially just practice includes the extent to which group procedures and practices identify and reduce or eliminate undesirable encounters of injustice within the group and between the group and its embedded environments. At the same time, we must consider group procedures and practices aimed at identifying and promoting socially just practices. We assert that the success of social work practice in groups is guided by practice principles drawn from social justice knowledge in pursuit of the dual goals of redressing impediments to, and promoting, socially just outcomes (Garvin & Ortega, 2016; Ortega, 2017; Reed et al., 2010).

Social Justice Practice Principles

Central to our social work mission as group work practitioners is building on individual experiences in ways that support personal growth while allowing members to benefit from the experiences of others. In doing so, group workers are mindful of how bringing people together has both benefits and challenges. Garvin and Ortega (2016) state,

In groups, we seek to pursue social justice goals by asking the following guiding questions: “Do the group’s purpose and goals accommodate issues of diversity and social justice that are relevant to its members both inside and outside the group?” “Does the group experience take into account the individual member differences, including their various positionalities and standpoints?” “Do the group’s dynamics that emerge within the group shape or influence group participation in social just ways?” “Does the group’s leadership respect each member’s unique background, perspective and contributions?” “Does the group’s processes contain built-in responses that identify and address power dynamics and potentially counterproductive actions, appropriately manage conflict, and prevent undesirable outcomes?” Finally, “In what ways do core group work processes support ethically-based socially just group work practice(s)?” (p. 166)

In this book, we elaborate on these questions with examples and practice application of important concepts.

With the above questions in mind, we present the following core practice principles that frame our approach(s) and that are core to the development of this book:

- The group’s goals and purpose must be inclusive of social justice goals of the participants and host context in which they develop and perform.

- Member relevance including unique intersectional social identities, needs, and experiences of each of its members both within and outside the group are recognized, appreciated, and valued.

- The group’s norms must support socially ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Section I Historical and Conceptual Approaches to Group Work and Social Justice

- 1 What Is a Socially Just Approach to Group Work?

- 2 History of Group Work

- 3 Knowledge for Practice

- 4 Models of Group Work and Relationship to Social Justice

- 5 Group Purposes

- 6 Values and Ethics

- 7 Roles, Tasks, and Critical Consciousness

- 8 Leadership

- Section II Doing Group Work for Social Justice

- 9 Group Processes and Development

- 10 Assessment

- 11 Preparation for the Group Meeting

- 12 Group Beginnings Formation

- 13 Approaches to Achieving Different Purposes

- 14 Activities

- 15 Task Groups

- 16 Environmental Change

- 17 Termination and Endings

- 18 Evaluation

- Index