- 584 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Culture and Psychology

About this book

Using an engaging storytelling approach, Culture and Psychology introduces students to culture from a scientific yet accessible point of view. Author Stephen Fox integrates art, literature, and music into each chapter to offer students a rich and complete picture of cultures from around the world. The text wholly captures students' attention while addressing key concepts typically found in a Psychology of Culture or Cross-Cultural Psychology course. Chapters feature personalized, interdisciplinary stories to help students understand specific concepts and theories, and encourage them to make connections between the material and their own lives.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One Introduction to the Psychological Study of Culture

Chapter 1 Outline

- 1.1 The Journey of Culture

- Psychology and Culture

- 1.2 What Is Culture?

- The Problem of Defining Culture

- Defining Culture in the Social Sciences

- Our Operational Definition

- SPOTLIGHT: Behind Customs: Shoes Inside or Outside?

- 1.3 A Very Brief Prehistory of Human Culture

- Earliest Evidence of Modern Human Origin

- Accelerating Cultural Complexity

- Is Culture Uniquely Human?

- 1.4 Structural Components of Human Thought

- Bigger Brains: The Social Brain Hypothesis

- Theory of Mind

- Components of ToM

- The Last Hominid Standing

- 1.5 Human Groups

- Evolution of Groups

- Core Group Configurations

- 1.6 Communication and Innovation

- Life and the Art of Creating Culture

- Rapid Change and the Advent of Humanity

- SPOTLIGHT: Toi: That Which Is Created

- 1.7 Elements of Culture: Putting the Pieces Together

- Parameters of Culture

- Arts, Culture, and the Human Mind

- Taonga Tuku Iho

- Why We Will Use Arts as a Theme Throughout the Text

Learning Objectives

- LO 1.1 Explain the relevance of culture to psychological research.

- LO 1.2 Evaluate existing definitions of culture and their relevance for cultural research.

- LO 1.3 Describe evidence of factors that made human culture possible.

- LO 1.4 Identify brain structures that enable human thought and communication and relevant theories about human social interaction.

- LO 1.5 Describe configurations of basic human groups.

- LO 1.6 Discuss the rise of symbolic thought and communication and its effect on rate of innovation in human culture.

- LO 1.7 Explain how cultural products and processes provide evidence of basic psychological parameters of culture.

Preparing to Read

- What comes to mind when you think of the word culture?

- What is/are your culture(s)?

- Have you ever had to interact with someone whose actions seemed strange or difficult to understand because he or she came from another culture?

If you were moving from island to island around the Pacific a few thousand years ago, during the Great Pacific Migration, you would have traveled by waka (Māori), also called wa‘a (Hawaiian) or canoe (English). These were not simple carved logs; they were durable and sophisticated ocean-voyaging vessels that had sails and outriggers for speed and stability and were capable of journeys covering thousands of miles. The risks and planning required were as daunting as a journey to Mars, perhaps with less chance of surviving or returning. The navigators steered by stars and currents in ways still never mastered in the West. They eventually settled the largest maritime expanse in the world, from the Maldives in the Indian Ocean to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east, to Hawai‘i in the north, to Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the south. One such vessel, the Hōkūle‘a, recently circumnavigated the globe with the crew using only traditional navigation by stars and currents (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Canoe From New Zealand at a Gathering of Traditional Deep-Sea Voyaging Canoes From Across the Polynesian Triangle at Keehi Lagoon

Source: tropicalpixsingapore/istockphoto.com

Waka were crucial in the lives of Polynesians and, as such, held metaphorical and practical meanings that filled Polynesians’ explanations of life and the world. Waka provide conveyance from one place to another. Something that takes you from one way of knowing to different understanding is a metaphorical waka. A teacher is like a navigator who guides your journey of learning. A textbook is a language vessel that carries knowledge from one person to another. This text is a vessel to help you reach greater understanding of how people live and think in cultures unlike your own and how culture has shaped you as you live in your culture.

Why It Matters

This text will challenge your ideas of how people think and feel and why they believe and act as they do. One frequent assumption is that Western culture, that of Europe and its colonial descendants, is the pinnacle of human thought and achievement. How do you feel about the idea that a few people could set out on a hand-crafted vessel without even a compass to sail around the whole earth? People from Polynesian traditions hold continuing bodies of knowledge stretching back thousands of years before Europe developed civilization. Did your upbringing prepare you for challenges like that?

1.1 The Journey of Culture

LO 1.1: Explain the relevance of culture to psychological research.

‘Ike Pono speaks to clear and certain comprehension and understanding; to recognize and understand completely and with a feeling and sense of righteousness.Native Hawaiian Hospitality Association, 2013

Humans have explored and settled the entire earth, with every land mass and stretch of water mapped and catalogued, so that even those who cannot navigate by stars and currents have GPS to draw upon. As we spread around the planet, though, we forgot our common origins. We now speak thousands of different languages and, more important, we approach life from different perspectives. We have branched into completely disparate, often conflicting, ways of viewing life, nature, the universe, and our fellow humans.

As we expanded, we developed different technological abilities, including the capacity to blow up the entire planet. Because we have forgotten our common origins, violence erupts with alarming frequency on local to international levels, ranging from military attack to less obvious violence done by embargos and inequitable distribution of resources. These factors claim millions of lives each year. Ultimately, our survival as a planet and species depends upon intercultural understanding and cooperation. We may be able to observe and describe the many lights in the night sky, but we can only live on one tiny planet so far.

This book intends to convey you to greater understanding of how people learn to feel and think as members and products of cultures. All humans share formative and functional processes, even if the resulting person ends up very unlike you, but understanding how culture shapes the person can help us to appreciate the vast diversity of human culture. Hopefully, those who read this text will end up able to empathize a bit with even the most different person because we all share the same DNA and we all have to survive on this one little marble spinning across the vastness of space. The better we know our fellow passengers on this planetary waka, the more we can accommodate varied points of view, the better we are equipped to negotiate solutions, and the less likely we are to use lethal violence to achieve our goals.

Psychology and Culture

A culturally sensitive psychology . . . is and must be based not only upon what people actually do, but what they say they do and what they say caused them to do what they did.Bruner, 1990, p. 16

Humans are unquestionably social creatures. People require parents, at least for biological reproduction, and someone must nurture us for our first couple of years. Our food, shelter, and clothing must be made, and even if we learn to make all of that ourselves, the knowledge we need is socially transmitted to us from those who came before. Humans exist, according to Caporael and Brewer (1995), in an unavoidable state of obligatory interdependence: human life is the product of thousands of years of cumulative and continuing social cooperation (Richerson & Boyd, 2008). The accumulations of habits, knowledge, and beliefs we have collected along the way form building blocks of culture.

Our lives are full of interactions with other people—parents, siblings, friends, or employers, along with the tellers, cashiers, bus drivers, and physicians who are occasionally encountered in our social convoy (see Figure 1.2), a concept that includes all those who accompany us through our daily journeys (Kahn & Antonucci, 1980). In all cultures, there are things people are encouraged to do and activities that are discouraged, either by laws, morals, or community pressures. Our interactions are governed by these rules, in the form of norms and customs that are culturally determined. We have certain bodies of knowledge instilled in us as we grow, so that we are toilet trained and can read textbooks or tend a flock of goats. We know what to eat and what is going to make us sick; this is a very important body of knowledge. We learn our collections of knowledge in particular ways, whether in a school, on a farm, or in a hunting party. We share these broad categories of learning and acting, yet we differ in the details of every one of them.

Figure 1.2 Social Convoy Elements of Common Social Interactions

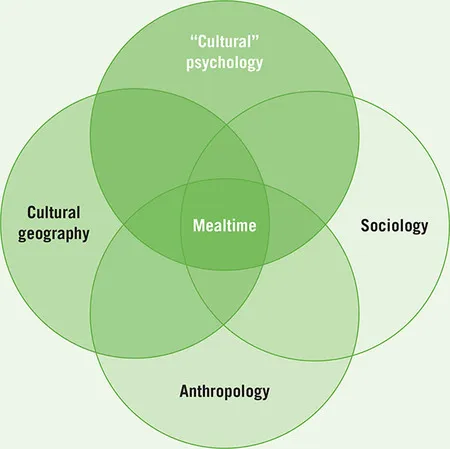

For our purposes, the general goal of psychological science is to explain the laws by which individual minds work, and we will explore aspects of this study throughout the book. Bringing culture to the study adds inevitable overlapping of interests with disciplines such as anthropology, cultural geography, and sociology, for instance when we examine the ways different cultures approach mealtime (see Figure 1.3). Does the family eat together at one time? Are they separated by gender? Are members served in order of age, rank, gender, or hunger level? A cultural psychologist might look at how meal sharing affects an adolescent’s senses of connectedness and well-being (Crespo, Jose, Kielpikowski, & Pryor 2013).

Figure 1.3 Venn Diagram of Mealtime as a Topic of Study

The questions asked and the approaches used lead to very different answers in the various disciplines. In psychology, culture ultimately can illuminate both how individual cognition and resulting action shapes our larger collective social structures and how cultures simultaneously shape the individual (Schaller, Conway, & Crandall, 2004). Gelfand and Kashima (2016) propose that “culture is essential to human psychology” (p. iv), such that no real understanding of humans is possible without inclusion of these cultural forces.

Obviously, there are differences between cultures. The question for psychology is whether culture makes a difference in areas that are normally the domain of psychology, such as cognition, emotion, or development. As shall be discussed, the science of psychology emerged primarily from Europe and America, and the overwhelming body of research has been conducted by researchers from those cultures, with people (mostly students) from those cultures as participants in their studies. Given psychology’s broad goal of finding universal laws to describe and explain behavior, the discipline’s laws, theories, and assumptions should hold true for all humans, but differences continue to emerge. Psychology programs can now be found in most countries, from Afghanistan (Kabul University) to Zimbabwe (University of Zimbabwe), providing more perspectives and diversity of data. In cultural research from all over the world, effects of culture are being observed scientifically, and a culturally informed body of literature is growing.

To illuminate the relationship between mind and culture, this text will use past and current research and real-life examples, along with creative expressions found in the arts, music, and literature of different cultures. Perhaps we take our shoes off at the door of a house when we enter, or perhaps our host gets profoundly uncomfortable upon seeing our unshod feet, and that may constitute a droll difference we can laugh about at parties. Behind that slight difference in custom may lie hundreds of generations of thought, transmitted and modified across the centuries, and reflecting very sound hygienic practice or spiritual wisdom shaping our preferences. Particular customs are fascinating in their many forms, but how do they come to be, and why are they so very different? How are they expressed, transmitted, and enforced and why? What do they mean to us and to others? These questions, regarding underlying beliefs and motivations and not simply whether or not someone wears shoes inside the house, are what we will study.

As Bruner (1990) proposes, a culturally sensitive psychology asks why we do particular things and why we think we do them. Unlike behaviorist John Watson (1913), who was only concerned with observable behavior, we are concerned with the cognition behind the action. Subtleties of culture are often so deeply ingrained that we are unaware of them unless we encounter something that runs contrary to our norms, such as bumping into someone while walking down a sidewalk in a country that passes on the opposite side from our accustomed norm. Humans have a common genetic propensity for right-handedness, but norms of passing another pedestrian or car are learned and then automated beneath our active level of consciousness. Culture forms the canvas and palette with which we paint our lives in frameworks passed down for generations, and consciousness of the rationale may be lost to history; few people are aware that Americans drive on the right because Napoleon changed traffic flow so that habit would unmask British spies in France, and America adopted his scheme. Eras and situations color our individual lives, set against shifting sociocultural backgrounds as history marches on. Within our inherited cognitive frame, each human helps to create relationships and interactions with others, our systems of learning and bodies of knowledge, and our philosophical and moral systems. The different ways these common parameters are flavored by culture and circumstance make our collective creation of life on earth a fascinating tapestry of diversity.

Reality Check

- Have you encountered people from other cultures this week?

- Was there anything about their actions that seemed unusual to you?

- How have cultural differences shaped events in the news this week?

1.2 What Is Culture?

LO 1.2: Evaluate existing definitions of culture and their relevance for cultural research.

The Problem of Defining Culture

Culture is our topic of study, but what is it? We use the term culture without much thought, and everyone seems to know what we mean, at least in casual conversation. Anyone speaki...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Brief Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction to the Psychological Study of Culture

- Chapter Two Cultural Processes

- Chapter Three Research Considerations and Methods for Cultural Context

- Chapter Four The Self Across Cultures

- Chapter Five Lifespan Development and Socialization

- Chapter Six Close Relationships

- Chapter Seven Cognition and Perception

- Chapter Eight Communication and Emotion

- Chapter Nine Motivation and Morality

- Chapter Ten Adaptation and Acculturation in a Changing World

- Chapter Eleven Health and Well-Being

- Chapter Tweleve Living in a Multicultural World

- References

- Name Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Culture and Psychology by Stephen Fox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.