![]()

1 Records That Matter: Improve Your Community, Career and Life

Access Action Agenda

- ☑ Make the world better

- ☑ Advance your career

- ☑ Improve your personal life

- ☑ Develop a new way of thinking

A watershed moment in the debate over police shootings came as the result of a public records request by then-29-year-old freelance journalist (and restaurant worker) Brandon Smith.

Smith, like countless other Chicago-area reporters, was following the tragic saga of the shooting of Laquan McDonald, who was fatally shot in 2014 by Officer Jason Van Dyke.

Initially, police representatives told reporters that Van Dyke had acted in self-defense as McDonald lunged at him with an open knife. They said Van Dyke and a partner responded to a call that someone was trying to break into cars in an industrial area on the southwest side of Chicago. The officers found McDonald standing in the street with a knife. They observed him stabbing the tires of a vehicle. When they ordered him to drop the knife, he ignored them and walked away, down the street, they said.

“The officers are responding to somebody with a knife in a crazed condition, who stabs out tires on a vehicle and tires on a squad car,” police told reporters that night. “He is a very serious threat to the officers, and he leaves them no choice at that point but to defend themselves.”

But questions remained, and the broader narrative around police shootings kept the story alive. Eyewitnesses publicly questioned the need for gunplay. The department’s description of a single “chest wound” blew up spectacularly after Jamie Kalven, who works with the Invisible Institute, a South Side journalism production company, filed an FOI request for the autopsy report. It turns out that McDonald was shot 16 times.

Smith filed his records request for the dash-cam video in May 2015. By the time he filed suit in August, the police had denied 15 different requests for the footage, including Smith’s, citing the video’s connection to an ongoing investigation. Smith won his case, and the revealed video created global headlines.

When the police dash-cam video of the shooting was released on November 24, 2015, it showed McDonald walking away from the police when he was shot. The knife he was carrying was found to be closed. That same day Officer Van Dyke was charged with first-degree murder.

“All because I knew to ask, and I knew what my rights are,” Smith said. “I took a shot.”

Smith and Kalven got the story because they demonstrated what we call a “document state of mind.” They were thinking about a story in a records-first way, exploring all of the possibilities and, most importantly, never giving up. They were interested enough to persevere, and curious enough to ask for the records in the first place. That’s the first step in becoming a records-driven information sleuth—and it’s as easy as asking and knowing your rights.

In this chapter we’ll start by describing the benefits of documents to your career and your life, providing dozens of examples to inspire and motivate. When you finish reading and then skim The Record Album at the back of this book, we hope you walk away with dozens of ideas for documents that will produce award-winning stories, better your community and improve your life.

Of course, as government digitizes more and more records, and provides those online proactively, masses of information become available at anyone’s fingertips. But that information is just the tip of the iceberg, and usually the best records, the ones that effect positive change and make a difference, are those you have to go after—the ones you must wrangle out of reluctant officials’ hands.

Years of working with requesters have convinced us that (1) anyone can do this, and (2) it has benefits for anyone willing to invest the time.

So, let’s get started.

Make The World Better

Records hold those in power accountable.

When Ted Bridis led The Associated Press’ investigative team in Washington, D.C., he was frustrated by the Obama administration’s excessive secrecy. President Obama had pledged to be the most transparent president, but by many measures he was one of the most secretive.

Then voters elected Donald J. Trump.

“It’s going to be a backyard brawl,” Bridis said soon after the 2016 election.

A year and a half into Trump’s first term, Bridis, teaching journalism at the University of Florida, reflected on his prediction. “I think that was pretty prescient. FOIA responses are down, the government is less responsive. More denials, more delays. Lawsuits are up. This really reflects the fact the president is in a position of authority. The career bureaucrats are taking their marching orders from the top.”

Presidents of different parties come and go, but the power of the office remains, secrecy expands, and public records are a check on that power—at all levels of government.

Pete Weitzel, a reporter and editor at The Miami Herald for nearly four decades, covered city and county government before Florida adopted its open meeting and open records laws, also called sunshine laws. “We often had to cajole, and work the system, and call in favors to get official records,” Weitzel says, recalling urging young reporters at the Herald to “find the anomalies.”

“It’s in the cracks, in the things that just don’t line up, that records turn up gold,” he says. “I remember going through a Dade County financial report on the public hospital and seeing numbers that just didn’t add up. It turned out the hospital was operating at a huge deficit that taxpayers would have to cover. It was a big story, just huge, and it was sitting there for anyone who took the time and initiative to go look at the records and then ask a few questions.”

Identify the ‘Performance Gap’

Charles Lewis, a former “60 Minutes” producer who founded the Center for Public Integrity and the Investigative Reporting Workshop at American University in Washington, D.C., can trace his fascination with records back to his days as a student at the University of Delaware working for the Wilmington News Journal as a part-time sportswriter. He noticed that many of the student athletes were taking far longer to graduate than the school wanted anyone to know.

Realizing that he couldn’t get his hands on the athletes’ transcripts, he sat down and began pondering the records he could get.

“I was learning all about public and non-public information,” Lewis said. “So, I sorted them in my head and realized that I had access to rosters and commencement programs. So, I laid the commencement programs beside the team rosters, and just like that I had my story: nongraduates, six-year kids, the whole deal.

“I was a 19-year-old kid looking at the stark difference between what people said and reality, and it hit me that this is what I wanted to explore,” he said.

Documents help journalists and citizens hold government accountable by identifying the “performance gap.” For example, in 2018, as immigration dominated the news agenda amidst the controversy surrounding the separation of parent and child asylum seekers, the news site Motherboard used a freedom of information request to find that in 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security did not investigate hundreds of civil rights complaints about alleged detainee, prisoner, or suspect abuse filed to the agency’s oversight body.

The government claimed it was taking such cases seriously; its own records showed another story. That gap between what an agency says it is doing and what it actually does—the performance gap—is a critical engine of accountability for reporters and citizens intent on monitoring government performance. Suppose your local police force says that it is stepping up enforcement of speeding violations. That’s an invitation for you to measure the performance a few months later.

Pro Tip: Be like Woodward and Bernstein: Bolster Stories through Public Records

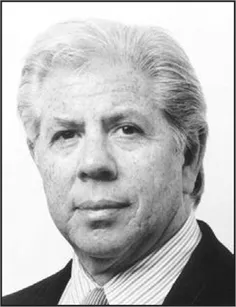

Bob Woodward (top left) and Carl Bernstein (bottom left) used documents and people sources to expose the Watergate scandal and bring down President Richard Nixon. Since then the former Washington Post reporters have used documents for their investigative books. Here is what they told us they think about public records.

Woodward: There has never been a news story I know of that could not be improved or buttressed by a document of some sort. Many, many times these documents are public records, or the reporter can find a source who will decide to add some documents to the public record. Liberating such records for the public good is part of the job of those in government. Documents establish in time, person and authority what has happened or might have happened. They have been, and I hope will always be, part of the record.

Bernstein: Journalists need to make more use of public records. They are there for the taking, usually, and with a little extra effort can be located and perused even when they’re difficult to take.

Photos courtesy of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein

Federal officials assured us that they were getting serious about air safety following the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. The government spent tens of millions of dollars establishing the Transportation Security Administration, whose indignities all air travelers have suffered. Take a minute to develop your document state of mind. What records-driven performance measures can you think of that would allow you to check up on this relatively new and extremely expensive government agency?

Reporters at The Washington Post thought about it and informed readers that Los Angeles International Airport officials had uncovered 12 airport screeners with felonies or other criminal backgrounds just weeks after the federal government said it had “rescrubbed” the backgrounds of its workforce there.1 Several of the 12 screeners working for TSA at the airport had criminal records related to “unlawful use, sale, distribution or manufacture of an explosive or weapon” and held security badges that provide access to secure areas of the airport for more than 200 days.2

That’s the performance gap. Compare what the government says it is doing to what it is actually doing—through its own documents.

Help Society

These great document-driven stories aren’t just fascinating to read. They help society.

First, the mere knowledge that records are being kept, and that some day they will be reviewe...