- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

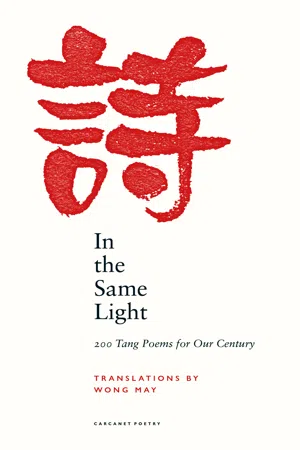

The Poetry Book Society Spring 2022 Translation Choice

Chinese poetry is unique in world literature in that it was written for the best part of 3, 000 years by exiles, and Chinese history can be read as a matter of course in the words of poets.

In this collection from the Tang Dynasty are poems of war and peace, flight and refuge but above all they are plain-spoken, everyday poems; classics that are everyday timeless, a poetry conceived "to teach the least and the most, the literacy of the heart in a barbarous world, " says the translator.

C.D. Wright has written of Wong May's work that it is "quirky, unaffectedly well-informed, capacious, and unpredictable in [its] concerns and procedures, " qualities which are evident too in every page of her new book, a translation of Du Fu and Li Bai and Wang Wei, and many others whose work is less well known in English.

In a vividly picaresque afterword, Wong May dwells on the defining characteristics of these poets, and how they lived and wrote in dark times. This translator's journal is accompanied and prompted by a further marginal voice, who is figured as the rhino: "The Rhino ??? in Tang China held a special place, " she writes, "much like the unicorn in medieval Europe — not as conventional as the phoenix or the dragon but a magical being; an original spirit", a fitting guide to China's murky, tumultuous Middle Ages, that were also its Golden Age of Poetry, and to this truly original book of encounters, whose every turn is illuminating and revelatory.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

AFTERWORD

The Numbered Passages of a Rhinoceros in the China Shop

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元

- Du Fu 杜甫

- Li Bai 李白

- Cui Hao 崔顥

- Meng Hao Ren 孟浩然

- Qian Qi 錢起

- Wang Wei 王維

- Li Shangyin 李商隱

- Zheng Tian 鄭畋

- Wei Zhuang 韋莊

- Chen Tao 陳陶

- Gao Chan 高蟾

- Li Duan 李端

- Zhang Ji 張繼

- Wei Yingwu 韋應物

- Yuan Zhen 元稹

- Bai Juyi 白居易

- Du Mu 杜牧

- Xu Ning 徐凝

- Nie Yi Zhong 聶夷中

- Jia Dao 賈島

- Dou Shu Xiang 竇叔向

- Luo Bin Wang 駱賓王

- Liu Yu Xi 劉禹錫

- Luo Yin 羅隱

- Li He 李賀

- Zhang Jie 章碣

- Li Qing 李頎

- Meng Jiao 孟郊

- He Zhizhang 賀知章

- Cui Hu 崔護

- Han Wu 韓偓

- Cen Shen 岑參

- Li Yi 李益

- Yu Xuanji 魚玄機

- Xue Tao 薛濤

- Han Shan 寒山

- Afterword

- Also by Wong May

- Copyright