Chapter 1

The Elephant in the Room

IN THE INTRODUCTION, WE DISCUSSED the wide and persistent gap between women’s and men’s overall career achievements. We also made clear that this gap is not due to women being less ambitious, competent, or committed to their careers than men. Indeed, the important takeaway is that gender has little or no bearing on leadership ability, career ambition, or commitment.1 Another misconception about the reason for the achievement gap is because of rigid workplace practices. It is often argued that if American workplaces demanded less “face time,” allowed more flextime, permitted more telecommuting, provided more generous paid maternity leave, and created more welcoming reentry programs, women would advance in their careers in a manner comparable to men.

Although these (and other) structural workplace changes are sensible, desirable, and much needed, we seriously doubt that—by themselves—they would do much to end the disparity in women’s and men’s career achievements. The reason is that the fundamental phenomenon holding women back is not structural but psychological: the elephant in the room of the disparity in women’s and men’s career achievement is gender bias. This bias flows from the multitude of stereotypes that the people controlling women’s careers hold about women, men, families, competitiveness, ambition, commitment, and leadership. Unless we recognize the pervasiveness of these stereotypes and find ways to avoid or overcome the biases that flow from them, women will continue to encounter serious obstacles to their career advancement regardless of much-needed structural changes that should be made to workplace practices.

Gender Bias

Gender bias is manifested in the systematic depreciation of women’s competence in relation to men’s. Gender bias can be explicit—consciously motivated, open, and hostile disparagement of women—or implicit—unconsciously motivated, even at odds with a person’s strongly held conscious beliefs. We address explicit gender bias in chapter 3. In this chapter, we focus exclusively on implicit gender bias. Implicit bias is the direct result of the stereotypes people exhibiting such bias hold; therefore, we need to carefully examine those stereotypes.

Gender Stereotypes

Stereotypes are reflexive, automatic, unconscious beliefs, expectations, and preconceptions about the capacities, behavior, and characteristics of various sorts of people. The stereotypes about women and men are based on inescapable biological and physiological characteristics. Sex characteristics are unique among a person’s other characteristics, however, for at least four reasons:

- Identifying a person as either female or male is not optional; everyone does it automatically with respect to everyone—including themselves. There is no escaping that categorization.

- Once we identify a person as of one sex or the other, we tend to categorize them as a woman or a man, and it is extremely difficult to alter that characterization. That person is a she or he, period. (Sexual identity and transgender issues blur this point, but its basic thrust remains valid.)

- We sort people by sex as soon as we hear or see them, and we usually know immediately whether the person is a woman or a man (if we don’t, we are likely to be thrown off balance).

- A person’s sex cuts across all other categories. No matter what other social identities about another person we use to sort them—occupation, status, personality, race, age, or something else—we always sort that person by her or his sex.

Sorting people by sex is, in itself, largely benign, and some researchers suggest this probably has an evolutionary value. But this sorting does not stop with the biological division of the population. Once we have sorted people by sex, we then ascribe to them certain socially constructed roles, behaviors, norms, attitudes, activities, and characteristics we believe are appropriate for women and men. In this way, we turn a person’s sex into their gender. And despite the enormous changes in women’s activities and opportunities over the past 50 years, these socially constructed gender characteristics—the gender stereotypes highlighted throughout this book—have hardly changed at all.

The Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI), developed in 1974, and an extensive 2004 study of gender stereotypes both identified virtually identical sets of characteristics associated with women and with men. According to the BSRI, people expect women to be affectionate, sensitive, warm, and concerned with making others feel more at ease. Men are expected to be aggressive, competent, forceful, and independent leaders.2 The 2004 study found that people still expected women to be affectionate, sensitive, warm, and friendly, while people still expected men to be aggressive, competent, independent, tough, and achievement oriented.3 All of these stereotypes remain operative today. Men are still assumed to be characterized by traits of action, competence, and independence, which are often called “agentic” qualities.4 Women, in contrast, are still assumed to be characterized by traits of sensitivity, warmth, and caregiving, which are often called “communal” qualities.5

Perniciousness of Gender Stereotypes

Why are we making such a big deal about gender stereotypes? If most people think that women are warm rather than assertive and that men are aggressive rather than sensitive, what is the harm? The harm in the workplace is that the traits associated with women are also associated with home and caregiving, while the traits associated with men are also associated with leadership and power. When a woman is assumed to be communal simply because she is a woman, she is also assumed to be suited for “feminine” jobs (such as a nurse, teacher, or administrative assistant) and not for “masculine” jobs (such as an investment banker, line manager, or CEO). This means that women are more likely to be tracked into personnel or assistant roles seen to require warmth and a sensitivity to the needs of others, while men are more likely to be tracked into leadership roles seen to require forceful, competent, and competitive behavior.6

Because of gender stereotypes, most people—women and men—tend to think “men” when they see words such as boss, CEO, and director, and to think “women” when they see words such as assistant, attendant, and secretary. People often have these associations because “it is easier for people to capture and understand information about unknown others that is consistent with the gender stereotype (she is a nurse) than counter-stereotypical information (she is a mechanic).”7

Gender stereotypes create a fundamental incongruity between general expectations of roles and behaviors of women and those of leaders. Thus, people think (perhaps unconsciously) that women should be caring, while leaders should be decisive; women should be modest, while leaders should be assertive; women should be helpful, while leaders should be independent. In other words, gender stereotypes contribute to the idea that women are less appropriate leaders than men—and when women behave in ways thought to be appropriate for leaders, they are often subject to backlash in the form of criticism—not praise or recognition.8

Ridding Ourselves of Gender Stereotypes

Of course, gender stereotypes do not reflect reality. As we have made clear, women and men are not inherently different in significant nonbio-logical ways. Why then can’t we simply end gender bias by telling ourselves to stop thinking in terms of these misleading stereotypes? After all, the only reason anyone unconsciously discriminates against women in making career-affecting decisions such as assigning challenging projects to men rather than women is because the stereotypes he (or she) unconsciously holds led him (or her) to expect that men would perform the projects better than the women. Therefore, if we—all of us—would just stop allowing stereotypes to influence our career-affecting decisions, we would be free of implicit gender bias and workplace discrimination against women would end. Wouldn’t that be nice! Unfortunately, eliminating gender bias is not so simple.

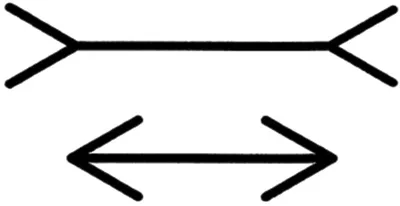

To understand why, it is useful to draw on an analogy with the Muller-Lyer optical illusion with which many readers may be familiar:

In looking at the two lines, we—all of us—see the top line as longer than the bottom one. It does not matter that we are told the two lines are exactly equal in length or that we measure the lines to confirm they are equal. Regardless of consciously knowing the lines are equal, we don’t see them as equal. The same thing is true of gender stereotypes. It doesn’t matter that we consciously know women and men are fundamentally equal with respect to ambition, talent, commitment, and competitiveness. Because of gender stereotypes we don’t see them as equal in these respects.

That is not to say that women cannot do a great deal to avoid or overcome the discriminatory consequences of gender stereotypes—precisely the focus of this book—or that organizations cannot do a great deal to prevent gender stereotypes from having a discriminatory impact on the decisions affecting women’s careers—precisely the focus of the last chapter of our book It’s Not You, It’s the Workplace.9 But it is to say that we cannot break through bias by simply telling ourselves to stop thinking in terms of gender stereotypes.

Gender Stereotypes Are Scripts for Discriminatory Behavior

Stereotypes operate both as sorting mechanisms and behavioral guides. Thus stereotypes “help us” assign people to particular categories (friend, foe; desirable, undesirable; forceful, deferential; competent, incompetent). And thus once we have sorted them, stereotypes also “tell” us how we should relate to the people we have assigned to those categories.

To put this a different way, stereotypes are generalizations: all people who are X are like Y and, therefore, they should be treated like Z. Because not all people who are X are like Y, we are prone to misjudge particular individuals’ actual characteristics, abilities, and potentials. And as a result, because we have mischaracterized certain people who are X as being Y, when we act like Z toward then, we are likely to behave toward them in inappropriate and discriminatory ways. For example, managers may well pick an all-male negotiating team because they (unconsciously) believe that “men are more competitive than women,” even though if they had examined each individual’s actual characteristics, it would have been quite apparent to the managers that several of the women were better negotiators than the men they actually selected.

People generally believe they don’t make such discriminatory decisions, that they do not rely on stereotypes in judging other people, and that they are free of the biases these stereotypes foster. Psychological and sociological studies, however, make it clear that virtually all of us have implicit biases. As Mahzanin Banaji and her colleagues point out, “Most of us believe that we are ethical and unbiased. We imagine we’re good decision-makers, able to objectively size up a job candidate or a business deal and reach a fair and rational conclusion that is in our, and our organization’s, best interests. [More than two decades of research, however,] confirms that, in reality, most of us fall woefully short of our inflated self-perception. We’re deluded by … the illusion of objectivity, the notion that we are free of the very biases we are so quick to recognize in others …. The prevalence of these biases suggests that even the most well-meaning person unwittingly allows unconscious thoughts and feelings to influence seemingly objective decisions.”10

Al: On a recent flight from Chicago to Washington, DC, an airline employee sat next to me on her way home. The weather had been terrible, flights had been canceled over the past two days, and I was pleased my flight had boarded. The airline employee said she was flying home after having been called up at 1:00 a.m. for an early flight to Chicago. She was now flying back to her base in DC and then to her home in Roanoke, Virginia. I thought to myself, “Why would the airline call up a flight attendant as far away from DC as Roanoke?” I then turned to really look at my seatmate for the first time and saw she had stripes on the sleeves of her jacket and a hat in her lap. She was a pilot.

My unconscious stereotypes had been at work: women in uniforms on airplanes are almost always flight attendants; men in uniforms are pilots. Now, while it may have been statistically unlikely for her to be a pilot, I had clearly categorized her incorrectly, albeit relatively harmlessly in this case. But would it have been harmless if I had been in charge of hiring airline pilots and a woman had applied for the job? Would that woman have had a harder time getting my endorsement than a man would have had? I hope not, but I think about that female pilot every time I find myself about to make a categorization of a person based on gender, race, age, or another social identity.

How Gender Stereotypes Lead to Discrimination against Women

Women pursuing careers in gendered workplaces are subject to particularly discriminatory stereotypes. Because of traditional gender stereotypes, both women and men are twice as likely to hire a male candidate than an equally qualified woman.11 Women are 25 to 46 percent more likely to be hired if their gender is not disclosed.12 In addition, almost half of women (42 percent) report having faced discrimination on the job because of their gender; and women with postgraduate degrees report gender discrimination at an even higher rate of 57 percent.13

The biases fostered by gender stereotypes typically function among men in tandem with their sense of male privilege. Such a sense of privilege involves the (usually unconscious) assumption that they are superior to women at valued workplace roles, tasks, and challenges; are entitled to preference over women with respect to career opportunities, resources, and sponsorships; and are immune from criticism for anger, aggressiveness, and self-promotion—conduct that is severe...