![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE GOLD MEDAL COUNTRY

If you ask someone which country ranks first in global competitiveness in business, the most common answer would be the U.S. or Singapore or Japan. All would be wrong. It’s Finland. Finland? Surely someone has made a statistical mistake, or is it a flash in the pan?

Not so. The Growth Competitiveness Index ranking by the World Economic Forum placed Finland first already in 2001, followed by the U.S., Canada, Singapore, and Australia. But that was only for starters. In 2003 Finland outranked the U.S., Singapore, and all others in global competitiveness, reflecting the ability of a country to sustain its high rates of growth based on 259 criteria, including the openness of the economy, technology, government policies, and integration into trade blocks.

Will they be able to maintain their lead?

It would seem so. Such respected journals as The Economist and the Financial Times have recently entitled articles “The Future Is Finnish.”

What are the grounds for such an assumption?

They are numerous. Finns seem to invest their efforts (and often their money) in areas designed to guarantee a healthy and prosperous future. Starting with education, they came first in an Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) survey of European standards of reading and mathematical and scientific literacy (2003). Worldwide, only the Koreans matched them in these fundamental skills. In Europe, Finland leads all other countries in postsecondary enrollments by 12 percent.

Do they plan on remaining the best-educated people on the continent?

In the world, in fact. They are in the top two countries in the economic creativity index, and they are trailing only Sweden and are well ahead of the U.S. in research and development (R&D) spending (as a percentage of GDP). They are global leaders in e-banking, have the highest Internet and mobile phone penetration, have a 100 percent digital fiber-optic network, and are home to 10 percent of all Europe’s new medical biotechnology companies.

All this sounds pretty high tech, but more than that, they are high tech where it counts. Apart from their dominance in mobile phone technology, information technology (IT), and pulp and paper products, they have secured their environmental future by concentrating on such issues as water management, human vulnerability to environmental risks, resource sharing, and assimilation of waste.

All this leads one to the conclusion that their future is very bright indeed. They are easily number one in the Economist Environmental Sustainability Index (2004). Only Norway, Sweden, and Canada come close. As is generally recognized, the supply of clean water is one of the vital issues of this century. Finland heads the list in access, supply, use, resources, and environmental impact.

What about the economy?

Strategically situated between Russia and the EU, also with good markets in the U.S., Finland is pretty well balanced. It was not just by chance that in 2000 Nokia was Europe’s biggest company by capitalization. But surely Nokia is Japanese? Not so. Nokia is Finnish born and bred, operating on Finnish turf and until recently with an all-Finnish board of directors.

If one asks how a Finnish company could grow bigger than Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz, and Fiat, not to mention Unilever and Shell, the answer is in research. In 2001, Nokia employed 18,600 people in R&D at 54 centers in 14 different countries.

Can one suppose that the combination of educational superiority and technological research will enable Finland to continue as a world leader in so many fields?

This is extremely likely, especially as they lead other nations in moral strengths.

What does that mean?

According to up-to-date surveys, Finland tops the league in the Corruption Free Index, are the fastest payers in the European Union, and lead the world in minimal bureaucracy. They are an understated society in an era of hype, media hysteria, and abuse; they prize modesty and straight talking above most other attributes. Paavo Lipponen, the prime minister at cross-century, was voted the least charismatic Finnish politician; he shunned hype and small talk, preferring to do his job seriously. What country other than Finland would have fired the following prime minister, Anneli Jäätteenmäki, because she was guilty of a questionable untruth in her remarks to Parliament? (Think what Berlusconi and Chirac get away with.)

What other country would have fined a young Finnish Internet whiz-kid $75,000 for speeding (linking the fine to his sizeable income)? Another Finnish whiz-kid, Linus Torvalds, the inventor of the Linux operating system, which rivals mammoth Microsoft, was hardly interested in profits, preferring Linux excellence to reflect Finland’s model of social welfare. One senior Microsoft executive attacked Torvalds for being “un-American”!

Finnish humility and honesty were praised unequivocally in the Harvard Business Review by Manfred Kets deVries, Director of INSEAD’s Global Leadership Centre, who admired the Finnish style of management more than any other.

Finns are characterized by fresh and innovative thinking that enhances their national image. They tackle serious subjects, such as care of the young (they are third lowest in the world in infant mortality). In the last few years the Finnish government provided strong leadership to eliminate obesity among school children. By planning the food for free school lunches, child obesity was rapidly cut to 11 percent (cf. Britain, 22 percent).

Finns seem to be a nation of “doers” rather than talkers. What are the secrets of their success?

Finns are mainly silent people who go in for deep thinking, which is facilitated by the synthetic nature of their language. Silence engenders vision, imagination, and calm judgments. Small talk interferes with creative thought. Finns take talking seriously and prefer to use language for something that actually pushes things further on the pragmatic level. The basic rule is “less is more.” Finns are adept at creating formulas that enable them to cope with complex political, social, and economic situations. Their originality is bolstered by consistent pragmatism—see how they prefer to be straight to the point, shunning any form of hype—letting the technical story do the talking.

Why is their English so good?

Another pragmatic decision. It’s the world language. The French, Italians, and Spaniards will pay for their neglect of English in twenty-first-century business. Finns have an obsession with achieving and have created something new to cement achievement: one writer described it as “Finnish world-classness.” The Finnish government helps in promoting this by making decisions of national importance through a “rainbow coalition” (effective since the early 1990s) where all parties respect harmonious relations between industry, academia, and government.

How did a country with no natural resources except trees and long-distance runners succeed in distinguishing itself so strikingly?

Two basic strengths are responsible: Properly managed forest is an ever-replenishing source of riches. And as for the runners, which country won most Olympic medals per capita? It must be the United States. Not exactly. The U.S. is in sixteenth place with 8.3 medals per million inhabitants. Norway is third with 53.1 medals. Sweden is second with 56.3. Any guesses for first? Finland perhaps? Right—106 medals per million.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

FINNISH ORIGINS

“A strange tribe from faraway arrived in this land, where no other people had chosen to live.”

This simple statement of fact—true though it is—is also of an enigmatic nature. How strange was this tribe? From how far away had they come? Who exactly were the Finns? Who were their relatives? How and when did they reach this empty territory and why was it empty, or was it really empty? Which lands did the Finns pass through en route, and why did they not stop off in friendlier climes? If, as it seems, they are linguistically related to the Estonians, Lapps, and Hungarians, how and why did the Hungarians end up on the Danube? What is the significance of these four tribes speaking Finno-Ugrian languages when the rest of Europe’s forty countries express themselves in dominant Indo-European tongues? How on earth have the Finnic languages managed to maintain for thousands of years a linguistic toehold in a bleak and remote corner of northeastern Europe, all the while subjected to enormous cultural and political pressures from the Scandinavian west and the Slavic east? When European languages such as Etruscan, Pictish, Cornish, Pelasgian, and ancient Iberian and Sicilian have disappeared, why are the Finno-Ugrian tongues so resilient that Finnish was, in 1995, accepted as one of the fifteen official languages of the European Union?

Theories of Origin

If indeed the questions asked above appear numerous, far-reaching, and probing, it is because the provenance and origins of the Finnish people are shrouded in the mists of historical and prehistoric time, in no less mystery than that which accompanies the roots and routes of the much larger and more widespread family of peoples, their neighbors the Indo-Europeans.

When the Bona Ventura paper, published in 1597, revealed the affinities of the German and Persian languages, a door was opened to over 400 years of speculation as to the original homeland of the Indo-Europeans. So far none of the three hundred or more hypotheses put forward has gained a widely accepted endorsement.

A parallel discussion regarding the homeland of the Finno-Ugrian peoples has been held for less time than the Indo-European debate (about 150 years), partly on account of the relatively late emergence of the Finnish state, but more particularly because of the establishment and predominance of one hypothesis that can be called the “Migration Theory.”

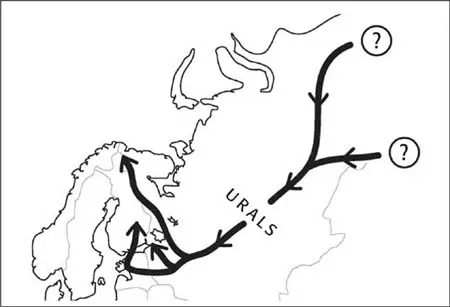

The Migration Theory

According to the migration hypothesis, the Finns migrated from a homeland in northwestern Siberia close to the Ural Mountains. They spoke a Uralic tongue (Finno-Ugrian is related to Uralian and possibly Altaic languages), and they had a Mongoloid element because the ancestral Uralic people were Mongoloids. The migration, which left Finno-Ugrian linguistic footprints all the way from the Urals to the shores of the Baltic, entered its semifinal stages in Estonia and southern Finland around 1000 B.C., about when the Finns separated from the Estonians.

This highly romanticist hypothesis, heroic in terms of territory traversed and its chainlike family of Finno-Ugrian-speaking relatives, held sway in academia for the best part of a century. Its origin was the discovery, by Friedrich Blumenbach, a prominent eighteenth-century scientist and anthropologist, of one Finnish and two Lappish skulls that bore marked resemblances to one Mongol skull in Blumenbach’s possession. This Mongoloid affinity of the Finno-Ugrians was accepted as scientific truth, largely because it received considerable support from linguists.

FIGURE 2.1 The Migration Theory

The Migration Theory (see Figure 2.1), linguist-friendly and neat in many of its assumptions, has come under heavy attack since the 1980s from a number of science-based sources. Enter the geneticists, archeologists, and craniologists.

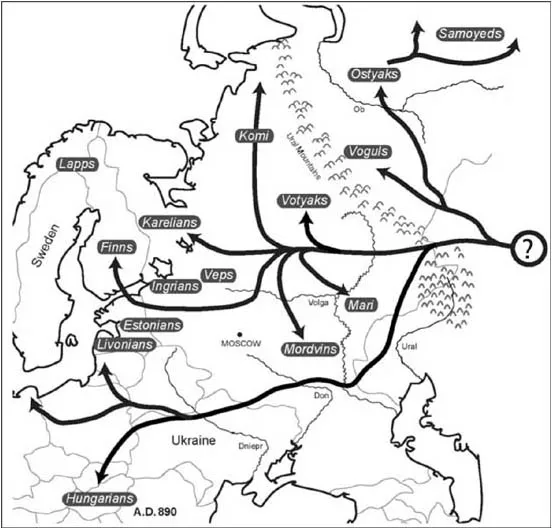

The Settlement Continuity Theory

Although there is adequate evidence to confirm the arrival of the Baltic Finns (including the Estonians) in the Baltic area about three thousand years ago, scientific advances in research suggest that this was by no means the beginning of settlement in Finland. Not only were these groups latecomers to Finland’s shores but also they may not have been the first Finno-Ugrians to arrive, either.

FIGURE 2.2 The Settlement Continuity Theory

To set the scene for the Settlement Continuity Theory, we have to roll back not only centuries, but millennia. We are aware of three great ice ages in Europe, but we need focus only on the last Glacial Maximum, when all of northern Eurasia was covered by a mighty ice sheet from 23,000 to 19,500 B.C. Northern Europe in its entirety, certainly including Finland, was uninhabited at this time. When the Nordic ice finally retreated after 19,500 B.C., the mammals and birds followed it northward, as conditions permitted. The humans advanced north again, slowly and unevenly. Who were these humans of twenty thousand years ago? What was their culture and language(s)? Were they Proto-Uralians, Proto-Indo-Europeans, or other ancient groups?

Our answers to most of these questions are inevitably incomplete, although we learn more as time goes by. We know, however, that the ice, retreating at a speed of about twenty-five kilometers a generation, started to render southern Finland ice-free around 9000 B.C. The southern half of Finland was populated by 8000 B.C. and northernmost Finland by 7500 B.C. Again, the question is posed: Who were they? What was their language/culture?

An Interesting Rendezvous

When the improving climatic conditions enabled our hardy vanguard of north-pushing Finns to begin to colonize the northern extremity of Finland around 7500–8000 B.C., they may have been surprised to meet another group who had arrived in northern Fennoscandia as early as 9000 B.C. from what was then an ice-free region between the British Isles, Denmark, and southern Norway. Although inland Scandinavia was still under an ice sheet, the Norwegian coast was ice-free, enabling the coastal groups to reach the Arctic. The coastal groups formed a mingling community of Saami (Lapps) and northern-bound settlers who between them established a Proto-Uralic tongue as the language of the area. Recent biological evidence shows the Lapps to be genetically very distinct from Scandinavians and Baltic Finns, but such a mingling around 7500 B.C. would explain how Lapps and Finns, though genetically distant, speak closely related languages. One of the groups most likely assimilated the other (although we cannot rule out the possibility that all the relevant linguistic elements were Proto-Uralian).

At all events, Proto-Uralian or Finno-Ugrian ancestral tongues led to Finnish being established, along with its dialects, in the expanse of land between the Gulf of Bothnia and Lake Ladoga. Why, then, should we quarrel with the basic logic of the Migration Theory, which linguists were satisfied with for over a hundred years? If Finns speak a language that is unquestionably Asian, why should we doubt their Asian provenance? Because genetic markers tell us otherwise.

The G...