- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Free Speech: All That Matters

About this book

What is free speech?; Why does it matter? These are pressing questions. In this book, Alan Haworth outlines and analyses the main arguments philosophers have advanced over the centuries, in an attempt to answer them clearly. He emphasises the strengths but also the weaknesses of those arguments, demonstrating that an understanding of both is essential if one is to to grasp the true nature and value of free speech. The contemporary debate over free speech tends to be clouded by rhetoric. Against that, Haworth stands back and takes a cool look at the issues. This book comes down on the side of clarity. It is an essential primer on an important topic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Free Speech: All That Matters by Alan Haworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Human Rights. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Questions of definition

My aim in this chapter is to describe the problems any credible attempt at a defence of free speech must aim to solve. It is, as I said, a ‘survey of the terrain’.

Let me begin with a few statements of the obvious. I shall take it that …

1 To exercise the right to free speech is perform an act of a certain type.

2 There is a moral right to free speech if people ought – morally ought – to be free to perform acts of that type.

3 There is a legal right to free speech if certain acts are afforded special legal protection on the grounds that they instantiate the exercise of the right to free speech.

4 In the ideal situation, legal principle will reflect moral principle. In other words, the acts people morally ought to be free to perform (statement 2) will be protected by the relevant law (statement 3).

If those assumptions strike you as so obviously true that they are hardly worth stating, so much the better. Any argument which aspires to be taken seriously is helped if it can start out from premises which it would be wilfully perverse to deny. Unfortunately though, these statements don’t get us very far. One reason is this: There are many acts – acts involving speech – which it would be hard to count as instantiating the exercise of free speech, at least, there is no seriously credible interpretation of that right from which it would follow that they count as such.

Consider:

• You lock yourself in a room, make sure that no-one can hear you, and proceed to read extracts from your favourite text out loud.

• You take a spray can and decorate walls with inane slogans – ‘I LIKE GIRLS’ and ‘KERMIT LOVES MISS PIGGY’.

In the former case, while you may be described as exercising the right to do as you please in the privacy of your own home, it would be wrong to say that, in so doing, you are also exercising the right which people normally have in mind when discussing free speech. For one thing, because you speak to no-one, and because nobody can hear you, your action lacks the publicity by which the genuine exercise of free speech is characterized. In the second case, your action appears too pointless and trivial to merit special protection.

With all that in mind, let us now turn to the following question: For what reasons might an act involving speech nevertheless fail to qualify for legal protection on the grounds that it is an exercise of the moral right to freedom of speech?

In recent times, answers to it have tended to focus upon offensiveness with some arguing that the right to free speech should be limited when it becomes offensive to this or that group, and others that, for example,‘there is no right not to be offended’. Controversies over offensiveness can become emotionally charged however – so much so that it can be difficult to appraise them impartially. If we are to gain a clear picture, it would be better to start elsewhere. Accordingly, I will begin with the triviality by which so much published material is characterized. I will then turn to pointlessness, and move on to offensiveness only after that.

Triviality

The following passage is drawn from the pages of OK, a magazine which describes itself as ‘no.1 for celebrity news’.

CINDY’S STYLISH PIZZA CHEF: Supermodel Cindy Crawford has revealed what really happened the day Harry Styles popped round to her house to make pizza for dinner. The 47-year-old star is surely the coolest mum on the block after the One Direction singer, 19, showed up at her Malibu pad to give tips to son Presley, 14, and daughter Kaia, 11.

The passage typifies a certain style of ‘celebrity gossip’ journalism, and I have selected it, only for its representative character. OK regularly carries several equally trivial stories, as does its rival publication, Hello magazine, and as do most ‘red-top’ tabloids in a typical week. So, can it be argued that there is a moral right to free speech such that OK’s freedom to publish this type of material should be legally protected? I think it would be hard to do so. The story is so trivial.

Points to note here are these: First, I am not suggesting that OK should be censored or suppressed. Its triviality may render it ineligible for special protection but, by the same token, neither is there any good reason for banning it. Second, I am taking it that, where there is a right to perform actions of a certain type, there are reasons for protecting the freedom to do those actions, even when there are good, ‘countervailing’ reasons for suppressing that freedom. That is part of what it means to say that there is a right. As the point is sometimes put, it is a feature of rights that they ‘trump’ those other considerations. The point will be familiar to anyone acquainted with contemporary political philosophy. It is more than ‘merely academic’ however, for appeals to ‘national security’, ‘economic efficiency’ and similar invocations of the public good are just the reasons to which governments do tend to appeal when seeking to suppress dissent. Considered in isolation, these may be perfectly good reasons, and not easily dismissed. We need to know what grounds there may be for protecting speech, even when they can be persuasively invoked.

By way of illustration, compare OK’s Cindy Crawford story with the reports, first carried by The Guardian and the New York Times in 2013, that the USA’s National Security Agency is engaged in wholesale surveillance (aka ‘The Snowden Affair’). In defence of the latter it might be argued, for example, that the citizens of a democracy have a moral right to be kept informed of their government’s activities. No such considerations exist in the case of the Crawford story. The main reason for describing it as ‘trivial’ lies in the absolute ordinariness of the events it narrates. It must happen every day that hundreds of thousands of women invite some local teenager to have tea with their own teenage children and, if these events go unreported, that must certainly be thanks to the fact that no one except the parties directly involved is likely to take the slightest interest in them. The OK story is only notable for the fact that it concerns ‘celebrities’ – a supermodel and a member of a popular boy-band. Otherwise it would be of no consequence at all.

Well-known platitudes are lurking here, so let me put it this way: Suppose that, for whatever reason, Cindy Crawford were to object to OK’s having published the story about her tea-time invitation to Harry Styles. (I have no idea what that reason might be, but that’s irrelevant.) Suppose that she were to go so far as to take OK to court. Now suppose that OK were to enlist Voltaire in its defence. (I don’t mean the real Voltaire. I mean the apocryphal Voltaire – the Voltaire who is alleged to have said, ‘I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it’.) Imagine Voltaire standing up in court and saying, ‘I disagree with OK’s statement that Harry Styles popped round to Cindy Crawford’s house to make pizza, etcetera, but I will defend to the death … etcetera.’ (To the death, mind.) You only have to picture this Monty Pythonesque scenario to appreciate its absurdity. There being nothing more to the story, there would in fact be no good reason for dismissing Ms. Crawford’s objection to the invasion of her privacy. Moreover, and though it might appear so at first glance, nor is my story as frivolous as all that, for – in fact – the popular press frequently does commit invasions of privacy, against the wishes of its victims, merely in order to satisfy a public taste for tittle-tattle. The example raises the question of how, in the absence of a plausible ‘free speech’ justification, it can possibly defend such activities.

I disagree with what you say ….etc.: The famous line was first attributed to Voltaire in a biography, The Friends of Voltaire, written by Evelyn Beatrice Hall (aka S.G.Tallentyre) and published in 1906. There is no evidence that Voltaire himself ever said any such thing.

Again – to take another popular truism – given that OK’s story is, no doubt, true, and supposing that there are top-flight politicians, captains of industry, judges, generals and the like who sometimes pass their time leafing through the pages of OK – and for all we know there may well be – then it will be equally true that OK ‘speaks truth to power’. It is sometimes said to be the duty of the press to do just that – but in this case, so what? It’s impossible to believe that a knowledge of Ms Crawford’s invitation to Mr Styles could possibly affect the policies initiated by such individuals, either for good or ill. It follows, again, that it would be disingenuous if OK were to invoke a ‘right to free speech’ in support of its publication of the Cindy Crawford story.

Finally before moving on, I should recognize that my argument is potentially open to a ‘slippery slope’ objection. It’s an objection which, I am sure, some readers will be wanting to raise and it states that, while OK-style celebrity gossip may be trivial, it forms a small part of something larger and more significant. Perhaps they will urge that a free press is a bastion of a free and democratic society, and that any attempt to silence the press – even an attempt to suppress a minor item of celebrity gossip – threatens to undermine the institution as a whole. In short, they may want to invoke a ‘slippery slope’ argument.

But such arguments are rarely persuasive. Consider the following.

Argument One:

1 I have now eaten my sandwich. I think I’ll throw the wrapper into the street.

2 But, if I were to do that, others might follow my example – it would be the beginning of a slippery slope – and if everyone in the vicinity were to throw their waste paper into the street, the street would be covered in litter. Everything would be a complete mess.

Therefore,

3 I had better not throw the wrapper into the street.

Argument Two:

1 I should like to drive from London to Brighton this morning.

2 But, if I were to do that, others might follow my example – it would be the beginning of a slippery slope – and if the entire population of London (about eight million) were to choose, just now, to drive to Brighton, there would be a massive traffic jam, terrible pollution and nobody would get anywhere.

Therefore,

3 I had better not drive to Brighton.

Argument Three:

1 (Said by a judge): I should like to uphold Ms Crawford’s claim against OK magazine.

2 But, if I were to do that it would be the beginning of a slippery slope, the freedom of the press would be so threatened that our free and democratic society would be in serious jeopardy.

Therefore,

3 I had better not allow Ms Crawford’s claim against OK.

It should be clear that, in each of the above cases, the credibility of the argument hinges upon the likelihood that the state of affairs envisaged at step two will actually transpire. It is, thus, only too well-known that, where one person litters carelessly, others are encouraged to follow suit, which means that Argument One supplies quite a good reason for not throwing one’s sandwich-wrapper into the street. By contrast, it is vanishingly improbable that the entire population of London will decide to drive to Brighton at just the same moment. It follows that Argument Two is thoroughly unpersuasive. Likewise, in the case of Argument Three – which is the objection at issue – to find it persuasive you would have to believe that nearly everyone who has ever featured as the subject of a piece in OK is likely to object and, further that, were this to happen, the fabric of our free, open and democratic society would be seriously threatened. None of this is at all likely or credible.

Pointlessness

In the course of a well-known judgment, the American Supreme Court judge, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, said this.

The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.

Actually, Wendell Holmes’s judgment is well known, mainly for having been cited so often by philosophers and legal theorists in their discussions of free speech. That’s why we shall also have to consider any lessons it may turn out to contain.

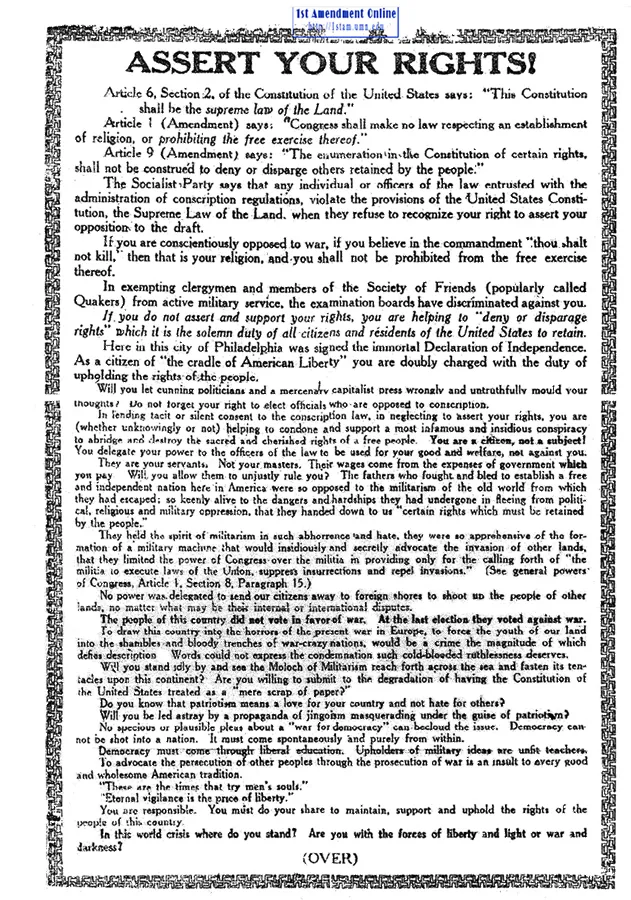

Notice, then, that Wendell Holmes’s remark is open to two different interpretations. On the one hand, you could take him to be asserting that the restriction of free speech may be justified in times of danger and national emergency. On this point, it’s relevant to note that he was speaking in 1919, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- About the author

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Picture credits

- Introduction

- 1 Questions of definition

- 2 Free speech and truth

- 3 Free speech and democracy

- 4 Free speech, time and change

- 100 Ideas

- Texts cited

- Copyright