![]()

1 Introduction

The Germans are an enigma not only to the rest of the world but also to themselves. Why does a society that prizes security and order and that seems to have a rule for everything not set a speed limit on its superhighways, despite the increasingly high number of automobiles that use these roads? How does such a heavily regulated society manage to attain such economic success in the competitive global market? How could a culture that produced such inspired musicians and artists as Bach, Beethoven, Goethe, and Schiller and such profound philosophers and scientists as Kant, Hegel, Heisenberg, and Einstein fall prey to the barbarities of the Nazis? How can a people be so sentimental, loyal, and trustworthy on the one hand and be so arrogant and easy to dislike on the other? These are only some of the questions that people pose when they try to understand the Germans. But foreigners are not the only ones who have that difficulty.

Libraries and bookstores in Germany are filled with works attempting to answer these and other questions. Germans spend great amounts of time among themselves discussing their puzzling heritage and culture. In fact, as will become evident in chapter 4, discussing almost anything is one of the Germans’ favorite pastimes. And trying to answer the question “What does it mean to be German?” is one of the more common topics in these discussions.

A legendary German hero offers some initial clues to this challenging puzzle. In the Teutoburger Forest near Detmold stands a huge metal statue of Hermann the Cheruscan, whom Roman historians called Arminius. According to history and legend, in A.D. 9 Hermann led the Cheruscans and other Germanic tribes in their crucial victory over the three Roman legions that were trying to conquer the territory which we have come to know as Germany. After this defeat, the Romans never again tried to invade the Germanic territories.

We know of this battle first because it was recorded by the Romans and second because it passed into legend among the Germanic tribes, who were an oral people. It resurfaced in the works of German authors and thinkers after the Middle Ages. But not until the nineteenth century did the romantic and nationalist forces choose to resurrect the legend as a symbol of the greatness of the Germanic peoples and their culture. During this period the huge, heroic statue of Hermann was constructed and his legend promulgated in German schools. And it was during this same period that Germany was united as a modern nation-state. Here we find a major piece in the German puzzle: why did it take this two-thousand-year-old culture until 1871 to finally coalesce into a modern nation?

The spread of the Hermann legend and the building of the great statue were outward symbols of a struggle for the construction of a national German identity and a modern German state. As such, they served as an antidote to the sense of insecurity and inferiority which has marked much of German history. This sense of insecurity was derived in part from Germany’s geographic position, which often led to the Germanic kingdoms serving as battlefields where other European states fought their wars. It arose from watching other peoples—French, British, Spanish—form centralized states and create huge empires and great civilizations while the Germanic states remained fragmented, with little political and economic clout. The Germans, divided into hundreds of small kingdoms, duchies, and principalities, felt themselves to be less than important in the grand scheme of Europe and the world. This lack of identity and sense of inferiority partly explains the preference of many of the German nobility for speaking and writing Latin during the Middle Ages and then French in later periods. It also prompted Emperor Charles V to say that the German language was only fit for speaking to horses.1

Today this feeling of inferiority lingers among the Germans. The atrocities of the Third Reich have only served to make it more difficult than ever for Germans to identify themselves as such. It is telling that many young Germans have little or no knowledge of their Germanic ancestors. When asked, they often don’t even know who Hermann the Cheruscan was. And when queried about their ancient Germanic ancestors, they will usually say that they were a primitive and barbaric people who were neither literate nor capable of creating the infrastructure which made Rome such a great civilization. Given this negative prejudice toward their own ancestors, it is striking that among the New Age movement in Germany there are numerous Germans who are fascinated with Native American cultures. While traveling through Germany, you can occasionally catch sight of an Indian teepee in someone’s backyard. You will also hear of groups of people gathering in sweat lodges or participating in other Native American religious rituals. It is ironic that Germans can be so fascinated by Native American cultures but have no interest in their own, when both cultures had so much in common—politically, culturally, and spiritually.

Many of us think we know quite a lot about the Germans. After all, we argue, they are not so different from us and they played a large part in our own history. More Germans immigrated to the United States than any other ethnic group, and approximately fifty million American citizens currently claim to be at least part German.2 But our views of Germans are often skewed, especially by the media. Of course we know of the beer-drinking Germans in their traditional costumes at the Oktoberfest, and we know Germans make great cars, but the Nazi image is omnipresent for many Americans, even if only in the background. What would Indiana Jones have done without the Nazis to fight against? And how many of the villains in Hollywood films have had a German accent or worn uniforms similar to those of the Nazis?

Many of these images have become classic stereotypes, and as such they influence our perceptions, thoughts, and behaviors when dealing with Germans. The insidious thing about such stereotypes is that they often have a core of truth, which is then applied indiscriminately so that every German becomes like the stereotype. In addition to the loss of individuality that such pigeonholing brings with it, there is usually an implicit emotional judgment about the stereotype, which makes successful communication difficult.

The reader is advised to remember that Germany is a densely populated country of over eighty million people who exhibit considerable diversity, which includes regional differences and dialects, educational and class differences, and political and ideological differences. Like so many European countries, the spectrum of political thought and party allegiance in Germany is far wider than that found in the United States. A typical German will notice little political diversity in the United States and view the Democrats and Republicans as representing two flanks of the same party. Americans have little to compare with major political positions taken by the Social Democratic Party (SPD) or the Green Party, and this is significant in understanding the German worldview.

In this book I have attempted to find the broader, underlying patterns of German life and culture. In doing so I often talk about “the Germans” and “the Americans,” realizing full well that such generalizations can slip easily into stereotypes. Generalizations are useful, however, when trying to describe the overall form and structure of the forest without getting lost in the individual trees.

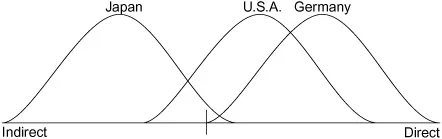

An illustration will make this clearer. While identifying Asian cultures as indirect has become a popular cliché, researchers have discovered there are differences in levels of directness among European cultures as well. Americans often pride themselves on how they “like to get to the point” and how they don’t waste time “beating around the bush.” From this perspective, the indirectness of Asians and their preoccupation with giving and saving face seems confusing and tedious, if not downright dishonest.

It thus comes as a surprise to many Americans to discover that the Germans are even more direct and less concerned about face issues than Americans are. As will be shown in the chapter on communication styles, this difference can cause significant problems when Americans and Germans try to communicate. Thus, while it makes sense to talk about the degree to which Germans and Americans are similar in their directness, in reality we find a great deal of difference in directness between these two cultures. There are some Americans who are blunter and more direct than most Germans, and there are some Germans who are very indirect. But this does not make the overall generalization any less valid if we assume that there is a normal distribution in both groups regarding this trait. Illustrated graphically, this distribution resembles three overlapping bell-shaped curves:

Note that while both peak on the right-hand side of the continuum between indirectness and directness, the American peak is a little closer to the indirectness pole than the German. The peak, of course, is where you find the predominant pattern of behavior in that culture. Finally, note how much further the Japanese are toward the indirectness extreme than either Germans or Americans.

A last point: to avoid confusion and offense, let me explicitly state that when referring to “the Americans,” I am speaking about the predominantly white, middle-class, mainstream culture within the United States. This is not to disavow the importance and richness of cultural variety within the U.S., but only to help draw a broad and easy-to-understand picture for the purposes of comparing and contrasting the two cultures.

![]()

2 Who Are the Germans?

Germany is a complicated country, a fact the Germans themselves are first to acknowledge. To talk simplistically about German culture is to engage in verbal sleight of hand. The very idea of “German culture” is ambiguous because it can be understood on several levels. Do we mean the culture of the relatively young German nation, whose borders have changed several times in the last hundred years, or do we mean the culture of all the German-speaking peoples? The latter would have to include the Austrians, the great majority of the Swiss, and isolated groups of Germans as far east as the Volga and as far south as the Seven Mountains region of Romania, not to mention the German-speaking people in AlsaceLorraine and Luxembourg.

For the sake of clarity, when used in this book Germany and Germans will refer exclusively to the Federal Republic of Germany and its citizens. But even by limiting this examination to the current culture of the Federal Republic of Germany, a surprising amount of complexity still remains. Although Germany is small by American standards—its total area is less than that of Montana—the diversity and complexity of this country are not to be underestimated. Understanding this complexity is a key to working, living, and communicating successfully with the Germans.

Modern Germany can be likened to a patchwork quilt that has been carefully sewn together from scores of different little kingdoms and principalities. To understand how this came to be and what its current consequences are, we must take a brief look at its history.

The Essentials of Modern German History

Americans are a forward-looking people who tend to orient more to the future than the past, and for that reason I have tried to keep the section on German history short. But it is useful to note that Germans take a different approach to history than do Americans. They tend to always look to historical precedents in order to understand the present, a perspective followed to some extent in this book. I often use German history as the context for the present. For that reason, it is wise for Americans to spend some time learning more about Germany’s past.

Although many Americans show little interest in understanding or talking about history, this attitude is counterproductive when dealing with Germans. As will be described in greater detail in chapter 4, conversing and, in particular, engaging in detailed discussions are favorite national pastimes in Germany. Educated Germans have been raised to think and analyze historically; the American who learns the rudiments of this way of thinking and talking will earn respect and credibility from them.1 Not to do so is to run the risk of being written off as simply another uneducated American who is ignorant of the more important things in life.

The English word Germany derives from the name Germanus, given to the people of this territory by Tacitus, an ancient Roman historian. Tacitus was quite taken by these early, seminomadic “Germanic” tribes, seeing in them a healthy, more natural way of life that he hoped would be an antidote for the decadence of the Roman Empire. The interesting fact is that none of these tribes called themselves “Germans.”

After playing a major role in the downfall of the Roman Empire, these tribes were conquered by Charlemagne and converted to Christianity. Both the French and the Germans claim him as a national hero, but to the French he is Charlemagne and to the Germans, Karl der Große. Charlemagne was responsible for forcibly converting the last of the Germanic tribes to Christianity, and he also became emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in A.D. 800, uniting most of western and central Europe.

Within decades after his death, however, this empire began fragmenting politically, a process that continued for centuries. This was further encouraged by the religious wars following the Reformation. Fragmentation was to a large extent the result of Germanic laws of inheritance, which divided a man’s property equally among his sons, in contrast to other European countries, where, under primogeniture, property passed in toto to the eldest son. Consequently, what would become Germany remained a weak network of small warring states rather than a strong centralized country like France, England, or Spain. In fact, in 1648, with the signing of the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years War, what would later become united Germany was then a jigsaw puzzle of approximately three hundred small autonomous kingdoms, duchies, principalities, and free cities. It was Prussia’s destiny to change this.

Imperial Germany (1871–1918)

At the time of the Peace of Westphalia, Prussia was a small, unimportant kingdom located near present-day Berlin. But through a series of strategic wars, it expanded both its territory and power. Like Catholic Austria to the south, Protestant Prussia had designs on full control over the other German-speaking states. After a series of wars in which first Denmark, then Austria, and finally France were defeated, Prussia gained control over the German-speaking states, except for Switzerland and Austria. In 1871, under the leadership of the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the German Empire was created, finally bringing about a unified Germany. Bismarck supported and guided the Industrial Revolution in Germany, helping this newly centralized state rapidly become a modern world power. Prussia’s dominance left its mark on Germany in many ways, not the least of which is the fact that Berlin became the political center of modern Germany.

Like much of Europe, Prussia was organized according to a rigid hierarchy, which was basically a type of caste system. This class system was a direct outgrowth of European feudalism, an impediment against the democratic forces that were gaining strength throughout the continent and one of Bismarck’s greatest political challenges. To deflate the growth of democracy and socialism, Bismarck created Germany’s social insurance system, which is still in effect. This system serves as a major foundation for the social market economy that underpins German society. It is a major cultural component which reflects the Germans’ traditional acceptance of the role of the guardian state and the consequent deemphasis on individual freedom. While many of Bismarck’s policies had positive effects, which are still evident, his foreign policies, in particular his humiliating defeat of the French in 1871, set the stage for Germany’s traumatic experiences in this century.

Many Americans are under the impression that Germany is solely responsible for starting World War I. This view ignores the complexities of European politics at the turn of the twentieth century. European countries were involved in a series of “entangling alliances”—some of them the result of Bismarck’s policies—and thus were poised on the brink of war for several years before its actual outbreak in 1914. Experts agree that if the war had not started because of Germany’s support of Austria (which declared war on Serbia), another trigger would have been pulled by the European powers to start the war they were all preparing for. In the end, Germany’s loss of this war gave France the opportunity to avenge itself for its defeat by the Prussians.

Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

After Germany’s defeat and with American consent, the French and British governments declared Germany to be solely responsible for the outbreak of the war and imposed huge war reparations. This strategy was designed to cripple the economy and ensure that Germany would remain a second-rate power. After the enormous hardships and great personal sacrifice during the war years, the loss of World War I was a great blow for the Germans and had repercussions throughout the country. In November of 1918, as the war drew to a close, the German emperor, Wilhelm II, abdicated and fled the country. The official class system collapsed, and political views became polarized. Radical forces of both the left (communists and socialists) and the right (nationalists and monarchists) were armed and intent upon installing a government of their own choosing. These forces clashed violently in the larger cities, and civil war seemed about to engulf the nation.

During this period, a more moderate, democratic government was installed in the German city of Weimar. Elections were held, but while much of the outright street violence abated, political assassinations continued. The huge war reparations payments, designed to economically bleed the country, proved effective. Hyperinflation ravaged Germany, and, at its peak, prices doubled daily, creating further hardship and turmoil among the German populace.2 Lifetime savings were wiped out overnight, and the economy collapsed, creating devastating unemployment. Finally, just when Germany seemed to be regaining some economic control, the stock market crashed in New York, setting off a worldwide economic depression.

This depression threw millions of Germans out of work and again set the stage for the emergence of small, radical political parties that could not agree on a common economic or political solution to Germany’s problems. It was during this time that right-wing radicals reemerged and made their successful bid for power. By 1933 these radicals, in the form of the National Socialist German Workers Party (the Nazi Party), had gained control of government.

The Third Reich (1933–1945)

Just how much popular support the Nazis and their ideology actually received from the German populace is still a matter of controversy and emotional debate. What is beyond doubt is that the majority of Germans ...