![]()

1 Introduction

Welcome to the matrix, where multiple bosses, competing goals, influence without authority, and accountability without control are the norm. It is a world where skills, not structure, are the drivers of business and personal success.

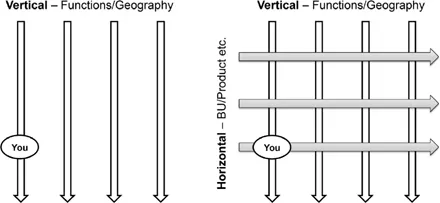

At its simplest, a matrix reflects the reality that work no longer fits within the traditional “vertical” structures of function and geography. Today, work is much more “horizontal”: it cuts across silos and even extends outside the organization to include suppliers, customers, and other business partners.

Most large organizations now operate some kind of matrix organizational structure in order to serve global customers, coordinate international supply chains, and run integrated internal systems and business functions.

In a matrix, we routinely work with colleagues from different locations, business units, and cultures in cross-functional and virtual teams. Matrix working is now everywhere – and it requires different skills in leadership, cooperation, and personal effectiveness.

Figure 1.1 From vertical to matrix working

MATRIX ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES

Matrix management is not the latest management and consulting fad; it has been around since the 1970s. As soon as organizations have multiple locations, countries, or business units that require coordination, some form of matrix evolves, even if only at group level. As organizations become more integrated and share systems, resources, or talent, the matrix evolves so that it reaches deeper into the organization.

Structure should always follow strategy. The four key advantages that organizations seek when introducing a matrix structure are:

To break the silos: to increase cooperation and communication across traditional vertical silos and to unlock resources and talent that are currently inaccessible to the rest of the organization.

To deliver “horizontal work” more effectively: to serve global customers, manage supply chains that extend outside the organization, and run integrated business regions, functions, and processes.

To be able to respond more flexibly: to reflect the importance in the structure of both the global and the local, the business and the function, and to respond quickly to changes in priorities.

To develop broader people capabilities: a matrix helps us develop individuals with broader perspectives and skills, who can deliver value across the business and manage in a more complex and interconnected environment.

The business logic is compelling, but introducing a matrix does mean a step up in complexity in the way people work together and many organizations have struggled with implementation. Some even claim to have abandoned the matrix (although in reality they usually just move to a simpler form). The disadvantages they cite include:

Delays in decision making (too many people getting involved).

Increase in bureaucracy (a proliferation of meetings and committees).

Increase in uncertainty and conflict.

Both the advantages and disadvantages of the matrix are fundamentally about people and the way they work together. Delivering the advantages and avoiding the disadvantages cannot be achieved through a structural change alone, only by building the skills and mindset necessary to cut through the complexity.

A DAMAGING PREOCCUPATION WITH STRUCTURE

Organizations that ignore skills and seek a structural solution on its own can remain stuck in an endless cycle of reorganizations, which not only fail to solve the problem, but make it worse by disrupting the networks and relationships that really get things done.

In my work with over 50,000 people in 300 major multinationals in more than 40 countries, I have learned that structural change solves nothing, and that an excessive focus on structure has been positively damaging to the development of matrix management. Much more important are the networks, communities, teams, and groups that form within a matrix to get things done. Structural change is a blunt, slow, and imprecise tool for forcing change:

It leads to the structure going too deep into the organization. A matrix structure usually only adds value for two or three senior to middle management layers. For the 85 percent or more of people who have purely local jobs (even in the most global organizations), the matrix is likely to cause unnecessary complexity.

It leads to endless reorganizations. Because we are looking for a structural solution to a problem that can only be solved through different skills and ways of working, we keep tinkering with the structure in the vain hope of success.

It leads to a lack of emphasis and underinvestment in building the leadership, collaboration, and individual skills that are vital to make the matrix work.

Skilled people can make almost any structure succeed, but even the most elegant structure will fail if the people within it do not have the skills to make it work.

DELIVERING STRATEGY REQUIRES SKILLS

Effective organizational change flows from strategy to structure to systems to skills. All four waves of change need to be completed and aligned in a successful matrix implementation.

Once organizations are clear about their strategy, they can then focus on the formal structure and the high-level people moves necessary to make their goals happen.

At the same time, many organizations begin a necessary but expensive and time-consuming journey toward common systems. A full-scale SAP, Oracle, or Microsoft Business implementation can take several years and have a major, organization-wide impact on business processes such as product lifecycles, customer relationship management (CRM), supply chain and human capital management. In a large, global organization a full SAP implementation may take five years or more. Depending on the size of your business, and including employee costs, such an implementation could cost tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars.

Nevertheless, many organizations do little beyond announcing the structural changes, and fail to consider how to build the skills to cope with this higher level of complexity. Insufficient thought is given initially to changing criteria for selection and promotion, rewards, capabilities, and training and development to reflect the new environment.

A successful matrix implementation requires the embedding of strategy, structure, systems, and skills. A failure to manage change in any of these four areas can lead to a failure of the overall implementation.

In my experience, many organizations invest heavily in structure and systems and neglect the development of skills. When people find it difficult to operate the matrix, they may blame the structure and reorganize again, instead of realizing they lack the necessary skills.

A SHIFT IN POWER FROM STRUCTURE TO SKILLS

Because authority and power are shared between multiple bosses in a matrix, they become less effective as ways of getting things done. Individuals with multiple bosses have to manage tradeoffs and make decisions about where to invest their time and enthusiasm. Managers can feel as if they have lost the authority and control they had in the simpler, functional, single-manager structure of the past.

Two common complaints from managers new to matrix working illustrate this concern:

“How can I be accountable for something I don’t control?”

“How can I get things done without authority?”

I will introduce some tools and concepts for dealing with these challenges later, but for now let’s think about the implications of these statements. Are these managers really saying that they cannot get things done without direct control and hierarchical authority?

We call the people who raise these objections “matrix victims.” Their resistance is often rooted in a lack of confidence in their skills and capability to get things done without traditional control and authority.

In a modern organization, with skilled people, an overreliance on control and power can in fact be counterproductive. It can create unwilling followership at best and is more likely to provoke disengagement, resentment, and avoidance. A hierarchical and control-based individual or corporate culture will really struggle to make a matrix work.

During the implementation of a matrix organization, companies such as IBM and Cisco reported losing around 20 percent of their managers through a combination of structural change and turnover of those who did not fit the new way of working. Most organizations see this turnover as an essential part of bringing about the necessary change in style and embedding matrix behaviors. If your leaders are overreliant on hierarchy and control, they may not be suitable for managing in the matrix.

This shift in power from the structure of the past to the shared authority and more complex skills of the matrix does not go unopposed. Despite the reality that work has become more horizontal, many organizations have struggled to break the power of vertical silos. Traditionally, authority, control, and power rested in vertical functional and geographic silos; and they still provide the route for career progression for most people. Consciously or unconsciously, powerful vertical managers may resist the loss of power to horizontal processes and reporting lines.

THE EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT UPSIDE

While the move from structure to skills can be uncomfortable for managers, it can provide a significant upside in employee engagement, critical in all organizations. High levels of engagement increase “discretionary effort,” meaning that people are prepared to go the extra mile to achieve their goals. Greater engagement correlates with high levels of performance, retention, and learning.

Matrix structures often get a bad press for increasing complexity and even conflict, but they do allow us to engage some powerful drivers of employee engagement.

This book will show that matrix success requires individuals to take more ownership of their goals and roles; creates broader and more meaningf...