![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURES IN EUROPE![]()

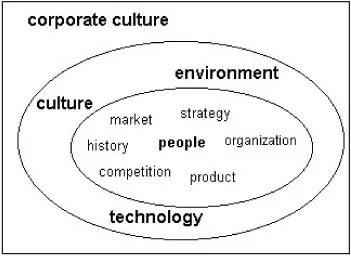

The Culture Triangle

Culture is a system that enables individuals and groups to deal with each other and the outside world. Think of it as a spiral. At the heart of the system are shared values and beliefs and assumptions of who and what we are. They manifest themselves in our behavior and language, the groups we belong to, the nature of our society. They are further externalized in our artifacts, our art and technology, the way we deal with and change the physical world. The system also works from outside in. Our physical environment conditions our technology and art, our behavior and language, and so on to the heart of our identity.

Culture is a living, changing system that embraces our personal and social life. Everything we do or say is a manifestation of culture. There is no aspect of human life, from the way we say good morning to the rockets we build to go into space—or bomb our neighbor—that is not culturally conditioned.

There are three points to make about this model:

Whatever culture they belong to, everyone does what works best for themselves and their group. American, German, and Japanese companies make cars that are virtually indistinguishable, yet the cultures that produce them are very different. The only success criterion of a culture is how effective it is in ensuring its survival and prosperity. No culture is intrinsically “better” than any other.

No culture is static. It turns like our spiral. As the rim of a wheel turns faster than its axle, the values at the heart of a culture change more slowly than the technology at the edge, but they still change. And if something changes it can be directed.

The way people behave is not accidental or arbitrary. The external characteristics of culture, from its superficial etiquette to its architecture, are rooted in its hidden values and beliefs. If the externals need to change then so must the values, and vice versa.

As well as debating what culture is, it is also interesting to look at what culture does. Whether it is national or corporate, culture is a mechanism for uniting people in a common purpose with a common language and with common values and ideas. It can liberate and empower individuals with a sense of self that transcends their own singularity. Or it can create prisoners of a culture no longer appropriate for its time and circumstance, which isolates its members and threatens those outside it.

Corporate cultures are determined by the interaction of parent culture, technology, and the external environment. Again, these are never static and can therefore be directed; there is no “right” culture, only a successful one; and the externals are rooted in deep underlying values.

When people from different nationalities or cultures come together in teams, meetings, negotiations, or as employees of the same company, they bring with them different expectations and beliefs of how they should work together. They have different concepts of what an organization is, how it should be managed, and how they should behave within it.

Cultures of all kinds are invisible until they encounter others, when the differences become apparent. The least dangerous differences are the obvious ones—we notice them and can make adjustments. The dangerous ones are those that lie beneath the surface. In a corporate environment beliefs about the role of the boss, the function of meetings, the relevance of planning, the importance of teamwork, or the very purpose of an organization are often taken for granted among colleagues. Yet they can be very different even among close neighbors. Outward similarities between European business goals can conceal real differences in how they should be realized.

The way others do things is not different out of stupidity or carelessness or incompetence or malice, although it may appear so. Most people do what seems right at the time. The judgment of what is right is rooted in habit, tradition, beliefs, values, attitudes, and accepted norms; in other words, the culture to which that person belongs.

The purpose of this book is not simply to identify cultural differences. It is to identify which of those differences have a serious impact on the way we work together. It is based on a large number of anecdotes and impressions and judgments, ranging from the trivial to the profound. Not that the trivial is unimportant: It can be a source of constant irritation as well as a focus for much deeper frustration. Etiquette may appear trivial—whether to use first or last names, what to wear, how to behave at lunch or at meetings. However, if you get stuck on this superficial level of interaction it is hard to penetrate to a more satisfying level of understanding and cooperation.

“We are meeting to decide on an investment proposal. I put a lot of time into studying the reports before the meeting. It is evident that my British colleagues at the meeting are examining the papers for the first time. It wastes all our time but it doesn’t stop them giving their opinions.”

(Dutch engineer)

“My staff meetings are very annoying. It is hard to get them to stick to the agenda. And they insist on discussing every point until everyone has had their say.”

(French manager of an Italian company)

“You have the impression that the French don’t realize that they are at a meeting. They don’t pay attention or they interrupt or they get up and make a phone call.”

(English director of a Franco-British company)

In researching this book among managers, business issues like objectives or strategy or technology were rarely mentioned as areas of cultural difference; difference of opinion maybe, but not misunderstanding. Most of the difficulties occurred in day-to-day interaction between bosses and subordinates, members of the same work group, other colleagues. By interaction I do not mean the degree of formality or friendliness or other aspects of personal relationships, I mean the way people behave and relate to each other in a business context.

So what determines how people behave and how they interact? In what way do they differ from company to company and country to country? And, most important, which differences get in the way of working effectively together?

Three categories of behavior predominate: communication, organization, and leadership—the Culture Triangle.

Communication is centered on language, although it extends into nonverbal communication and other behavior that gives messages about our expectations and beliefs.

The other two categories relate to values. The first is a set of values about organization and the role of individuals within it. How is work organized? How do you forecast and plan? How is information gathered and disseminated? How do you measure results?

The second is a set of values about leadership. Who has power? How do they get it? How do they exercise it? What is authority based on? Who takes decisions? What makes a good boss?

There is a spectrum of belief in each of these dimensions and these combine to influence how people behave toward each other.

There are many other ways of classifying corporate culture and it is possible to break communication, organization, and leadership down into a number of elements. If the human brain were capable of assimilating them in a coherent picture I would bring them all together. Like any other oversimplified theory—and I have never come across a model of human behavior that is not oversimplified—this draws attention to what is omitted as much as what is included. It would be fatuous to claim that this, or any other model, is anything more than an aid to understanding. It is a working tool rather than an explanation.

BIRTH RATE

Which country has the highest and which the lowest birth rate?

Ireland

Turkey

Latvia

![]()

Communication

Language

The single most important competence in international business is the ability to make yourself understood and understand what others are trying to tell you. The rest is important, but not as important as this.

Language is the most obvious and immediate characteristic of another culture and the first barrier to overcome in understanding it. Almost everyone I have interviewed recommended that anyone embarking on a business or any other kind of relationship with someone from another culture should learn something about the language. This applies even if the other person speaks your language fluently or you are working in a third language. It is unlikely that you will ever be good enough to do business in the language or have a serious conversation. And if you do business in several countries those are impossible tasks. So why bother, especially if you speak English?

First of all, it is a courtesy to know at least some of the essential politeness words. Most people, especially if they speak a minority language, are pleased and flattered that foreigners make the effort, even if it is only a phrase or two. It is a sign that you do not take it for granted that they should speak your language and you appreciate the fact that they do. This is especially important if you are a native English speaker.

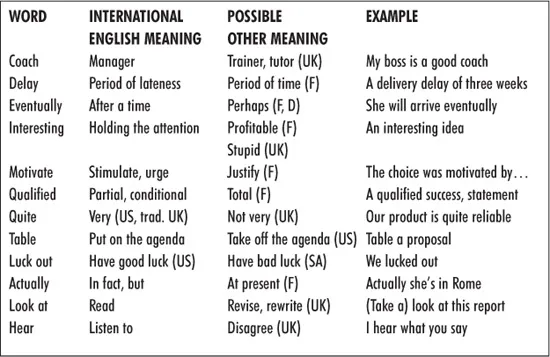

Secondly, an acquaintance with someone else’s home language helps you to understand them when they are speaking yours. If French speakers say “actually” or “delay” or “interesting” when they are speaking English, they may be using the words in the French and not the different English sense. When a Russian or a Chinese speaker answers “yes” in their own language to a negative question they are reinforcing the negative. For example, “Are you not going to sign the contract today?”—“yes” means that they are not going to sign it. “Are you not going to sign it?”—“no” means that they are going to sign it. When they are speaking English or another European language it is possible that they are keeping to their own usage. Such nuances are useful to know.

Thirdly, language is not only a vehicle for communication but gives an insight into a people’s ways of thinking, attitudes, and behavior. Much of our culture is handed down and disseminated through language. Look up “anglais” in a French slang dictionary and “French” in a similar English dictionary and you will sense the historical relationship of the two countries and the origin of the stereotypes that they have of each other. (In short, the English language associates the French with pleasure and sophistication, the French language associates the British with violence and boring food.) Knowing that Finnish does not distinguish between genders, that it has the same word for he and she, explains why Finns sometimes mix up pronouns when they speak English. Knowing that Chinese has no tenses, that verbs make no distinction between past, present, and future, may help understand Chinese concepts of time.

International English…

Some years ago I was hired by an American bank. I received a letter from the head of human resources that started, “Dear John, I was quite pleased that you have decided to join us.” That “quite” depressed me. I thought he was saying, “We’re kinda pleased but wish we had hired someone else.” A few weeks after I started work I discovered that in American English “quite” does not mean “fairly,” as it does in British English, but “very.” At about this time my American boss told me to “table” an idea I had. So I brought it up at the next staff meeting, to his extreme displeasure. In British English “table” means put on the agenda, while in American English it means take off the agenda.

The concept of the boss as “coach” is still in vogue. An analogy taken from sport, it is originally American training speak and has been adopted extensively in Europe. However, the role of the coach in American sport is very different from that in Europe. The team coach in the US is what in Europe is called the team manager, an authoritarian figure who is solely responsible for selecting and managing the team and frequently dictates the play. A coach in the UK has an entirely different role, that of trainer or tutor. I have seen an American boss and his British staff in complete agreement about the nomenclature of his role as coach but at permanent logger heads as to how he executed it.

The potential for misunderstanding increases with people who speak English as a second language. The English that they learn in the classroom as children is not the same colloquial language that native speakers use. International English has a simple vocabulary and a standard pronunciation. Native English speakers have a variety of accents, colloquialisms, and slang that foreigners find as difficult to understand as a Cockney does Glaswegian. At international meetings and conferences in English it is m...