![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Enter the Patterns

AN OPENING TOUR

Charge first into the Driver pattern—full speed ahead! Sit forward in your chair and bore your eyes into this page as though, like lasers, they could burn a hole through it. You might notice a sense of urgency (and blood pressure!) rising as your reading voice CLIMBS TO THE SHOUT OF A BATTLE CRY!

Too hot? Take a deep, slow breath and sit back, still straight in your chair with your feet flat on the floor, and place yourself squarely in the Organizer pattern. Hold this book for a moment at chest level, as if it were a choir book, and invite a moment of order and composure.

Too slow? Swing into the pattern of the Collaborator, which you can roll into by rocking in your chair—side to side, back and forth—letting your head go as well. Perhaps you notice a loosening feeling from the belly up, a great starting point for playing with the give and take of relationships or rolling with the punches.

Too silly? Let go and lean back in your chair, letting your eyes drift up to the ceiling; allow your peripheral vision to engage, seeing the whole room at once and nothing in particular. You’re hanging out in the pattern of the Visionary.

Too pointless? Go back to the Driver, and already you might notice a complementary relationship among these four distinct patterns. Taken together and used appropriately, they allow us to be whole and balanced. While they start as inner movements in our nervous system, they show up as outer movements in the world: in how we communicate, organize our time, make decisions, handle conflict, lead teams, manage our lives, and run companies. Those who learn to recognize and skillfully use these patterns move themselves to greatness—that is, to their greatest capacity and sustaining renewal.

THE WAY TO BALANCE

Even if they don’t all mean the same thing by “balance,” virtually every leader I talk to hungers for more of it. When I teach people about the energy patterns, I often start by asking them to reflect on how balanced their lives are. I read off a list of 10 symptoms of imbalance—frenetic energy, difficulty sleeping, health problems, and so on—and have them mark which symptoms apply. “By show of hands, how many have 10 tick marks?” I ask at the end. A few hands go up. “Nine? Eight?” By “five” every hand in the room has been raised. Numerous studies confirm this growing sense of imbalance and the desire for greater balance. In a recent Fortune 500 survey, 84 percent of the executives said they would like a greater balance in their life and work, and nearly all (98 percent) are sympathetic to such requests from their employees.1

Most of these leaders feel caught up in the familiar bind of having to do more with less. They can’t keep up the way they used to, but the demands on them—especially if they’ve been successful and given more responsibility—continue to increase. “No matter how well you did last year, do more this year,” they’re told. As the pace gets faster, they find themselves juggling more meetings, more e-mail, more travel, more people to support, serve, or report to, more competing demands, more uncertainty, more, more, more. What driven people tend to do when work speeds up is to speed up with it, which keeps them stuck in the Driver pattern until they’re driving themselves and everyone around them toward exhaustion.

The Pitfalls of Balancing Time

When I ask people what they could do to bring better balance into their lives, they generally talk about leaving work at a certain time or keeping weekends free for family. In other words, they start with their calendar and ways of allocating their time. This approach doesn’t work too well for a couple of reasons. First, it’s hard to stick to, especially for people who are caught up in Drive and are ambitiously, urgently filling their lives trying to meet more demands. The way we run our day on the outside is characteristic of the patterns we most commonly use on the inside. Trying to find balance by making changes only to our schedule is, in a sense, working too far upstream.

I came across a great example of this in an article that contrasted the daily schedules of several CEOs.2 At one extreme was “The Overtime Guy,” Brett Yorkmark, CEO of the Nets basketball team. He’s up before 4:00 A.M., drives a fast car to work, races through e-mail, works out, makes deals (“Everything is a chance to drive revenue,” he tells his staff)—meets, greets, schmoozes all the way to and through a Nets game (victory!), driving himself through another 19-hour day.

Jim Buckmaster, the CEO of Craigslist.org, anchored the other end of the spectrum with his eight-hour-or-so workday spent mostly on the Web, a Blackberry beneath his thumbs and a keen intuition working away; his day is bracketed by chill time. Jim’s schedule would be inconceivable to a Driver like “Overtime” Brett. The pacing, appointments, surprises (are we even open to them?), and stresses of our day already contain so many conscious and less-than-conscious choices about Things That Matter. Trying to change our day on the outside without changing our internal patterns is deeply disquieting. People like Brett feel like they’re slacking when they cut back their hours, and without accessing counterbalancing patterns on the inside—the playful Collaborator or chill-time Visionary in Brett’s case—they don’t stick with it for long.

That’s not to say Jim has balance and Brett doesn’t, for balance is more subtle than hours in a workday, which is the second reason that a time-managed approach to balance doesn’t work very well: appropriating hours is not really the point. The point, rather, is to have the energy to perform at our best without burning out, to engage our lives fully, give of our gifts, and renew ourselves as we go. Balance is a matter of managing energy rather than time. We can allocate hours to our family, for example, but if we’re anxious about work and not really present, the time neither balances nor renews us—and our family picks up on our anxiety as well. Time is wasted or wisely spent depending on our energy. Energy is what matters and energy turns into things that matter. This is as true in our own life as in our impact on others; as Drucker reminds us, managing energy is our fundamental job as leaders.

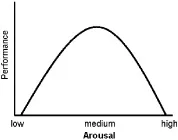

Energy Is Best Managed with a Pulse

Fortunately, a good deal is known about how to take charge of our energy and manage it well. More than 100 years of research tells us that, up to a point, energy rises to a challenge.3 Too little challenge or stress and we rust out: we never reach all that we’re capable of. But too much stress and we burn out. In between lies an optimal balance of our best sustainable performance. Moreover, this balance is not achieved by working our guts out for 50 weeks a year and then expecting a twoweek blowout vacation to renew us. That’s the absolute worst way to manage our energy, as it allows all the stress-induced hormones our body manufactures to wreak their internal havoc most of the time.

Rather, energy is best managed in bite-sized chunks. Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz, in their terrific book, The Power of Full Engagement, show that optimal, sustainable performance “requires cultivating a dynamic balance between expenditure of energy (stress) and renewal of energy (recovery).” It calls for alternating drive and recovery. Pushing and then renewing. Stretching to our limits and then resting. Finding this rhythm between pushing ourselves and then recovering is also the way we grow. As Loehr and Schwartz continue, “The key to expanding capacity is to both push beyond one’s ordinary limits and to regularly seek recovery, which is when growth actually occurs.”

So the real question of balance for Brett or Jim or you or me is not “How many hours do you work?” but “Are you performing at your best and can you keep up this pace?” Sustainable growth, peak performance, and ongoing renewal are possible only when we manage our energy with a pulse, only when we’re able to move in and out of drive. In the most physical, practical sense, this calls for moving between the Driver pattern (pushing) and the other patterns that allow recovery by quieting down (Organizer), playing (Collaborator), or letting go (Visionary). Stretching to our limits could also involve moving into a pattern that’s uncomfortable for us—which takes a good deal of energy—and then renewing ourselves by returning to our most comfortable, or Home, pattern.

As for Overtime Brett, maybe he’s doing just fine; maybe he’s finding small ways to recover during his day and his pace is a perfectly matched pulse of drive and renewal. But the breathless evidence would suggest otherwise; we might guess that Brett is in over-Drive and eventually will either learn balance or pay a price for the lack of it.

The stakes for balance are high; the alternatives are suboptimal performance, lack of growth, exhaustion, even illness and injury. The way to balance is to dynamically manage our energy. And the way to manage our energy is, fundamentally, at the source, using the four essential energies.

THE WAY TO WHOLENESS

The way to wholeness through the patterns is the process of discovering and reclaiming the depth and breadth of who we are. Depth is connecting what we do with who we are, making our actions on the outside an authentic expression of who we are on the inside. Breadth is the versatility to handle whatever life throws at us and still add our value.

Leading with Authentic Depth

Let’s consider depth first. Kevin Cashman, founder and president of LeaderSource, who studied what it takes for good athletes to reach greatness, came to two conclusions that apply more generally to moving to greatness. First, the athletes had to be in the right game. It had to be their game, a game for which they had abundant talent and passion. Second, they had to practice, practice, practice. The best basketball players were first to the court in the morning and the last to leave at night, practicing 2,500 jump shots a day, so strong was their passion and so high were their standards.

Being great in our own game—whether it’s sports or leadership—is only possible when outside matches inside, that is, when our actions are an authentic expression of who we are and what we’re feeling on the inside. We may be able to perform acceptably well when we’re motoring through on the surface, such as making social chitchat with our colleagues when we’d rather be analyzing sales figures. But if we want to become great at engaging people so deeply that we can get them moving with us, we have to feel it on the inside. A perfunctory surface act might get us to good, but only when our whole being s...