![]()

Part 1

About anxiety

![]()

1

What is anxiety and when is it an illness?

That’s easy. Anxiety is fear. It’s a normal, healthy emotion which nearly all of us experience (as I’ll explain later, sociopaths don’t get anxious). We need some anxiety, in the right place at the right time, in order to get ourselves going and to avoid too much danger. One of the reasons I kept somewhere near to schedule during my working life was because I was anxious to avoid my patients being cross with me for being kept waiting. Without anxiety, you would be unlikely to avoid that group of drunk football supporters milling around the railway station on a Saturday night. That would be a bad choice. A degree of anxiety helps us to make safe and well-judged decisions.

Anxiety is part of the ‘fight-or-flight reaction’. We have inherited this response to perceived danger from our forebears and they from theirs, stretching right back to the lower primates, through natural selection. It’s highly efficient, turning a resting animal into one that can run or fight to its maximum potential. That is achieved through the hormone adrenaline. This remarkable substance is released into the bloodstream automatically when the animal perceives threat. It worked really well when we lived on the primordial plain, making us pretty good at escaping from sabre-tooth tigers and the like. It causes an increase in heart rate, allowing more blood to be pumped around the body, targets blood to the muscles and internal organs where it is most needed in a crisis (you may notice that a person who is very anxious or shocked goes pale), causes sweating, allowing you to lose heat while running from or fighting with your pursuer, increases acuity of all the senses (things seem brighter, louder, sharper) and tends to encourage the bowels to empty from both ends (making you as light as possible enabling you to run as fast as you can, while also laying a confusing scent trail for the animal chasing you). Your muscles go into a state of tension, ready for a fight to the death, particularly the so-called ‘ballistic’ muscles in the arms, shoulders and legs, used for throwing, tearing, punching, kicking and running. Your shoulders tend to hunch up, making you the smallest possible target for a leaping animal or a thrown spear.

So anxiety works really well if you’re being chased by a sabre-tooth tiger or someone with a very sharp weapon. Other specific forms of anxiety were equally adaptive in the distant past. For example, a fear of snakes or spiders probably increased our ancestors’ chances of survival. Why is fear of snakes common, while fear of electricity is rare? The answer is that snakes and the danger some of them pose have been around for longer and so natural selection has had a chance to breed fear of them into us. Fear of open spaces is, probably for good reason, common among small mammals. For example mice, which are low in the food chain, will always cross a room hugging the walls and, if prevented from doing so, will exhibit panic. So agoraphobia is adaptive, at least for rodents. However, there aren’t that many situations or animals which threaten life and limb in most places where we live and work nowadays. Therein lies the problem. Our bodies are out of date, being designed for life as it was millions of years ago, not as it is now. Natural selection has stopped, as there aren’t many things in our modern world which are likely to kill you before child-bearing age, which is what natural selection works on. And, in any case, our bodies don’t know the difference between fear (anxiety) and anger (resentment). Either way, your body does the same thing, gets geared up for a fight to the death.

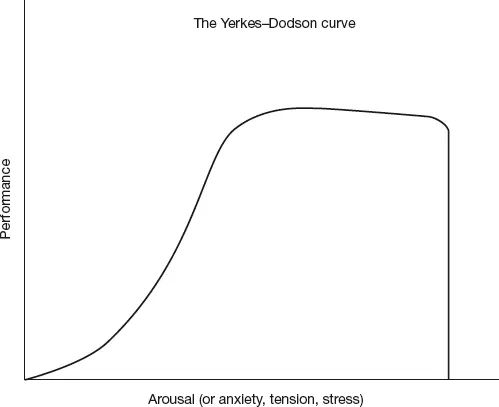

Anxiety is part of a continuum that extends from deep sleep, through relaxation, alertness, keyed-up, and on to terror and panic. The level at which you are able to function depends on your level of arousal. As you will see from Figure 1 (called the Yerkes–Dodson curve after the researchers who first drew it), there is a fairly broad plateau of arousal at which you’re able to function at your peak, but the fall-off when it happens is sudden and precipitous. It only takes a little more arousal to go from being on top of your game to dissembling in panic.

Figure 1 The Yerkes–Dodson curve

The problems occur when your arousal level or the degree of fear you experience is out of kilter with the situation you find yourself in. Or if you are fearful all of the time. Or if fear is automatically generated by specific harmless objects or situations. Or if the fear you suffer stops you from acting as you would or doing the things you would choose to do, were it at the level experienced by most other people. Or if your fear generates feelings, sensations or symptoms which cause you to suffer (and which increase your fear, leading to a vicious cycle). Or if you keep falling over the edge of the Yerkes–Dodson curve. Or if the real reason why you’re so wound up is that you’re angry and resentful.

If your fear is disabling, not just for a moment but repeatedly or constantly, you have an illness, an anxiety disorder. If you do, you’re not alone, though it may feel as if you are. In fact, anxiety disorders are very common. Nearly one in three women and one in five men will suffer from one or other of these conditions at some point in their lives. About one in ten suffer panic attacks, at least occasionally, and a similar number have specific phobias (such as animals, contamination etc.). One in seven suffer with social phobia (social anxiety disorder) and one in thirty suffer with agoraphobia. Between one in ten and one in twenty are disabled by constant anxiety (that is, fear without a specific focus). Up to one in twenty of the population are disabled by health anxiety and this rises to one in five people sitting in a GP waiting room. Anxiety disorders are common, especially in women, who are afflicted roughly twice as often as men. People who are separated, divorced, unemployed or a home-maker (housewife or househusband) are at greater risk of suffering from an anxiety disorder, as are those who for any reason are isolated from the social supports that sustain most of us.

There is a big overlap between anxiety disorders and depressive illness (major depression). Most people suffering with a depressive illness are also plagued by anxiety. While the majority of those suffering with anxiety disorders don’t have a depressive illness, most are prone to low mood, sometimes severely so. If the worst aspect of your suffering is deep, black depression, I would suggest you read one of my other books, Depressive Illness: The curse of the strong and, please, go to see your GP.

Anxiety comes in lots of different shapes and sizes. I’ve mentioned most of the different types of anxiety disorders already, but it’s worth describing them in a bit more detail. Just one aside: I’m not going to deal with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in this book. While it is a condition driven by anxiety, it is a very big subject and deserves its own book. The same is true for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Fortunately, there are several excellent books available to help people who suffer from those conditions.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a state of constant fearfulness, a sense that disaster is waiting around the corner, ready to pounce once your back is turned. This is often at the core of the condition; a feeling that you have to be constantly alert to danger, lest it catch you unawares. You are constantly worrying, however hard you try not to. You vigilantly scan your environment, searching for signs that something is wrong. Your muscles are always tense and, because they are ballistic not postural muscles, they aren’t designed to be in tension for long periods and so tend to cramp up. Your pulse rate, breathing and blood pressure tend to be on the high side and you tend towards loose bowels and a ‘churning stomach’. In other words, you are more or less constantly under the effects of adrenaline. You tend to have difficulty sleeping, you can’t relax and you are often jumpy and irritable. That is, your brain is in a state of constant overarousal, running too hot all the time.

Someone suffering from panic disorder (PD) on the other hand tends to be less anxious for much of the time. Either out of the blue, or triggered by specific circumstances, a full-blown fight-or-flight reaction occurs (a panic attack) with breathlessness, racing heartbeat, sweating, nausea, an urge to escape and sometimes a feeling that you are going to faint or even die (you won’t). If the panic attacks are linked to social phobia, you may experience blushing. While some people have both generalized anxiety and panic attacks, some really aren’t exceptionally anxious between attacks. You may even wake up at night with a panic attack.

Phobic anxiety disorder (PAD) is a catch-all label, referring to anxiety generated by specific objects (such as certain animals) or situations (such as being trapped in enclosed spaces). Fear grows as you anticipate the situation, producing the symptoms of anxiety which I have outlined, leading to avoidance and, over time, to an increase in the fear you experience, which can only be allayed by further avoidance. And so it goes on.

I find it useful to separate out two types of phobia, as they have a lot of aspects that are different from the types of PAD I have described, and they are agoraphobia and social anxiety disorder (SAD).

Agoraphobia (AP) is literally a fear of open spaces. In practice, it usually means you become increasingly fearful the further you are from home or the environment where you feel safe and secure. As you leave your safe place, you suffer increasingly severe anxiety and the physical symptoms which go with it. You may suffer panic attacks and the fear of fear spiral causes you to be as fearful of the attacks as of the situation itself. As you will gather, there is a big overlap between agoraphobia and PD. You fear that you will lose control, causing you to embarrass yourself in public, or that you will faint, die or go mad (you won’t).

Social anxiety disorder (also called social phobia (SP)) is an often quite disabling condition resulting from an excessive sensitivity to the opinions of others, in turn usually caused by low self-esteem and shyness. In social situations you feel inadequate and exposed and you are overwhelmed by a fear of embarrassing yourself. Commonly, you fear blushing and you imagine that everyone will see your face flush and judge you for it. The anxiety this causes may lead to some blushing, confirming your fears. You may fear losing control of your bowels and again this fear may lead to some urgency in needing the toilet, or you may fear your body shaking, leading to a tremor in your hands. SP may be restricted to situations in which you have to perform, such as public speaking, or may involve any situation in which you have to interact with people.

Health anxiety disorder (HAD) refers to a condition in which you are constantly preoccupied by a fear of serious (or fatal) illness. You may or may not have a diagnosed physical illness, but the point is that the severity of your anxiety and the degree of suffering which your symptoms cause you is out of proportion to the underlying physical pathology in your body. There’s the problem. How do you know that there isn’t something major and potentially fatal lying behind the symptoms you are experiencing? Maybe your doctor just hasn’t found it yet. The truth is that you can never be 100 per cent certain about anything, but most doctors accept that there is a limit to how many investigations should be carried out when each one before has failed to find something that needs treatment. If you suffer with HAD you can’t stop looking for a cause of your discomfort, being sure that something catastrophic underlies it. You spend every minute of every day ruminating anxiously about your fears and, as we’ve discussed, that anxiety causes more symptoms. When I explain this, you answer angrily: ‘So you’re saying it’s all in my head are you?’ No, I’m not. Your symptoms and the suffering they cause you are real. The only questions are what causes them and how can they best be treated? This is, in my view, the most difficult type of anxiety disorder to treat. The dividing line between your doctor listening to and respecting your concerns and following up on them on the one hand, and making things worse by over-investigation on the other is blurred. I think I have an answer to this conundrum, but more on that later.

So who gets these conditions? I’m going to deal with what causes them and how they develop in the next chapter, but for now I will just observe that most of those who came to see me suffering with anxiety disorders were people who had a very low opinion of themselves (and the world and the future). They were ashamed of themselves. Now, there are people in the world who really should be ashamed of themselves (think Palace of Westminster, The White House, Kremlin), but not these folks, who try so hard. Those who should be aren’t, but those who shouldn’t be are. Hmm, maybe there’s a key there …

From here on, I will use the following abbreviations for brevity:

| Generalized anxiety disorder – GAD | Phobic anxiety disorder – PAD |

| Panic disorder – PD | Agoraphobia – AP |

| Social anxiety disorder – SAD | Health anxiety disorder – HAD |

![]()

2

What causes anxiety disorders?

When, in the 1950s, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was asked by a journalist what in political life he most feared, he replied: ‘Events, dear boy, events.’ So the story goes. Or as Americans like to say: ‘S—t happens.’ So is that it? Is it the stuff which happens to us which makes us anxious? Do people believe that life is going to keep going wrong the way it has up until now? Are the most anxious people those who have endured the most adversity? Well, to an extent, but there’s a lot more to it than that. It looks as though the loss of hope that things will get better has more to do with depression than anxiety. If depression is despairing of anything improving, of mourning what has been lost, then anxiety is fear that things will get worse, that what you have will be taken away. As such, it has always seemed to me that in seeking to deal with disabling anxiety we need to look at our relationship with the future more than the past.

Genes

But to do that we have to understand where anxiety comes from, so let’s start at the beginning, with our genes. It does look as though our tendency to anxiety is, to a large extent, passed down from our parents. A part of that effect is genetic; this has been established by studies looking at the chances of a non-identical twin suffering with anxiety if their twin has an anxiety disorder, and comparing these with identical twins where one has the condition. This separates out the effect of genes (the same in identical twins but different in non-identical twins) and environmental/learning factors (the same in both). Unfortunately, the research isn’t completely clear on this question, but it looks like what you learn in childhood is more important than the genes you carry, at least for most types of anxiety disorder. With GAD, there may be a bigger genetic influence, but this may be because of the common ground between GAD and depressive illness (depression has a strong genetic component), which I mentioned in Chapter 1.

In summary, blaming your anxiety on your genes doesn’t work.

Brain physiology and chemistry

Biological psychiatrists have been trying to explain anxiety disorders in terms of abnormal functioning of one or another brain part or system for years without, as yet, consistent success. The number of theories abound and, frankly, it makes my head spin, but a few things are clear and worth understanding.

Fear seems to be generated mainly in a structure deep within the brain called the amygdala. This structure is programmed to discharge impulses to other parts of the brain in response to perceived threat, or even lack of evidence of safety. The effect is to switch these structures on, in particular those in the brain stem and another structure, the hypothalamus, which together control the fight-or-flight reaction and the body’s longer-term responses to stress. The amygdala is a primitive structure, which we have in common with all primates, and it acts automatically, unless it is prevented from doing so. The only su...