1

What is astronomy?

‘Everybody knows what astronomy is all about.’ Unfortunately, this statement is not true. Even today many people confuse astronomy with astrology, and expect me to be able to peer into the future, probably by using a crystal ball. Yet the two subjects could not possibly be more different. Astronomy is the science of the sky and all the objects in it, from the Sun and Moon through to the remote star systems that are so far away that we see them as they used to be thousands of millions of years ago. Astrology, which attempts to link the stars with human character and destiny, is a relic of the past; it is totally without foundation, and the best that can be said of it is that it is fairly harmless.

In this chapter you will learn some basic facts about astronomy and the definitions of the most important terms.

Suns, stars and planets

It may be helpful to begin with a celestial roll-call. Obviously we must start with our Earth, which was once thought to be the most important body in the entire universe, but which we now know to be an insignificant planet moving around an insignificant star – the Sun. The distance between the Sun and the Earth is 149.5 million km (93 million miles), and it takes one year for the Earth to complete a full circuit: more precisely, 365.2 days. The Earth spins around once in approximately 24 hours, and is surrounded by a layer of atmosphere that extends upwards for several hundreds of miles even though most of it is concentrated at low levels.

At 149.5 million km (93 million miles) from us, the Sun seems a long way away, but in astronomy we have to deal with immense distances and vast spans of time. Nobody can really understand figures of this sort – certainly I have no proper appreciation of even 1 million km (0.6 million miles) – but we know that the values are correct, and we simply have to accept them.

Just as the Earth is an ordinary planet, so the Sun is an ordinary star. All the stars you can see on any clear night are themselves suns, some of them far larger, hotter and more luminous than ours. They appear so much smaller and dimmer only because they are so much further away. Represent the Earth–Sun distance by 2.5 cm (1 inch), and the nearest star will be over 6.5 km (4 miles) away. The Pole Star, which many people recognize (and about which I will have more to say in the next chapter) will have to be taken to a distance of 11,260 km (7,000 miles). It is at least 6,000 times more luminous than the Sun, and yet it seems by no means the most brilliant star in the night sky.

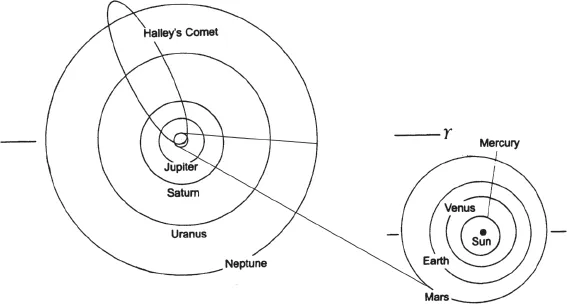

Figure 1.1 Plan of the Solar System, including Halley’s Comet

Around the Sun move eight planets, of which the Earth comes third in order of distance. Mercury and Venus are closer to the Sun than we are; Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are further away.

Unlike the stars, planets have no light of their own, but shine only because they reflect the rays of the Sun. If some malevolent demon suddenly snatched the Sun out of the sky, the planets (and the Moon) would vanish from sight, though naturally the other stars would be unaffected.

The planets move around the Sun at different distances and in different periods. Even a casual glance at a plan of the Sun’s family, or Solar System, shows that it is divided into two well-marked parts (see Figure 1.1). First we have the four small planets (Mercury to Mars) and then a wide gap, followed by the four giants (Jupiter to Neptune). The wide gap between the paths or orbits of Mars and Jupiter is occupied by a swarm of very small worlds known variously as minor planets, planetoids and (more commonly) asteroids.

The revolution periods of the planets range from 88 days for Mercury to almost 165 years for Neptune. They are very different sizes: Jupiter is over 143,000 km (89,000 miles) in diameter, Mercury only just over 4,800 km (3,000 miles). Because the planets are relatively near neighbours, some of them can look most imposing. Venus, Jupiter and Mars at their best are far brighter than any of the stars, while Saturn is prominent enough to be conspicuous, and Mercury can often be seen in the twilight or dawn sky. All these planets have been known since very ancient times, while the others were discovered much more recently: Uranus in 1781 and Neptune in 1846. Uranus can just be seen with the naked eye if you know where to look for it, but to observe Neptune you need optical aid.

Satellites, comets and meteorites

What, then, of the Moon, which dominates the night sky just as the Sun is king of day? Officially the Moon is known as the Earth’s satellite; it moves around us at a distance of less than 402,250 km (250,000 miles), and it is little more than 3,200 km (2,000 miles) across. Like the planets, it depends upon reflected sunlight. Obviously the Sun can illuminate only half of the Moon at any one time, and this is why we see the regular phases, or apparent changes of shape, from new to full; everything depends upon how much of the Moon’s sunlit hemisphere is turned in our direction. It is an airless, waterless, lifeless world, but it is our faithful companion in space, and stays together with us in our never-ending journey around the Sun. It takes just over 27 days to complete one orbit of the Earth although, for reasons to be explained later, the interval between one new moon and the next is 29.5 days.

Other planets have satellites of their own – more than 60 each for Jupiter and Saturn – but in some ways the Earth–Moon system is unique, and it may be better to regard it as a double planet rather than as a planet and a satellite.

Among other members of the Sun’s family are comets, which have been referred to as ‘dirty snowballs’. They are flimsy, wraithlike things; with even a major comet the only substantial part is the nucleus, made up of a mixture of ice and ‘rubble’ and seldom more than a few kilometres across. Like the planets, comets travel around the Sun but, whereas the orbits of the planets are almost circular, those of the comets are, in most cases, very eccentric. When a comet nears the Sun, its ices begin to evaporate, and the comet may produce a gaseous head and a long tail; when the comet retreats once more into the cold depths of the Solar System, the head and tail disappear, leaving only the inert nucleus. The only bright comet to appear regularly is Halley’s (named in honour of the second Astronomer Royal, Edmond Halley), which comes back every 76 years and last paid a visit to the Sun in 1986. Really brilliant comets have much longer periods, so that we cannot predict them. Now and then a comet meets with a dramatic end, as in July 1994 when a comet known as Shoemaker–Levy 9 crashed to destruction upon the planet Jupiter.

Note that a comet moves well above the top of the Earth’s air and is a long way away, so that it does not seem to crawl quickly across the sky; if you see a shining object that is shifting perceptibly, it cannot be a comet.

As a comet travels, it leaves a trail of ‘dust’ behind it. If one of these dusty particles dashes into the upper atmosphere, it will have to push its way through the air particles, so that it becomes heated by friction and burns away in the streak of luminosity that we call a meteor or shooting star. Therefore, a shooting star has absolutely no connection with a real star; it is a tiny piece of débris, usually much smaller than a pin’s head, which we see only during the last few seconds of its life before it burns away completely, ending its journey to the ground in the form of ultra-fine dust.

Larger bodies, not associated with comets, may survive the full drop without being burned away, and are then known as meteorites. Some of them may make craters; for example, the Arizona Crater in the United States was certainly formed by an impact more than 50,000 years ago. Meteorites come from the asteroid belt, and in fact there is no difference between a large meteorite and a small asteroid; it is all a question of terminology. In recent years, several tiny asteroids, much less than 1.6 km (1 mile) across, have been known to pass by us at less than half the distance of the Moon. One of these cosmical midgets is believed to have been no more than 9 m (30 ft) in diameter.

The planets move around the Sun in very much the same plane, so that, if we draw a plan of the Solar System on a flat piece of paper, it is not far wrong. This does not apply to the comets or asteroids, and indeed some comets move around the Sun in a ‘wrong-way’ or retrograde direction; Halley’s Comet is one of these. In addition, there is a great deal of material spread thinly along the main plane of the system, which shows up when lit by the Sun and produces the lovely cone-shaped glow that we call the Zodiacal Light.

Constellation patterns

The planets were first identified because, unlike the stars, they shift in position from one night to another; indeed, the word ‘planet’ really means ‘wanderer’. The stars are so remote that the individual or proper motions are very slight, and the star-patterns or constellations seem to remain to all intents and purposes unchanged over periods of many lifetimes. Board Dr Who’s time machine and project yourself back to the age of William the Conqueror, or Julius Caesar, or even Homer: the constellation patterns will appear practically the same as they do now. It is only the members of the Solar System which move more obviously against the background, and even then the Sun, Moon and principal planets keep strictly to a band around the sky which we call the Zodiac.

The constellations that we use today have come down to us from the Greeks. The last great astronomer of classical times, Ptolemy, gave a list of 48 constellations, all of which are still to be found on our maps even though their boundaries have been modified and new groups added. The Greek names (suitably Latinized) commemorate the mythological gods and heroes, together with living creatures and a few inanimate objects. Thus we have Orion (the Hunter), Hercules (the legendary hero), Ursa Major (the Great Bear), Taurus (the Bull) and others. Probably the best-known constellations visible from northern countries are the Great Bear and Orion, both of which are distinctive; the Bear never sets over Britain, though Orion is out of view during the summer because the Sun is too close to it in the sky. Yet it is important to remember that ...