![]()

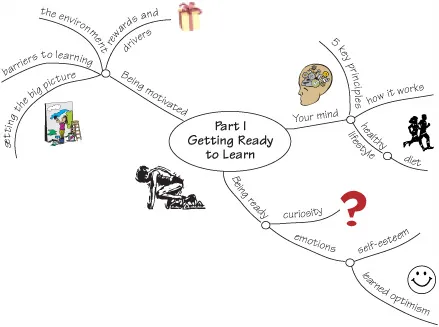

Part I

Get Ready to Learn

Going beneath the surface

COMING UP IN THIS PART

A guided tour of your brain

How to look after your brain

How to be emotionally ready to learn

How to motivate yourself to learn

How to create a good learning environment

How to overcome barriers to learning

PART I LOOKS LIKE THIS

A KEY SENTENCE TO REMEMBER FROM THIS SECTION

When it comes to our mind, most of us know less about it than we do about the engine of our car.

A FAMOUS THOUGHT TO CONSIDER

Life is like a ten speed bicycle: most of us have gears we never use.

Charles M Schulz

![]()

1

Unpacking Your Mind

No one would think of lighting a fire today by rubbing two sticks together. Yet much of what passes for education is based on equally outdated concepts.

Gordon Dryden, The Learning Revolution

WE ALL GO TO SCHOOL, WHERE WE LEARN SUBJECTS LIKE SCIENCE AND history. We also develop various skills, mostly related to subjects but also some life skills. Strangely, however, very few people I meet have ever been taught how to learn. We talk about literacy and numeracy—but what about “learnacy”?

When I talk to audiences I ask them which they think is the most important part of their body when it comes to learning. Not surprisingly, they point to their heads. I then ask them how much time they spent at school or college or business school learning about their minds and there is an embarrassed and, increasingly these days, a worried silence. People are beginning to understand the real importance of the concept of learnacy, first talked about by Guy Claxton a few years ago.

The situation is similar across organizations of all kinds. There is much talk of global marketplaces, performance, cost cutting, knowledge management, culture, values, leadership development, and so on. But in most cases, how you might use your mind to learn to perform more effectively is simply not on the agenda.

It is as if there is a conspiracy of silence when it comes to learning to learn. We invest huge sums of money in business processes, in research and development, in computer systems, and in management training, but almost nothing in understanding how the minds of our employees and colleagues work—or, indeed, how our own mind functions.

Nevertheless, talk to most managers today and it is the quality of their people that is apparently critical to their success. The old ingredients like price and product are taking second place to the way your people deal with your customers. This unique resource—people’s ability to learn—is arguably the only source of competitive advantage naturally available to all organizations, and it is so often ignored.

There can be little doubt that how we learn is central to success in today’s fast-changing world. As the great educator John Holt put it in the 1960s:

Since we cannot know what knowledge will be most needed in the future, it is senseless to try and teach it in advance. Instead we should try to turn out people who love learning so much and learn so well that they will be able to learn whatever needs to be learned.

This is as true today as it was 40 years ago. But our understanding of how our brains work has advanced along with the extraordinary speed of technical change, so that common sense and science may well have caught up with each other at last.

By reading this book and taking time to reflect on the knowledge that is lying hidden beneath the surface of your life, you will be able to power up your own mind and the minds of those with whom you work and live.

TAKING YOUR MIND OUT OF ITS BOX

Imagine you have just bought a computer or some electrical item for the home. You are unpacking it for the first time. As you undo the brown cardboard box, you are faced with various bits and pieces, some wrapped in plastic, some further packed in polystyrene. You recognize some things, while others perplex you. For a few brief moments you have a glimpse of the workings of some mechanical object before it has become a familiar part of your life. At the bottom of the box is a manual telling you how to put the bits together, how to get started, and how to get the best out of the product you have bought.

Most people have this kind of experience several times a year. We find out the basics of how an item of equipment works. With a more complex item, say a camera, we may go on to learn new techniques to ensure that we can use it effectively. We may acquire various guides to help us to take better pictures. Most of us who drive a car occasionally have to read its manual before trying to fix an indicator light that is not working. From time to time, we may even peer at the engine, seeking to coax it into life, although we may know very little about how the car works. Certainly, we need to fill the car up with fuel and water on a regular basis.

Yet, when it comes to our mind most of us know less about it than we know about the engine of our car. Our mind is so much a part of us, from our first memories onward, that we never stop to admire it or wonder how it works.

This book is going to help you “unpack” your mind, so that you can “reassemble” the component elements. Then, as with a camera, you can begin to use this “manual” to help you find out what your mind needs to work more effectively, to power it up.

Imagine you are “unpacking” your mind for the first time. Let’s start with your brain—although this is not all there is to your mind, as we will see later.

Imagine that you could take off the hard outside covering of the skull and look at what you have. It is a grey, slimy, slightly wobbly mass of human tissue. If you were able to bring yourself to hold it in your hands, it would weigh a little more than a typical bag of sugar.

Without doubt, you would be looking at the most complex piece of machinery in the world. It has been compared to a hydraulic system, a loom, a telephone exchange, a theater, a sponge, a city, and, not surprisingly, a computer. But it is more complicated than any of these. And, although we are still comparatively ignorant, we have begun to find out a little more about how it works in the last few decades.

In the next few pages you will find out some of the basic science underpinning the operation of your mind.

However, let me start with a health warning. As with all simple explanations of deeply complex issues, there is a danger that too much can be read into a few short paragraphs. Inevitably, this leads to disappointment. On the other hand, if you see what follows as a number of different ways of looking at your mysterious mind, possibly as metaphors, then you may find that more helpful. The neuroscientist Professor Susan Greenfield put it like this at a Royal Institution seminar:

It does not matter that popular science may not get things completely right; at least it offers a mental model for what is going on inside the brain.

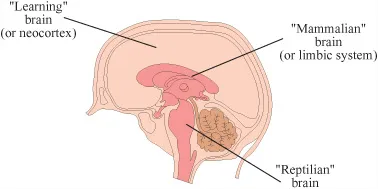

YOUR THREE BRAINS

In 1978 Paul Maclean proposed the idea that we have three brains, not one. This is a difficult notion to grasp, but stay with it for a moment. Imagine you can reach forward and remove the two outer brains: they will come away quite easily and you will be left with an apricot-sized object (see Figure 1). This is sometimes called your primitive or reptilian brain; as its name suggests, it is the bit that even simple creatures like reptiles have. It governs your most basic survival instincts, for example whether, if threatened, you will stay to fight or run away. It seems also to control other basic functions such as the circulation of your blood, your breathing, and your digestion.

Figure 1 Three brains

Now retrieve the smaller of the two “brains” that you took off earlier. It is shaped a bit like a collar and fits around the reptilian brain. It is sometimes referred to as your limbic system, after the Latin word limbus meaning border. This is the part of your brain that you share with most mammals. Scientists think it deals with some of the important functions driving mammals, for example, processing emotions, dealing with the input of the senses and with long-term memories.

Finally, pick up the outer, third brain. This is the part that sits behind your forehead and wraps around the whole of your mammalian brain. (Think of one of your hands held horizontally and palm downward, gripping your other hand that you have clenched into a fist.) You probably recognize this bit! It is the stuff of science fiction movies to see its crinkled and lined shape swimming in a glass jar of liquid. It is the most advanced of your three brains, your learning brain. It deals with most of the higher-order thinking and functions.

In evolutionary terms, your small, reptilian brain is the oldest and the outer, learning brain is the most recently acquired. Thinking about the brain in this way helps us see how human beings have progressed from primitive life forms. It also helps to explain in a very simple way why we cannot learn when we are under severe stress. In such situations it is as if a magic lever is pulled telling our outer learning brain to turn off and retreat, for survival’s sake, to our primitive brain. Here the choice is quite simple, flight or fight. It leaves no room for subtlety of higher thinking. At various stages throughout this book you will be able to find out how to avoid creating just such an unhelpful response.

Scientists are increasingly sure, however, that Maclean’s theories, sometimes known as the idea of the triune brain, are an oversimplification of the way the brain works. In fact, it is much more “plastic” and fluid in how it deals with different functions. Many parts of the brain can learn to perform new functions and there is much unused capacity.

YOUR DIVIDED BRAIN

Put the three parts of your brain back together and pause to admire them! Imagine you are a magician doing a trick with an orange, which you have secretly cut in half beforehand. You tap the orange and it magically falls neatly into two halves, a right and a left hemisphere, before an astonished audience. Imagine your brain falling into two halves, with the same startling effect.

The ancient Egyptians first noticed that the left side of our brain appeared to control the right half of our body, and vice versa. More recently and more significantly, in the 1960s Roger Sperry discovered that the two halves of the brain are associated with very different activities. It was he who first cut through the connection between them, known as the corpus callosum.

For many centuries before this, scientists thought that we had two brains, just as we have two kidneys, two ears, and two eyes. Work on stroke patients, however, where parts of their brains have been damaged, gives us some interesting further clues. It seems that the left side mainly handles sequential, mathematical, and logical issues, while the right is more creative and associative in the way it works. The left is literal, while the right enjoys metaphorical interpretation. The two sides perform different functions, the left side, for example, dealing with much of the brain’s language work.

Roger Ornstein, in The Right Mind, has since gone further in showing how the two halves actually work together and how the right side has a special role in dealing with the more complex overall meaning of many of the issues we face today.

Indeed, the idea of being left- or right-brained is becoming more commonly used in business. Ned Hermann, while working at General Electric, translated much of this into useful insights for the workplace, exploring how each of us has inbuilt preferences toward the left or the right side of our brains. The ...