![]()

PART 1

Man and machines: past, present, and future

![]()

1

The ascent of man

“Productivity growth isn’t everything; but in the long run it’s almost everything.”

Paul Krugman1

“The past 250 years could turn out to be a unique episode in human history.”

Robert Gordon2

If there is one event in our economic history that should be counted as a “singularity” it is surely the Industrial Revolution. Like all things historical that one learned about at school, the Industrial Revolution is more complicated than how it was presented back then. For a start, you could quite reasonably say that it wasn’t a revolution. After all, it wasn’t a single event but rather a process, starting in Great Britain in the late eighteenth century and drawn out over many decades.

And you could also say that it wasn’t exclusively, or perhaps even primarily, industrial. There were certainly great advances in manufacturing, but there were also great advances in agriculture, commerce, and finance. Moreover, what made the Industrial Revolution possible – and what made it happen in Britain – was less to do with material factors, such as the availability of coal and water power that we had drilled into us at school, and more to do with the political and institutional changes that had happened over the previous century.

But no matter. Whatever name you want to give it, it was momentous. Before the Industrial Revolution there was next to no economic progress. After it, there was nothing but.

This is a simplification, of course. There was some growth in per capita output and incomes beforehand, including in both the USA and Britain in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries – although the pace of advance was minimal compared to what came later.

Nor is it quite right to see economic progress as continuing relentlessly after the Industrial Revolution. As I will show in a moment, there have been some notable interruptions. Moreover, it took decades for there to be any increase in real living standards for ordinary people. 3

These various quibbles and qualifications have led some economic historians to question whether we should dispense altogether with the idea of the “Industrial Revolution.” Yet this would surely take revisionism too far. Rather like those historians who claim that, in contrast to their fearsome reputation, the Vikings were really nice, civilized, decent people, if not actually cuddly, in seeking to correct the simplicities of an established view, they have veered off too much in the other direction. The Vikings really were pretty scary, and the Industrial Revolution really was momentous.

One of the key characteristics of the post-Industrial Revolution world that marks it out as different from everything that came before is that, starting during the Victorian age in England, it came to be widely believed that the human condition would continue to get better and better, inevitably and inexorably. As the historian Ian Morris has put it, the Industrial Revolution “made mockery of all the drama of the world’s earlier history.”4

From ancient to modern times

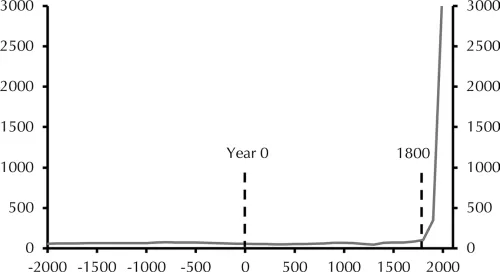

This message about the significance of the Industrial Revolution is borne out by Figure 1. It shows what has happened to per capita GDP from 2000 BCE to the present. Believe it or not! Clearly, the early data shown in the chart are pretty dodgy. They should be regarded as indicative at best. In fact, more than that. You can ignore the absolute numbers marked on the chart’s axes. They have no meaning. It is the relativities that should command attention. Per capita GDP in each year is compared with how it was in the year 1800. (In other words, all figures are indexed, with the year 1800 set equal to 100.)

FIGURE 1 World GDP per capita from 2000 BCE to the present day (the year 1800 = 100)

Source: DELONG, Capital Economics

As the chart shows, there was effectively no change in per capita GDP from 2000 BCE to the birth of Christ, marked on the chart as Year 0. From then to 1800 per capita GDP doubled. This may not sound that bad but bear in mind that it took us 1,800 years to achieve this result! In regard to the rate of increase from one year to the next, it amounts to next to nothing. (That is why you can hardly make out any rise on the chart.) Moreover, the improvement was heavily concentrated in the later years.5

But after the Industrial Revolution things were utterly different. The chart clearly shows the lift-off. In 1900 per capita GDP was almost three and a half times the 1800 level. And in 2000 it was over thirty times the 1800 level.6 The Industrial Revolution really was revolutionary. It provides the essential yardstick against which we must measure and assess the advent of robots and AI.7

In what follows, I trace out and discuss the major features of our economic history from ancient times, through the Industrial Revolution to the present. But I hope that readers will understand that, compared to my more detailed discussion of recent decades, coverage of earlier centuries is thinner and I breeze through time much more quickly. This is both because we have much less information about our distant history and because, as we contemplate the potential economic effects of robots and AI, ancient times are of less interest and relevance than recent decades.

Ancient puzzles

Right at the heart of the Industrial Revolution was technological change.8 Yet there were some notable milestones in technological development well before the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, going a fair way back into history there were dramatic advances such as the domestication of animals, the plantation of crops, and the invention of the wheel. But they don’t show up clearly in our record of world GDP per head. Believe it or not, this “record,” or rather the economist Brad DeLong’s heroic efforts to construct one, goes back to one million years BCE. (There is no point in extending Figure 1 this far back because all you would see is a practically flat line, and this would obscure the significance of what happened over the last 200 years.)

Now, admittedly, the absence of much recorded economic growth in earlier periods could simply be because our economic statistics are hopelessly inadequate. They certainly are poor and patchy. But we don’t have only this inadequate data to go on. The evidence from art, archaeology, and such written accounts as we have, all point to the conclusion that the economic fundamentals of life did not change much across the centuries, at least once mankind abandoned nomadism for a settled life.

Why did these earlier, apparently revolutionary technological developments, referred to above, not bring an economic leap forward? The answer may shine a light on some of the key issues about economic growth that haunt us today, and in the process pose important questions about the robot and AI revolution.

I am sorry to say, though, that there isn’t one clear and settled answer to this important historical question. Rather, four possible explanations suggest themselves. I am going to give you all four without coming to a verdict as to which explanation is the most cogent. We can leave that to the economic historians to scrap over. In any case, the truth may well be a mixture of all four. What’s more, each of these possible explanations has resonance for the subject of this enquiry, namely the economic impact of robots and AI.

The first seems prosaic, but it is nonetheless important. Momentous developments such as the First Agricultural Revolution, involving the domestication of animals and the plantation of crops, which can be said to have begun about 10,000 BCE, were stretched out over a very long time. Accordingly, even if the cumulative effect once the process was complete was indeed momentous, the changes to average output and living standards did not amount to much on a year-by-year basis.9

The second possible explanation is structural and distributional. For a technological improvement in one sector (e.g., agriculture) to result in much increased productivity for the economy overall, the labor released in the rapidly improving sector has to be capable of being employed productively in other parts of the economy. But as the First Agricultural Revolution took hold, there were effectively no other forms of productive employment. Hence the proliferation of temple attendants, pyramid builders, and domestic servants. The anthropologist James Scott has suggested that after the First Agricultural Revolution average living standards for the mass of the population actually declined.10 Nor was there anything in the new agrarian economy, with its lopsided income and wealth distribution, that favored further technological developments.

From technology to prosperity

The third possible explanation is that technological advance alone is not enough to deliver economic progress. You have to have the resources available to devote to new methods and to make the tools or equipment in which technological progress is usually embodied. Accordingly, growth requires the forgoing of current consumption in order to devote resources to provision for the future. Human nature being what it is, and the demands for immediate gratification being so pressing, this is easier said than done.

Unfortunately, the sketchiness of our data on the distant past again precludes us from conclusively establishing the truth on this matter. But it seems likely that ancient societies were unable to generate much of a surplus of income over consumption that could be devoted to the accumulation of capital. And we also have to take account of the destruction of capital in the various wars and conflicts to which the ancient world was prone. So the net accumulation of capital was probably nugatory.

Such surpluses as were generated from ordinary activities seem to have gone predominantly into supporting the existence of nonproductive parts of society, such as a priestly caste, or the construction of tombs and monuments. In ancient Egypt, heaven knows what proportion of GDP was devoted to the construction of the pyramids or, in medieval Europe, to the erection of the splendid, and splendidly extravagant, cathedrals that soared above the seas of poverty all around. It is wonderful that these remarkable buildings are there for us to enjoy today. But they didn’t exactly do much for the living standards of the people who were awed by them when they were built – nor for the rate of technological progress, either then or subsequently.

The demographic factor

The fourth reason that technological progress did not automatically lead to increased living standards is that the population rose to soak up whatever advantages were gained in production. The evidence suggests that for the world as a whole there was annual average growth of about 0.3 percent in the sixteenth century, but population growth averaged 0.2 percent per annum, leaving the growth in GDP per capita at a mere 0.1 percent, or next to nothing. Similarly, in the eighteenth century, just before the Industrial Revolution, global growth appears to have averaged about 0.5 percent, but again just about all of this was matched by an increase in population, meaning that the growth in real GDP per head was negligible.11

Admittedly, the linkages here are not straightforward. After all, an increased number of people was not an unmitigated disaster, imposing a burden on society, as is so often, erroneously, assumed. On the contrary. More people meant more workers, and that would tend to increase overall production. But applying more workers to a given amount of capital and land would tend to produce lower average output. (Economists know this as the law of diminishing returns.) Moreover, a higher rate of population growth would mean a higher ratio of nonproductive children to productive adults. (Mind you, just as in many poor societies today, stringent efforts were made to make children to some degree productive from an early age.)

The constraints on living standards imposed by rising population were the central element in the theory propounded by the Reverend Thomas Malthus, who was both a minister of the Church and one of the early economists. These days his rank pessimism has been completely discredited. And rightly so. He really did give economics and economists a bad name. Writing in England in 1798, he said:

The power of population is so superior to the power of the earth to produce subsistence for man, that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction; and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and ten thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the world.12

In one of the rare forays of an economist into the realms of carnal desire, he warned that the “passion between the sexes,” if left unregulated, would result in misery and vice. He urged that the “consequences of our natural passions” be frequently brought to “the test of utility.”13

Here lies a lesson for all those authors, both techie and economic, who currently wax lyrical on the horrors that human beings face in the robot-dominated future. You are entitled to be that gloomy if you like, but if you are, and wish to preserve your reputation, you had better be right.

Poor old Malthus. If ever an economist got things comprehensively wrong, it was him. Over the last 200 years – although not quite as soon as the ink was dry on his writings – per capita GDP and living standards have shown a dramatic rise. From 1798, the year Malthus published his gloomy tome, to today, the cumulative increase in real per capita GDP in the UK has been over 1,300 percent. And the increase in living standards (on which we don’t have full data) would not be much differe...