![]()

PARTICIPATION

Have you ever heard of a hassle graph?

Maybe not. But you’ve probably been on a team that tried to move fast by skipping all the “getting to know you” stuff, only to stumble and struggle later on. Andre Alphonso, former managing director of Forum Australia and founder and CEO of Forum India, recalls:

In Influence programs I would draw a graph: on the vertical axis was hassle, on the horizontal axis was time. Typically a project starts off very low on hassle, and hassle increases over time. When you really want stuff to be working, later in the project, that’s when hassle gets high. You need to move some of the hassle up front, with discussion of roles and ground rules. You need to front-load the hassle so it goes down over time, instead of up. I called it the Hassle Graph.*

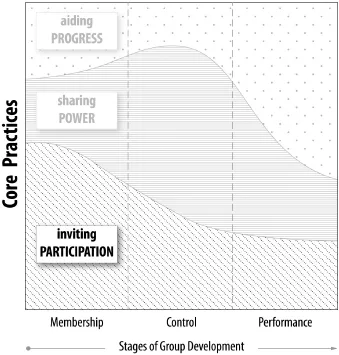

In Membership, the first stage of any group endeavor, we can begin to smooth out the hassle graph by inviting participation (see Figure I.1). Leadership development expert Maggie Walsh, who for several years headed Forum’s leadership practice, echoes Andre when she says inviting participation is about “front-loading buy-in.” The more time and effort we invest early on to create a real group—that is, one whose members feel welcomed and integral rather than overlooked and dispensable—the more time and effort we save later, when problems inevitably crop up and unity is tested. This is true whether the group consists of two people or two hundred.

The specific influence practices we’ll explore in Part I are:

1) Demonstrating care for colleagues

2) Encouraging others to express objections and doubts

3) Exuding appreciation and good cheer

4) Taking time to develop a shared outlook

Figure I.1: Inviting Participation

![]()

Chapter 1

Be Humane ~ Confucius

Boston: October 1989. Since Monday, I’d been fantasizing about quitting. My employer of nearly one week was The Forum Corporation, a medium-sized corporate training company. My job was to copyedit and produce materials—workbooks, instructor guides, and other bits and pieces—for their sales and management seminars. I sat in a small cubicle farm with several other editors, all of us clicking away on IBM 286 desktops.

My two previous jobs had been at publishing houses, where most everyone had been a task-focused introvert like me. Here at Forum, the culture was different: People beamed and said, “Hey, how are you?” as they passed in the corridors; shouts of laughter came from New England Sales, the office adjacent to the Editing cubicles; meetings began with icebreakers. Moreover, the entire enterprise seemed questionable: teaching people how to sell and manage? Was that even a thing? I felt thoroughly out of place and had decided to stay only until I could find another job in the publishing industry. I already had a few applications out.

It was now 4:00 p.m. on Thursday and I was editing some handouts when my boss, Mona, appeared in my doorway toting an enormous rubber-banded roll of Mylar flip charts.

This was before PowerPoint. For visual aids the class instructors used large, preprinted pads of flip charts, which were produced as follows: an editor compiled the 50-plus charts needed for a workshop, printed them out on the laser printer, and sent the sheaf to a calligrapher; the calligrapher hand-scribed the words and graphics in black ink onto translucent plastic sheets the size of area rugs; a great roll of these so-called Mylars came back for proofreading; assuming there were no errors, the Mylars were shipped off to the printer, whence would eventually emerge a bound set of flip charts for the instructor to use. The whole process took about two weeks, which from today’s perspective seems insanely time-consuming. It had, however, a kind of artisanal charm.

Mona put the roll of Mylars on my desk. “Christine just sent these over,” she said. “It’s a rush. Can you proof them now?”

Our day ended at 5:30 p.m., and I’ve never been good at pivoting. I looked at the foot-thick log, then up at Mona. “I can’t. I’m doing these handouts.”

Mona said, “We really need to get the corrections back to her first thing tomorrow.”

I had an inspiration. “Could I take them home and do them this evening?”

“Of course,” said Mona. “Thanks.” She turned to leave. Then she turned back: “Just one thing. Be careful when you take them home, because . . .”

The next few seconds changed everything. There are many reasons I stayed with Forum for 23 years, but had Mona not said what she said instead of what I expected her to say, I might not have stuck around long enough to give all those other reasons a chance.

What I expected her to say was: “Be careful . . . because those Mylars are expensive.”

That’s the sort of thing managers at my previous jobs would have said. Oh, they weren’t mean people; they were perfectly pleasant, but as managers they were naturally concerned with costs to the firm. I assumed Mona had the same concerns. I was just about to assure her that yes, I’d be very careful not to damage the flip charts, when she finished her sentence:

“. . . because those Mylars have sharp edges. It’s easy to cut yourself.”

In his “Everyday Leadership” TED Talk, Drew Dudley describes the time when, as a university orientation-week coordinator, he gave a lollipop and a friendly smile to a young woman standing in line to register for her first year. Unbeknown to him, she was terrified by the whole scene and had decided college wasn’t for her. She was just about to walk out the door when Dudley’s small gesture changed her mind. She told him the story four years later, at her graduation; the odd thing, he says, is that he doesn’t remember the “lollipop moment.”

I bet Mona doesn’t remember the flip-chart moment, either. To me, though, it made all the difference. It told me this was a place where the first order of business was to care.

The Humane Neighborhood

The Master said, “A neighborhood suffused with a humane spirit is beautiful. How can a man be considered wise when he has a choice and does not settle on humaneness?” (Analects 4.1)*

Caring is also the first order of business for China’s greatest philosopher (see “The Sage: Confucius,” below). In the compilation of his teachings known as the Analects, Confucius speaks of no quality with more approval than ren, which translates as “humaneness” or “benevolence.” Ren isn’t just about being nice; it’s about treating people as ends rather than means, as beings worthy of our concern. The English phrase “neighborhood suffused with a humane spirit” is captured in the Chinese word liren. Li means neighborhood, but (says Analects translator Annping Chin) it could also refer metaphorically to the sphere one travels in, including one’s profession and circle of friends.1 Liren, then, is a sphere of humanity: a community, physical or virtual, where people care for one another.

Why is such a place so desirable? “A person who is not humane cannot remain for long either in hard or easy circumstances,” says Confucius, whereas “a humane person feels at home in humaneness.” (4.2) A humane community, in other words, has stability and resilience. When members of a group feel they belong, they’re likely to stay put and lean in; when they feel out of place—as I did in my first few days at Forum—they spend their time and energy searching for an exit. Moreover, individuals who lack humanity also lack patience and resolve; always on the lookout for a better crowd or more useful contacts, they don’t remain anywhere for long. An inhumane community is perpetually leaking humans.

The Sage: Confucius

Confucius, who lived in the sixth to fifth centuries BCE, remains China’s most-revered moral teacher and one of the world’s most-quoted thinkers. His sayings are drawn mainly from the Analects, a collection of anecdotes and sayings featuring “the Master” and his followers. Compiled by several generations of disciples, the Analects are a record of what Confucius said, not of what he wrote—just as Plato’s dialogues are a record and interpretation of the words of his teacher, Socrates. During much of the first millennium CE, the Analects took a backseat to Buddhist texts that had arrived from India and been embraced by China, but by the thirteenth century Confucianism had returned to center stage and with it the Analects, which became one of four books young men had to know cold in order to pass the civil service examinations that were the ticket to the middle class. “These hopeful aspirants,” says translator Annping Chin, “would memorize the text when they were very young and then return to it repeatedly almost as a daily exercise.”2 The Master would no doubt approve. “Is it not a pleasure to learn and, when it is timely, to practice what you have learned?” he says on the Analects’ opening page.

The value of liren might therefore seem obvious, but in Confucius’ day it wouldn’t have been. People then had a place in society and would typically stay in that place: Farmer Po of North Village would remain Farmer Po of North Village whether the village was suffused with humanity or not. Today there’s more recognition that individuals can pick up and go, hence more talk of employee retention schemes and Best Place to Work awards. Still, mobility can cut the other way, causing employers to see little point in building a sense of community among workers who are here today, gone tomorrow. In all eras, organizational leaders have been inclined to dismiss ren as either unnecessary (“Why bother? It’s not as if these people have anywhere else to go”) or futile (“Why bother? They’re going to leave anyway”). But Confucius saw the benefits of ren and made it the core of his teachings:

The Master said, “Zeng Can, my way has a thread running through it.” . . . After the Master left, the disciples asked, “What did he mean?”

Zeng Can said, “The Master’s way consists of doing one’s best to fulfill one’s humanity [zhong] and treating others with the awareness that they, too, are alive with humanity [shu].” (4.15)

The word zhong is formed from the Chinese characters for “center” and “heart,” and may be translated as “doing one’s best.” Shu is formed from “knowledge” and “heart,” and means “putting oneself in another’s place.”* So, humaneness has two aspects. Zhong is directed inward and consists in knowing and trying to live up to one’s best self: “doing one’s best to fulfill one’s humanity.” Shu is directed outward and consists in seeing the full personhood of others: “the awareness that they, too, are alive with humanity.”

As we encounter more Eastern sages, we will find flowing through their works these same two principles: first, appreciate that you are human; second, appreciate that others are human. This is the moral double-helix analogous to the chemical double-helix that comprises our DNA: the twin silver threads spiraling through all our interactions, rendering them humane.

One more linguistic note: In classical Chinese, the written character for “heart” is the same as “mind.” Zhong, therefore, could also be read as “center-mind” and shu as “knowledge-mind.” The Chinese language doesn’t make the distinction most Western languages make between emotion and reason, feeling and analysis. Heart-mind (xin) is simply the ability to think and act with care: that is, with a sense that the human world matters and that our response to it matters. For Confucius, humaneness requires—to use Western idioms—a warm heart and a cool head. Judgment, informed by tradition and honed by experience, tells us whether to approach a situation with passion, with detachment, or with equal amounts of both.

Confucius also explores what humaneness isn’t. In Chapter 5 of the Analects, a disciple asks the Master what he thinks of three other men in their circle:

Meng Wubo asked, “Is Zilu humane?” . . . The Master replied, “Zilu could be put in charge of military levies in a state of a thousand chariots, but I don’t know if he is humane.”

“What about Qiu?”

The Master replied, “Qiu could be made to assume the stewardship of a town with a thousand households or of a hereditary family with a hundred chariots, but I don’t know if he is humane.”

“And what about Chih?”

The Master replied, “Chih, standing in court with his sash fastened high and tight, could be asked to converse with the visitors and guests, but I don’t know if he is humane.” (5.8)

Zilu, Qiu, and Chih are talented men; their talents, however, are not on a par with humaneness. Zilu is a captain, a bold commander on the battlefield. Qiu is an administrator who could manage the affairs of a thousand households with efficiency. And Chih is a diplomat, navigating delicate negotiations at court with nary a slip of his sash. We know these types, and while they’re more admirable than the baron, the legalist, and the seducer—the three power chasers whom we’ll meet in Part II—they still fall short. Confucius is skeptical about their paths. “Sure, you can be a great captain, a great administrator, or a great diplomat,” he implies, “but don’t imagine you have reached the pinnacle of success. Above you on the mountain stands the real deal: the great human being.”

By this point we may be growing worried that humaneness is out of reach for us mere mortals. Confucius takes pains to assure us that ren consists not of grandiose acts of altruism but of something far more ordinary, something like the spirit present in a happy family. The following dialogue suggests how simple yet elusive that spirit is:

Zigong said, “If there is someone who is generous to his people and works to give relief to all those in need, what do you think of him? Can he be called humane?”

The Master said, “This is no longer a matter of humaneness . . . Even Yao and Shun found it difficult to accomplish what you’ve just described. A humane person wishes to steady himself, and so he helps others to steady themselves. Because he wishes to reach his goal, he helps others to reach theirs. The ability to make an analogy from what is close at hand is the method and the way of realizing humaneness.” (6.30)

Zigong’s view of humaneness, in other words, is a little overwrought. Confucius notes that humaneness is both more difficult and more realizable than “working to give relief to all in need.” Such all-encompassing benevolence is easy to talk about; putting it into action, however, was a stretch even for legendary sage emperors Yao and Shun. But if virtuous talk is not enough, and virtuous action so hard, what are we to do? For Confucius, humaneness requires only that we “make an analogy from what is close at hand”—that we take up the...