- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Integrative medicine is increasingly part of mainstream practice in, for example, palliative care and management of cancer, pain, heart disease and mental illnesses. This book explores the ethos that underpins the Sheldon list - how self-help works, particularly in the realm of chronic conditions. It examines the evidence supporting complementary therapies and how to use them safely. Numerous studies attest to the therapeutic benefits offered by various approaches to augment conventional medicine. The book deals with these topics by focusing only on evidence in the scientific and medical literature.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Holistic Health Handbook by Mark Greener in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Médecine alternative et complémentaire. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The limitations of modern medicine

Better sanitation, clean water, improved nutrition as well as effective and relatively safe vaccinations, medicines and surgical operations mean that we are, in general, healthier than any previous generation. We no longer fear that a scratch could prove fatal, a cough could herald tuberculosis or our children will contract polio while swimming.

And, on average, we live longer than ever. During the seventeenth, eighteenth and much of the nineteenth century, life expectancy was just 30 to 40 years. Government statistics estimate life expectancy for children born between 2008 and 2010 at about 78 years for boys and 82 years for girls. Indeed, 32 per cent of boys and 39 per cent of girls born in 2012 in the UK can expect to celebrate their one hundredth birthday.

However, as mentioned in the introduction, the marginalization of the ‘whole patient’ is a consequence of the same scientific revolution that transformed our health and longevity. Appreciating modern medicine’s limitations helps you understand why you need to take control of your health using a ‘holistic’ approach and helps you work proactively with your doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals to optimize your health. But this raises a fundamental question: what is ‘health’?

The ‘health’ enigma

You know when you’re under the weather: you feel out of sorts, lethargic, run down. The symptoms of many serious ailments are more obvious: angina’s crippling chest pain; flu’s raging fever; the discomfort and disability of a broken limb. Yet defining health and disease is more difficult than you might expect. Indeed, Tikkinen and colleagues note that ‘disease’ ‘can be as difficult to define as beauty, truth or love’.1

Health – the word derives from old English for ‘being sound’ (hoelth) – isn’t simply not being ill. In 1948, the World Health Organization defined health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. The definition underscores that a holistic perspective – encompassing physical, mental and social aspects – is essential for ‘health’.

A fundamental problem

Yet this apparently simple definition raises fundamental problems. Most doctors would regard me as reasonably healthy. My blood pressure and other vital signs are normal. Thankfully, I don’t currently suffer from any serious diseases. I don’t drink excessively or smoke, my diet is reasonably healthy and I exercise fairly regularly. Yet I am constantly niggled by aches, pains and anxieties, and do not have either the time or the money to participate in a ‘full social life’. Even on a good day, I’m a long way from being in a state that I would regard as ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’. In other words, I feel dissatisfied with many aspects of my life.

Worryingly, some studies link ‘dissatisfaction’ with an increased risk of ill health. In one investigation, British civil servants who said they were moderately or highly satisfied with their life were respectively 20 per cent and 26 per cent less likely to develop heart disease (allowing for other risk factors) than those who reported low levels of satisfaction. Indeed, satisfaction with their job, family life, sex life and themselves each reduced the risk of heart disease by around 12 per cent.2 But how many doctors would regard dissatisfaction with your sex life or job as being ‘ill’? Fortunately, as we will see throughout this book, you can change the way you react to life’s frustrations.

The impact of culture

To complicate matters further, patients’ view of ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’ can differ dramatically. A constellation of symptoms that Peter may regard as ‘healthy’ can leave Paul under the weather. Doctors regularly face the worried well: people who fear a minor ache or pain could be the first sign of a serious illness. On the other hand, some people soldier on with remarkable fortitude despite overwhelming physical or mental handicaps. And our attitudes change as we age. Russell points out that some people – particularly young men – tend to regard health as synonymous with fitness. Older people tend to focus on function: whether they are well enough to take part in their work, hobbies and other activities of everyday life.

Society also strongly influences our definition of ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’. In her fascinating book The Cure Within, Anne Harrington notes that Japanese does not even have names for hot flushes (also called hot flashes) or the night sweats experienced by many Western menopausal women. In part, the absence of these symptoms may reflect the fact that female ageing in Japan does not usually carry the same connotations of ‘diminished status and worth’ as in North America or Europe.

The Western menopausal symptoms illustrate that some people express emotional problems by developing physical symptoms – called somatization. For example, Russell notes, depressed people often complain of vague symptoms, such as aches and pains ‘everywhere’, tiredness, headaches and dizziness. In English-speaking countries, our bowels bear the brunt of somatization – we’re ‘sick with fear’, have ‘the runs’ or complain of ‘butterflies in the tummy’. Chinese people complain of somatic symptoms in their liver, spleen, heart or kidneys. In Iran and the Punjab, the heart tends to be affected. These symptoms, Russell points out, offer a ‘socially acceptable way of indicating emotional distress’.

Napoleon’s menstruating men

A striking example of society’s impact on symptoms regarded as ‘normal’ emerged when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt in 1798. Bonaparte found ‘a land of menstruating men’, Russell reports. A parasitic worm – schistosomiasis – can invade the bladder. So, infected patients often pass copious amounts of blood in their urine, inspiring Bonaparte’s comment. Even today, young boys in rural Egypt sometimes jump in the red urine of infected people to catch a ‘disease’ they regard as ‘normal’.

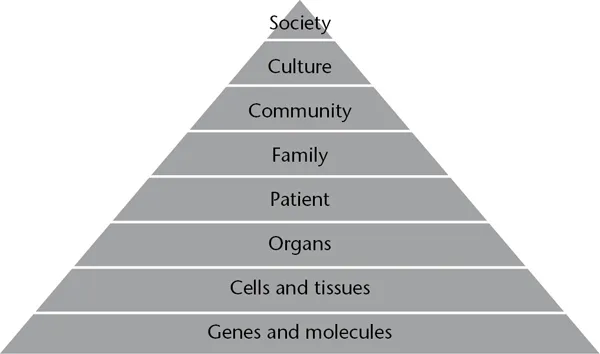

Given the multitude and diversity of factors that influence health and disease, it’s not surprising that doctors strip away the social, subjective and emotional elements leaving a core of scientifically identifiable and treatable ‘abnormal’ biology. Essentially, doctors focus on the levels in Figure 1.1 from ‘patient’ down. For example, mould in poor housing commonly triggers asthma. Unemployment, debt and economic uncertainty can increase the risk of heart disease and psychiatric illness (page 17). Understandably, doctors tend to alleviate symptoms with drugs rather than try to improve housing or tackle the country’s economic woes. (Nevertheless, GPs often refer people to medical social workers to help with benefits and other support services.) But, in some people, tackling the symptoms and not the causes papers over the cracks.

Figure 1.1 A hierarchy of systems influences health and well-being

Source Adapted from Russell

The foundation of modern medicine

Modern medicine is objective, rational and scientific. Doctors use objective signs (e.g. blood pressure and heart rate) and symptoms (e.g. pain or a rash) to diagnose and prescribe. They evaluate a treatment’s success based on measurable changes – such as a reduction in blood pressure or cholesterol level, or an obvious improvement in symptoms. Furthermore, as Roberta Bivins notes, a ‘potent combination’ of laws, regulations, commercial and political interests, culture and public expectations support and sustain this biomedical approach. And the biomedical approach is our most powerful technique to identify the medicines that we rely on. Russell notes that in any 24 hours about half of all adults in the UK probably use a prescribed drug.

Nevertheless, Exploring Reality, a thought-provoking and inspiring book by John Polkinghorne (a theoretical physicist who became an Anglican priest), notes that ‘science describes only one dimension of the many-layered reality within which we live, restricting itself to the impersonal and general, and bracketing out the personal and unique’. In particular, Polkinghorne adds, the biomedical approach ‘has difficulty accounting for psychological, sociological, and spiritual factors that influence most, if not all, illnesses’.3 Holistic approaches restore the ‘personal and unique’ by encompassing the psychological, sociological and spiritual factors.

Indeed, Polkinghorne notes, complex systems – such as the human body – generate patterns of effects that studying the individual components would not predict. (The technical term for these patterns – which may include consciousness and life itself – is ‘emergent phenomena’.) For example, we know that certain parts of the brain seem to change in alcoholic people. We know the chemical processes that the body uses to break down alcohol. We know that around 50 to 60 per cent of the risk of developing alcoholic liver disease or becoming addicted to drink depends on the genes you inherited from your biological parents.4 But that’s a long way from examining the systems and knowing who will develop a drinking problem, how much they will imbibe on a particular night and their chances of recovery.

And while science is capable of profound insights and stimulating remarkable technological advances, medicine still cannot explain how every effective treatment works. A paper in the prestigious Archives of Internal Medicine considered 31 studies – which included almost 18,000 patients – and reported that acupuncture roughly halved the intensity of chronic pain caused by back, neck and shoulder pro...

Table of contents

- About The Author

- Overcoming Common Problems Series

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 The limitations of modern medicine

- 2 The mind in medicine

- 3 The spirit in medicine

- 4 Four steps to help your inner healer

- 5 Complementary therapy: supporting your inner healer

- 6 Your companions for health

- 7 Resilience and the road to recovery

- Useful addresses

- References

- Further reading

- Search terms