1

Knowing your body

Understanding your menstrual cycle and fertile window

When I first started working in the fertility field in my twenties, I was very aware that many of my friends did not understand their anatomy, menstrual cycle and fertility. Since that time, I have wanted to help women be in tune with their bodies, especially during their reproductive years. At school we might learn the basics about puberty, how not to become pregnant and how to avoid catching a sexually transmitted infection, but that is about it. And some schools do not teach anything at all.

For decades we have had access to contraception and sexually transmitted infection clinics, but not clinics that evaluate, monitor or educate men and women about their reproductive health. Women might discuss these topics with their friends, but talking about ‘women’s issues’ is still taboo. Chances are, women are going to search online for any questions they have. Or they might read about the topic in magazines and on websites. But is this information really reliable?

I am on a mission to help women understand their bodies, especially during their reproductive years from the menstrual cycle to the menopause. I want to help you understand your body, your fertility and the scientific evidence behind your menstrual cycle.

Your body: inside and outside

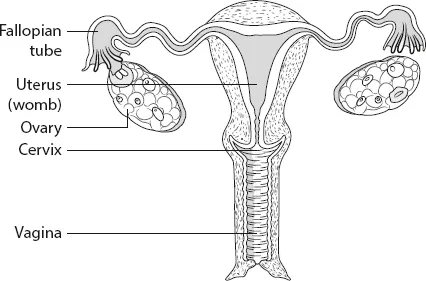

The female reproductive system is made up of two ovaries, two Fallopian tubes, a uterus (womb), cervix (neck of the womb), vagina and vulva (external genitalia) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The female reproductive system

Let’s start by discussing the external parts of the reproductive system.

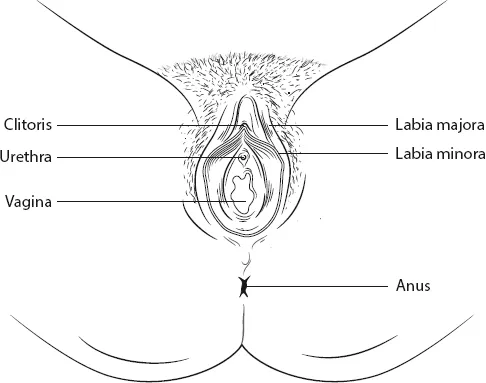

We need to normalize the words for the female reproductive system. Vulva and vagina are not offensive words, so let’s use them correctly. The term ‘vagina’ is often used incorrectly. Vagina refers only to the muscular tube leading from the external genitals (genitalia) to the cervix of the womb (uterus). Most people use vagina to refer to the woman’s external genitalia, which is actually called the vulva (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Female external genitalia

The vulva is made up of the clitoris, urethra (which leads to the bladder and allows for the passage of urine), and the labia majora and labia minora (these are the fleshy lips of the vulva) (Figure 1.2). Women have three openings: the urethra for urine, the vagina for menstrual blood, intercourse and delivery of the baby, and the anus for faeces.

Some people feel uncomfortable talking about their genitalia, and it is likely that many women have never seen another woman’s vulva and may not even have seen their own! It is important for women to understand that no two vulvas or vaginas will look the same. Figure 1.3 shows some images of female genitals, highlighting how different we all are.

Figure 1.3 Vulvas are all different

Unfortunately, today’s easy access to pornography often portrays unrealistic images of the female anatomy, where the women involved may have been surgically altered, including labial reduction (Chapter 4). This may make women feel there is something wrong with their genitals.

There is a growing market in vagina/vulva surgery and a growing list of products and procedures to allegedly improve the appearance and health of women’s genitals. Girls as young as nine have requested labial reduction. I heard that one woman said she could not go to the gym as her labia were too large, and another said she would not get a boyfriend until her labia were reduced.

My colleague Professor Sarah Creighton has studied labial length and width between women who requested labial surgery and women in her gynaecology clinic who were not requesting surgery and found no difference in their labia.1 Why do the women requesting surgery feel their labia are abnormal? I am sure some of this is due to the images they see in porn, but I wonder if women are more aware of their external genitalia as shaving pubic hair is common. Some women claim they experience chafing and irritation of their genitals, which again could be because they are totally shaved.

The labia are full of nerves, and surgery may cause damage which could affect the chances of orgasm. The risks of labial surgery are infection, scarring causing numbness, and reduced sensitivity of the genitals. There is also an increasing demand for procedures available at a ‘vaginal spa’ which include vaginal steaming or lasers to rejuvenate your vagina and the insertion of jade eggs, Luna Beads or vaginal detox pearls/beads into your vagina! I would not recommend any of these procedures.

Vagina/vulva hygiene is obviously important, but the genitals are self-cleaning. It produces natural secretions which maintain natural health. The vagina/vulva has its own ecosystem (the vaginal microbiome), which is made up of good bacteria and other beneficial microorganisms, and it has a specific pH. We should use only water and mild, unscented soap around this area, and we should not push any fluids up the vagina. Using chemicals or procedures that upset the good bacteria can cause problems. If you have any health concerns about your genitals, please visit your doctor.

Inside our bodies, each ovary sits close to a Fallopian tube, and both Fallopian tubes connect to the womb (Figure 1.1). The Fallopian tubes are about 10–12 cm long and 1 cm in diameter. The base of the womb is called the cervix and extends into the vagina. The womb is about 7–8 cm high, with a width of about 5–7 cm. It is about 2–3 cm thick and is made up of three layers of cells: the perimetrium, myometrium and endometrium. The womb is held in place by ligaments. The endometrium changes in thickness and characteristics throughout the menstrual cycle and is shed during menstruation. The ovaries consist of fluid-filled sacs called follicles, which contain immature eggs.

Hormones are needed for the eggs to grow, mature and ovulate each month from puberty to the menopause. At ovulation, the egg is captured by the Fallopian tube. During sexual intercourse, the sperm is deposited at the top of the vagina and swims through the cervix, through the womb and down the Fallopian tube where it hopes to meet an egg. If the sperm fertilizes the egg, the Fallopian tubes will carry the embryo towards the womb. It is here that the embryo will implant, attaching to the lining of the womb, where it connects to the mother’s blood supply and will remain until the baby is born.

The male anatomy corresponds to the female anatomy, as we are made from the same basic structure (Table 1.1). The ovaries correspond to the testes, the penis to the clitoris, and the labia to the scrotum.

Table 1.1 Comparison of male and female anatomy

| Male | Female |

| Testes | Ovaries |

| Part of the testis | Womb, Fallopian tubes |

| Glans and shaft of penis | Glans and shaft of clitoris |

| Part of the penis | Labia minora |

| Scrotum | Labia majora |

When a girl is born, the vagina is normally covered by a thin piece of skin called the hymen. The hymen allows menstrual blood to come out from the vagina, but is usually ruptured if something is inserted into the vagina, such as a penis, finger or tampon. When it is first ruptured, a small amount of blood may be shed, but this is not always the case. The hymen can also be ruptured through doing sports such as horse riding and gymnastics.

What happens during our menstrual cycle?

The two key events of our menstrual cycle are having a period and ovulating.

At puberty, girls start their periods. It can be a difficult conversation to tell a young girl that she is going to bleed every month from her vagina. From puberty onwards, a girl will usually have a menstrual cycle every month. But every woman is individual and there are huge variations in the length of women’s menstrual cycles, how long they bleed for, how heavy their periods are, how painful they are, and whether they experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

Women have menstrual cycles for about 40 years of their lives. Worldwide, about 800 million women are having their period right now. Most women have a period approximately every four weeks from their teenage years until they reach their fifties. During our fertile years, we menstruate for around 3000 days and our lives are governed by our menstrual cycle. During this time, if we are sexually active, we are either trying to become pregnant or trying to avoid pregnancy. In many cultures, discussing menstruation is taboo and sometimes women are isolated from the rest of the community during menstruation because they are seen as impure. Globally, many women have no access to period products. For those who do, during their lifetime they will spend a fortune on these products.

The menstrual cycle affects every woman’s life in some way, physically, emotionally or both. As well as bleeding, some women have to cope with PMS and painful periods. In some cases, this can affect their education or professional life.

Most of what we know about the menstrual cycle has been established from studies of women who have regular 28-day cycles with a normal body mass index (BMI). Textbooks tell us that women have 28-day cycles and ovulate on day 14. I have been doing research with Natural Cycles, a company that makes a contraception/fertility app. The Natural Cycle App allows women to track their menstrual cycles and fertile window. In one study, we looked at over 600,000 menstrual cycles and found that menstrual cycle length varied from 15 to 50 days.2 Only 13 per cent of the women had a textbook 28-day cycle – the rest had either shorter, longer or more variable cycles. This study and other recent studies have changed our understanding of the menstrual cycle.

Many women think that a normal menstrual cycle should be around 28 days. In fact, menstrual cycle lengths of anywhere between 21 and 35 days are considered normal. Anything less than 21 days is considered a very short cycle, and anything more than 35 days is considered a very long cycle.3 Some women have regular cycles, others have irregular cycles. No matter what sort of menstrual cycle you have, there will be someone else out there who has a very similar experience to you. If you have irregular cycles, you may experience fertility difficulties when you try for a baby (Chapter 9).

The first day of the menstrual bleed is counted as day 1 of the cycle. Menstruation is caused by the shedding of the womb lining when a pregnancy does not occur and our body starts a new cycle. A period can last for 3–7 days but this varies between women. In our Natural Cycles study, the average period length was 3.8 days.

During a period, women usually shed only about 6–8 teaspoons of blood, but may shed up to 16 teaspoons (80 ml). A period pad or tampon should be changed every 3–4 hours.

In a 28-day cycle, days 1–14 are called the follicular phase. During this time, several follicles containing eggs grow as they become filled with fluid. But only one follicle will fully mature. The specialized cells in the follicles, called granulosa cells, produce oestrogen to help the egg mature. When the final maturation is achieved the egg is released from the ovary during ovulation. Textbooks tell us that ovulation takes place around day 14, but the day of ovulation varies depending on how long the cycle is. In our study with Natural Cycles, we found the average day of ovulation was day 17, but this ranged from day 10 to day 26 depending on the cycle length. As expected, women with shorter cycles ovulated earlier, and those with longer cycles ovulated later.

The two weeks after ovulation is called the luteal phase. This is when the womb is preparing for implantation of the embryo. The empty follicle is now called a corpus luteum (hence the luteal phase) and it produces progesterone. Progesterone acts on the lining of the womb to prepare it for implantation. If an embryo implants, the woman will not have another period; instead the embryo will continue to grow and develop into a fetus. If implantation does not occur, the woman will have a period around 14 days after ovulation and this marks the start of another cycle.

What is the science behind the menstrual cycle?

The menstrual cycle is controlled by hormones which rise and fall at different times (Table 1.2, Figure 1.4). The eggs contained in the follicles on the ovary are immature. The hormones enable the eggs to mature, allow ovulation (usually of just one egg per month) and prepare the womb for the implantation of the fertilized egg.

Table 1.2 The main hormones involved in the menstrual cycle

| Hormone | Abbreviation | Produced by | Function |

| Gonadotropin-releasing hormone | GnRH | Hypothalamus | Stimulates the production of FSH and LH |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone | FSH | Pituitary | Stimulates the egg in the follicle to grow and mature |

| Luteinizing hormone | LH | Pituitary | Causes the final maturation of the egg. Ovulation wi... |