![]()

1

A history of the Alexander Technique

In this chapter you will learn:

- about the man himself – Frederick Matthias Alexander

- how he came to formulate his technique and how it worked for him

- his early history and how he became an actor

- the problems he suffered doing his one-man shows.

If people go on believing that they ‘know’ then it is impossible to eradicate anything – it becomes impossible to teach them.

F.M. Alexander

To understand the Alexander Technique fully it is essential to know how and why it came about. You may be tempted to skip this chapter, but I would seriously recommend that you don’t. Without knowing who Frederick Matthias Alexander was and how he developed his Technique, you could miss a lot of vital clues as to how it works.

Most books that concern therapies of one sort or another include case histories, but for the Alexander Technique the best case history is the man himself.

Insight

Frederick Matthias Alexander formulated the Alexander Technique as a result of his search for a solution for his persistent breathing and voice problems. Even as a young child he suffered from breathing problems. The Alexander Technique is not just for back problems but also has a profound effect on breathing problems, such as asthma, and a host of other ailments.

Alexander’s early history

Alexander was born into a poor family in Wynyard, Tasmania, in 1869. He was the eldest of eight children and grew up on a remote farm in north-west Tasmania. As a child he was weak and sickly and suffered from continual breathing problems. Today he may well have been diagnosed as asthmatic. At times he was too ill to attend school and was kept at home where he managed to learn whatever he could. Naturally, being at home a lot led to him growing up isolated from other children. From an early age he was individualistic and unorthodox and was labelled at that time as precocious.

From the age of about nine his health began to improve although he continued to stay at home. He began to learn how to manage horses, which his family bred, exercising them and training them. A passion for horses stayed with him throughout his life. He also began to show an interest in the theatre – it seemed a natural path for someone as confident and outgoing as Alexander to follow. Remember it was the 1870s, there was no television, not even radio, and he lived on a farm a long way away from the nearest neighbours, with seven younger brothers and sisters. What could be more natural than for him to become the entertainer for their benefit? Alexander discovered Shakespeare around this time and began to learn how to recite his favourite speeches. He set his heart on a life as an actor but in 1885, when he was still only 16, the family suffered a series of disastrous financial setbacks and Alexander had no choice but to look around for a regular job.

A YOUNG MAN IN MELBOURNE

Alexander had to take whatever was offered and found himself in the mining town of Mount Bischoff – as a clerk in a tin mine. Somehow he managed to stick at it, sending money home regularly, until three years later when he had managed to save enough to get himself to Melbourne. By now the family’s fortunes had revived somewhat and Alexander was able to use his savings to rent board and lodgings in the city and to pay for acting lessons. He also discovered a new passion for music.

He was 19 years old and living in a big city for the first time. He entered into the spirit of his new life completely. He went to the theatre as often as possible, mixed with other actors, visited art galleries, attended concerts, and even managed to organize his own amateur dramatic company.

CASUAL WORK

These were exciting times for the young actor. When he ran short of money he took casual jobs as and when he could find them – as a bookkeeper and a clerk, a store assistant and a tea-taster. He never managed to keep any job for very long for three reasons. First, he despised what he called ‘trade’; second, he suffered from a short fuse and a fairly violent temper; and third, he couldn’t be bothered to dedicate himself to any job for the simple reason that he knew he was going to be an actor – and a good one.

Insight

During his early twenties Alexander had established himself as a fine young actor with a considerable reputation. He developed a one-man show that was a mixture of dramatic and humorous recitals, but his speciality was still his Shakespearean presentations. Apart from his constant bouts of ill health, due again to his breathing problems, he was enjoying the beginnings of a successful and rewarding career as an actor.

SPEECHLESS

As his popularity began to grow and he was called upon more and more to give his one-man show, he began to suffer from a complaint that seemed utterly disastrous for an actor – he lost his voice.

The first few times it happened he was able to rest for a day or two and, when he had recovered his voice, he could continue with his shows. But the problem not only persisted, it actually began to get worse. He tried all the usual remedies of doctors’ prescriptions and throat medicine but nothing seemed to work. The more shows he did, the worse his voice got. He went to various voice teachers and doctors and the only cure was complete rest.

He gave up speaking completely, on one doctor’s advice, for two weeks. At the end of the fortnight his voice was back to normal and he gave a show that evening. Half-way through the show his voice went completely and he was forced to abandon the performance. The same doctor recommended that this time he give up speaking for a month. Alexander was not impressed. ‘Surely,’ he asked, ‘if my voice was all right at the beginning of the show but let me down half-way through then it must have been something I was doing that caused it to go?’ The doctor thought he might well be right but was unable to offer any further help.

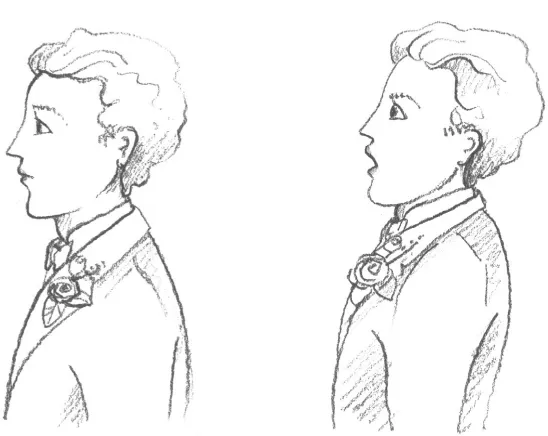

The manner of doing

Alexander took to watching himself in a mirror as he rehearsed to see if there was anything he was doing that was causing the voice loss. He knew his ordinary speaking voice was not affected – it was only when he was reciting that the voice loss was triggered. He watched himself in the mirror as he spoke normally and again as he recited. He noticed that while he spoke normally nothing much happened, but that just before he began to recite he did three things: he tensed his neck causing his head to go back, he tightened his throat muscles, and he took a short deep breath. As he recited he noticed that he did these three things constantly, even exaggerating them quite wildly at times as the passion of his acting overtook him. But this was how he had been trained to project his voice as a professional actor. He found that even when he spoke normally he was still doing these three things but on a much smaller scale, he just hadn’t been able to see it before (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 F.M. Alexander noticing his problem.

Insight

As a result of observing himself in specially positioned mirrors Alexander observed the following three things:

- He had a tendency to pull his head back and downwards thus tightening the muscles at the base of his neck.

- He tightened his throat muscles.

- He took a short deep breath.

Alexander was observing what he called his manner of doing.

Once he had seen his manner of doing he thought, quite rightly, that if he was able to stop doing the three things then his voice must improve. And he thought it would be easy to stop doing them. But he was wrong. He managed to stop tensing his neck but when he tried to control the tightening of his throat muscles or the sharp intake of breath just before he began to recite, he was unable to break the habit.

Not doing

Unable to correct his habits, he was unable to rectify the problem. He decided that he would take it one step at a time, beginning with the neck tensing because he found he could control this – and this is where he made the discovery that was to lead to the Alexander Technique. He found that if he didn’t tense his neck and stopped trying to correct the other two faults they disappeared on their own. By not doing he managed to do. He realized that by not doing he was making a conscious choice to do. This is the basic fundamental principle behind all of his subsequent teaching. This choice, he reasoned, was responsible for the quality of his performance. He called this capability of choice use.

Insight

Alexander discovered that the more he tried to correct his habits, the worse he could make it. But as he practised his principle of not doing his voice improved and he was able to work normally.

He wanted to take this discovery further and practised putting his head forwards, as he had observed that by tensing his neck it was pulled backwards. He thought that if he put his head forwards he might improve his voice even more. While doing this he noticed, in his mirrors, that as soon as he put his head forwards he again tightened his throat muscles causing his larynx to constrict, and he also lifted his chest, narrowing his back which made him physically shorter. By merely putting his head forwards he changed his entire body shape and tension.

Primary control

He realized that this tension throughout his body influenced everything about him. His voice was not the problem, how he stood was not the cause, and trying to correct it all was not the cure. What he had to learn to do was not to do. He knew that if he put his head up and forwards he could maintain his acting voice indefinitely. All he had to do was not tense anything. Again he used mirrors to make sure he was doing exactly what he wanted to and this was when he made his second most important discovery. By observing himself he realized that when he thought he was putting his head up and forwards he was actually not doing that. He was still pulling it back.

He knew he had to do two things: prevent the movement ba...