![]()

Part one

Handwriting problems

What is good handwriting?

Good handwriting is above all legible.

Then it is flowing, it is consistent and has a distinct character.

Handwriting is an expression of individuality.

Different people have different handwriting.

![]()

1

Self-diagnosis

How to begin diagnosing your writing problems

Some faults can be detected just by looking at a finished piece of writing. So take an example of something you have already written. Do not write or select anything specially for this purpose. Just pick up an old letter, some notes, or even a shopping list – something quite ordinary. Ask yourself these questions:

- Are the basic letters constructed properly, or are they poorly shaped, making the writing difficult to read?

- Do the letters join up and flow?

- Are the strokes leaning in all directions?

- Is the writing consistent?

- Is it mature enough?

- Is it too complicated or fussy?

- Is it too large or too small?

- Is the writing itself quite good but the layout and spacing unsatisfactory?

Now for the diagnosis and where to find the cure:

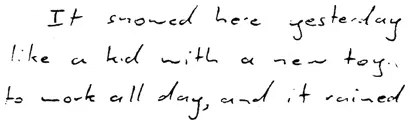

1 If your individual letters are not properly formed your writing may be difficult to read. Perhaps your a’s and g’s are left open so they can be confused with u or y. Maybe you do not finish one letter before starting the next so an n looks like an r, or an a like an o.

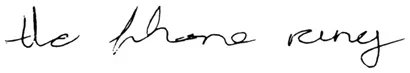

‘The phone rang’. This writing is bad. The a is so misshapen that you are likely to misread the word. Most of the letters are badly formed.

Perhaps there is no difference between your arched letters so that u and n can get muddled up.

Chapter 8 provides a model that you can use to retrain the shape of your letters. We explain there how and why it works. Choose the family or families of letters that you need most.

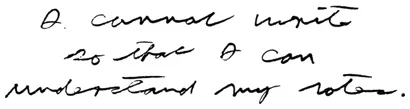

‘I cannot write so that I can understand my notes.’ These letters are so poorly formed that it is not surprising that the writer can hardly read his own notes.

Maybe you start your letters at the wrong point or you make your strokes in the wrong direction, with the result that you find problems when joining up your writing. You might have a personal shorthand that no one else can read because your joined-up letters form unrecognizable symbols. Instead of

you might be getting

. You could be losing a stroke for the same reason.

and

lead to

and

instead of

and

. These problems are more difficult to cure, as you will have to retrain your writing movement. First of all study the analysis of the individual letters on pages 74–99. The point of entry and direction of each stroke is shown. Read

Chapter 8 carefully. Remember to use stroke-related groups of letters when you start practising. Then you are repeating, comparing and improving similar shapes and thoroughly training in the correct movement.

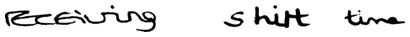

The rounded v in ‘receiving’ reads clearly. The same shape representing ‘ir’ in ‘shirt’ is confusing. ‘Time’ reads as ‘tine’.

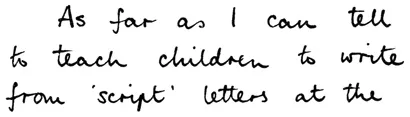

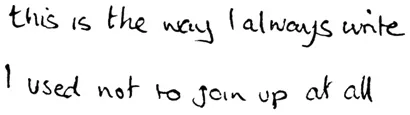

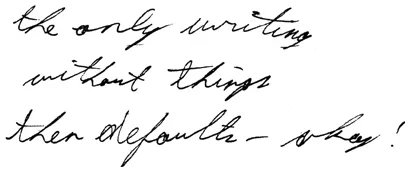

This girl wanted to join up but found if difficult to change from straight letters to a flowing movement.

2 If the letters do not join up and you want to develop a more cursive (joined) writing then you might have to exercise quite hard to change your writing movement. The neater you print the more difficult you may find it. This is because your hand will be accustomed to producing the pressure pattern as well as the shape of the abrupt letters. To join up you have to change direction on the baseline and relax the pressure at the same time. However, it is well worth the effort. Separate letters can seldom be as fast as joined ones or look as mature. Do not go to the other extreme. Too many joins are as bad as too few. The way we hold our pens and rest our hand on the table to write means that we need penlifts every few letters.

When you follow up with the personal modification exercises in Chapter 10 you may find that the angle of your handwriting has changed. As you relax and speed it up you may develop a more forward slant.

The Australian who wrote this went back to a quick print because he could not speed up the complicated cursive that he had been taught at school.

3 If the letters are leaning in all directions there can be several reasons:

- Maybe you have trouble in controlling your pen and keeping lines parallel.

- Maybe you were taught a mixture of styles and you have ended up using a bit of each.

- Maybe you are over-tense. This can affect your writing, pushing your strokes aslant.

- Maybe your joining strokes are at fault. They can come up at different angles from the base of your letters. Then they affect the next upright stroke. This also happens when you do not finish off one letter properly before starting the next.

All these faults will make your writing increasingly hard to read as you speed it up.

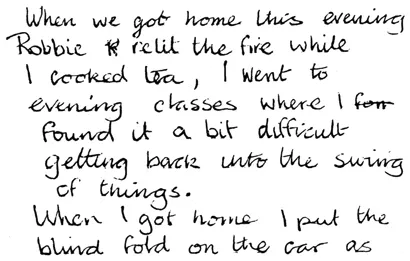

These letters are falling about in all directions. The effect is disturbing, and difficult to read.

This is the only time that we suggest using the exercises as a complete course. Work through the book from Chapter 3 to Chapter 10.

The relaxing exercises on page 25 will help with any tension. You may not need the control exercises (pages 53–4), but they certainly will not do you any harm.

4 If your writing is not consistent first make sure that you are giving yourself the best possible writing conditions. Is the writing the same at the top of the page as at the bottom? Are your letter shapes the same even from one line to the next? If not, read Chapter 3 on practical matters. Pay special attention to what you write with and what you write on. Your posture is important, and where you place your paper too. Chapter 7 on rhythm and texture will also be useful.

In this writing both the joining and the slant are inconsistent.

Maybe you have been taught a style that does not suit you. The model in Chapter 8 will help you to understand more about letters. You will be in a better position to judge what sort of writing you want. Remember that no imposed style is as consistent as a natural writing style.

Aim for regular pressure and smooth flow. If necessary, make more pauses to avoid overtiring your hand. Perhaps try writing a little slower for a while. Tiredness and tension show up in your writing. They often make it uneven.

If you are at a stage in life when you are changing and developing, this will be reflected in your handwriting. It will be variable too until you settle down.

5 If it is not mature enough you may feel that your writing does not present you to others as you would like it to – or even as you are.

Writing can look immature for a number of reasons. Some people remain too long on, or keep too close to, a taught model. Unjoined writing can also look childish. Sometimes large writing can give the same impression.

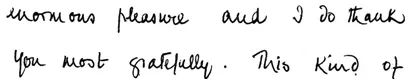

This example lacks the personal modifications that would make it a more mature script. Some people find it hard to develop a personal hand. They stick closely to what they were taught in primary school. They were often praised for their neat handwriting and even won prizes for it. Their writiing might be neat but it remains rather childish.

If you want to develop more mature writing, first try changing pens. Experiment with all kinds to see what suits you best (see page 26). Use the training model in Chapter 8 to improve your letterforms. Chapter 9 will also be necessary for you if you need a more flowing hand. Then pay special attention to Chapter 10, which is all about personal modification of letters and joins. Do not go to the other extreme and try to develop too elaborate a writing. This will not look mature at all, only fussy and affected. Stop worrying about your writing. Practise, and you should become consistent in a natural style that reflects your personality.

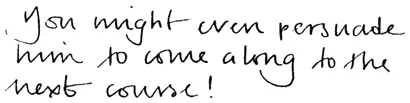

This would be rather too intricate for most people.

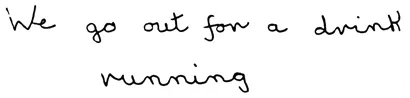

6 If it is too complicated, simplifying your style will gain you speed and legibility. You may have developed unnecessary flourishes or twirls in your writing. They can be difficult to discard, but it is worth trying. They can slow you down and make your writing difficult to read. To other people they often look foolish.

At school you may have been taught a looped cursive that is based on copperplate. The letters are all meant to join up, so your hand cannot be moved along during a long word. At speed the loops often deteriorate into a tangled mess. By the end of a long word you cannot read a thing...