![]()

CHAPTER 1

• • • • •

CREATE POWERFUL INSIGHTS THROUGH CRITICAL REFLECTION

The first thinking and behavior strategy is the concept of critical reflection. In fact, all the executives I interviewed for this book exhibited reflective thinking and practices as part of their mental models (their beliefs, perceptions, and principles) that assisted them through unfamiliar challenges. The adult development and learning theorist Jack Mezirow defined critical reflection as the “ability to unearth, examine, and change deeply held or fundamental assumptions” (Mezirow, 1991). Essentially, to conduct critical reflection, you must apply a concerted effort to challenge your own assumptions and routine ways of thinking to form a new behavior or action. The act of critical reflection is not merely a look backward at past events to pave the way forward with a different decision; rather, you need to integrate a full situational understanding of the past to create a new learned behavior and action. The ambiguity mindset goal is to determine that, while being an expert in your field is a professional achievement, you need to uncover the hidden beliefs that keep you in a limiting comfort zone.

Atul Gawande wrote the article “Personal Best” in 2011 for The New Yorker about his experience working as a surgeon and seeking performance coaching advice. Atul was mindful of his successful surgeries over the previous eight years, as he tracked his results with the national database and consistently beat the averages. In recent years, however, Atul had noticed that his rate of quality care, a measurement of medical issues, was no longer going down, as it should. He wondered whether he had reached his professional peak.

Atul noted that sports athletes, musicians, and actors used performance coaches, and even executives are now comfortable using executive coaches. He wondered why doctors did not use them. He knew that seeking guidance was a risky move. The general perception was that, once you become a doctor, you are the master of your craft, and having a performance coach might be seen as a weakness or lack of expertise. Atul was aware that he might receive harsh judgment from his peers, which could affect his career. But he considered the alternatives and decided to contact an esteemed retired general surgeon, Dr. Osteen. Atul had worked under him during Atul’s residency training. Dr. Osteen agreed to watch Atul’s surgeries and provide feedback.

The retired general surgeon attended one of Atul’s surgeries, and while he watched silently throughout the entire procedure, he provided small but insightful comments in the doctors’ lounge afterward. Dr. Osteen had noticed that Atul had positioned the patient perfectly in front of Atul but not in a position that suited the other surgical attendees. This resulted in the surgical draping being askew for the surgical assistant across the table, on the patient’s right side; this restricted the surgical attendee’s left arm and hampered his ability to fully see the surgical wound.

At one point, the surgical team found themselves struggling to see high enough into the surgical area. The draping also pushed the medical student off to the surgical assistant’s right, where he couldn’t help at all. Additionally, Atul should have made more room to the left side, which would have allowed the surgical assistant to hold the retractor and free the surgical assistant’s left hand. Further feedback included that Atul’s elbows periodically rose to the level of his shoulders, which means less precision and unnecessary fatigue.

Finally, Dr. Osteen observed that Atul was wearing magnifying loupes to ensure a laser focus on the patient, but Atul did not seem to be aware of how much of his peripheral vision was affected. This resulted in Atul’s inability to monitor the anesthesiologist or how the operating light had drifted away from the surgical area.

It is a humbling experience to be an expert in your field and be open and honest enough to invite performance feedback into your practice, but Atul described the experience as enlightening and stated, “That one twenty-minute discussion with Dr. Osteen gave me more to consider and work on than I’d had in the past five years” (Gawande, 2011). By challenging your own and other people’s assumptions through a variety of mechanisms, you can reach outside of your own “I am an expert” mindset. By channeling critical reflection, you must challenge yourself by asking probing questions of your past experiences and thinking patterns to provide a better cognitive framework when faced with hidden barriers or uncertainty in the future.

HIDDEN BARRIERS

Not surprisingly, the concept of critical reflection creates paradoxical tensions, as many fast-paced companies are programmed to keep moving forward and to disregard past events, bulldoze through perceived barriers, or disregard recurring issues to meet the annual or quarterly targets. Interestingly, various cognitive mechanisms work against you that create potential barriers to conducting accurate critical reflection, such as the Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve, which indicates that the speed of forgetting will increase when you endure physiological factors such as stress and lack of sleep (Loftus, 1985). Trusting your memory may not be the best mechanism when you are faced with stressful ambiguous situations.

Neuroscience may also be against you. Research shows that your brain is biased; you may unconsciously downplay past painful experiences or blur them from your memory to protect your self-confidence. Your memory of good experiences may also be flawed, as you tend to see your past good moments as more impressive than the events actually were. And finally, in your recollection of the past event, you may fail to recall additional external elements or may lack a full 360° review of the situation.

Even if you are absolutely sure of your expertise as a seasoned executive with years of successful progression in your career, research supports the need for critical reflection. For example, the overconfidence bias is the tendency to overestimate your abilities and talent. A 2018 article in PLOS journal included a study in which 2,821 participants were asked to rate the statement “I am more intelligent than the average person,” and the results (in part) showed that 65 percent of participants believed they were smarter than average, with more men likely to agree than women (Heck et al., 2018). Additionally, Dr. Tasha Eurich, an organizational psychologist and principal of the Eurich Group, conducted a research study with more than 3,600 leaders across a variety of roles and industries and found that, relative to lower-level leaders, higher-level leaders more significantly overvalued their skills (compared with others’ perceptions) (Eurich, 2018). One of the research explanations is that high-level leaders simply have fewer people giving them candid feedback.

Similarly, David Dunning and Justin Kruger, social psychologists from Cornell University, developed the concept of the Dunning-Kruger effect, which is a type of cognitive bias that causes people to overestimate their knowledge or ability, particularly in areas where they have little to no experience. This may be a valid concept to remember when working in uncertainty and ambiguous situations. The Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that, when you don’t know something, you aren’t aware of your own lack of knowledge and may exaggerate your competence. In other words, you don’t know what you don’t know, and you don’t even know it.

A DELIBERATE PAUSE

To avoid the double burden of a lack of awareness and a lack of experience with uncertainty, the act of critical reflection allows you to take a deliberate pause and helps you think through messy situations. Taking a deliberate pause is crucial for your own self-development; it gives you time to reflect, to seek feedback, to consider alternative views, and to uncover hidden assumptions. Embracing critical reflection to generate new insights leads to becoming better at articulating questions, confronting bias, and examining cause-effect situations.

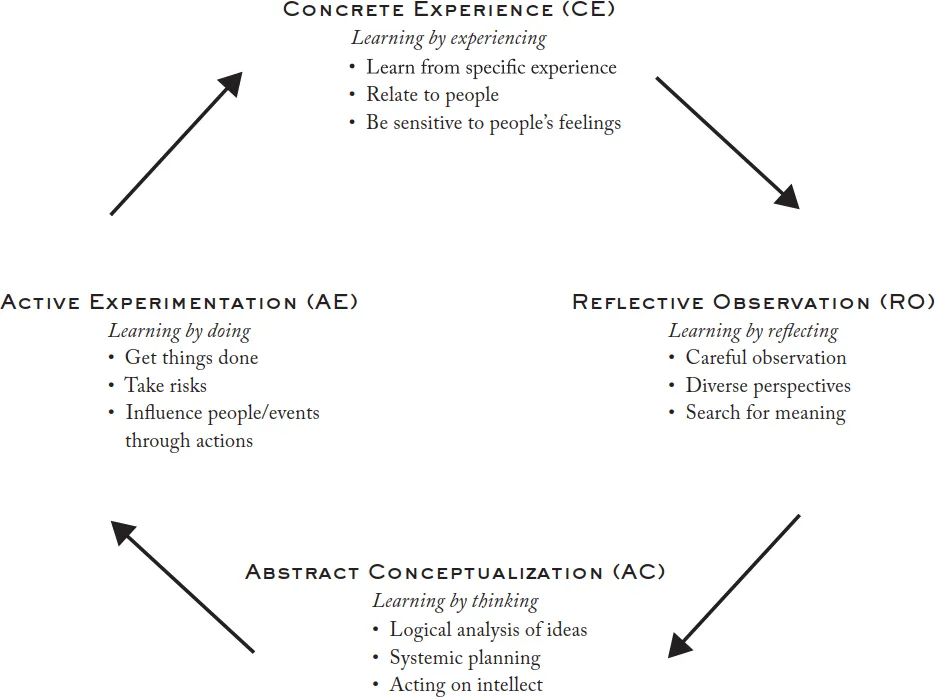

Adult learning theorists are continuing to explore the ways in which reflective practice can increase understanding, expand one’s perspective, and improve learning outcomes. David Kolb, a psychologist and educational theorist, developed a four-stage cycle of learning that incorporates the reflective process as a fundamental component (Kolb, 1984). Kolb’s model is widely used in leadership and education programs and is a key source for understanding how adults learn through discovery and experience.

David Kolb’s experiential learning cycle also provides a useful way to describe how you may gravitate toward a specific way of learning, but more importantly, it can provide a process for a continuum of learning through experience. As illustrated by Lauren Wolfsfeld and Muhammad M. Haj-Yahia in “Learning and Supervisory Styles in the Training of Social Workers,” Kolb’s continuous learning process includes four parts: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. KOLB’S LEARNING CYCLE

(SOURCE: WOLFSFELD AND HAJ-YAHIA, 2010, P. 71)

Dr. Aamir A. Rehman is a partner in an investment firm and conducted a qualitative research study with fifteen private equity professionals who worked in high-stakes environments, in which decisions can result in millions of dollars in gains or losses for the firm. The purpose of the research was to learn how the private equity professionals described the role of learning from experience in their work. He wanted to determine what specific learning behavior strategies they’d report using, and to learn how the business model or other organizational factors of private equity supported or hindered learning from experience. Rehman found that, placing the private equity internal investment four-step model as an overlay onto the Kolb learning cycle model, there were similarities in how private equity professionals analyzed their clients’ investments (Rehman, 2020).

One of the research findings revealed that, when the participants were asked to think of an example of a time when they learned from an experience at work, 66 percent of them identified an investment disappointment, while 33 percent cited a complex transition as a key experiential learning event (Rehman, 2020).

These results aligned with all four of Kolb’s stages. The first stage, concrete experience, was shown in their daily work in the office. The second stage, reflecting on experience, was shown in the ways the participants discussed their investments after the fact with contacts, and sometimes even wrote about them. The participants also reported that they conceptualized the lessons from their investments that aligned with the third stage of Kolb’s model, abstract conceptualization. Finally, the participants stated they had applied the learning-from-experience lessons to subsequent investments, which mirrors the model’s fourth stage, active experimentation.

This tool can be useful to assess your own learning from experience. Be sure to verify that you have moved through all steps in the cycle rather than just getting stuck in the first phase (concrete experiences). Kolb suggested that failure to complete the learning cycle can lead to a failure to assimilate your learning from the experience, resulting in the repetition of poor strategies or in assumption-based solutions.

THINKING PRACTICES

Many executives have already learned the value of conducting critical reflection to assess their past thinking patterns and actions. During the interviews, the executives discussed past events and provided insights on how they were able to derive meaning from complex experiences to learn how to understand ambiguous situations with better clarity.

CREATE MEANING

The executives I interviewed had the cognitive ability (the confidence and independence) to create meaning from their actions and were then able to construct knowledge from the event, to transfer the knowledge to new situations, and to seek meaning from the new situation in order to understand the previous ambiguous situation. It sounds simple and logical, but self-reflection is one of the top leadership competencies, and leadership courses are a multibillion-dollar enterprise for a reason. Not many people take the time to review their past experiences and understand them, much less assess their thinking patterns or insights and subsequently make changes to their behavior.

Here are some of the narratives from the executives I interviewed for this book as they discussed their reflective mental models, beliefs, and thinking principles while working in uncertain situations. Charlie, the renewable energy executive, stated that “everything was very ambiguous, and since I was so embedded in the world, I just assumed that I’m creating my own universe. If you have that approach to life and to your work, then of course you get very intimate with the activity and what’s going on.” It is important to understand that your worldview can keep expanding, and as you gain insights, your perspectives will also change.

Supporting the cognitive ability to seek meaning to help explore your assumptions, the information and technology executive—Karim—said the following when discussing a complex and unique hypothetical question with his counterparts: “I asked the two presenters a question, and it was evident that they didn’t have a readily available answer. One of them was already leaning toward an ‘it depends’ type of answer, until the second presenter had the guts to say, ‘I don’t know,’ and he earned my respect right there. I value this simplicity and directness.” It may be frustrating as an executive to not have or give a definitive answer in all situations, but you need to realize that a linear thinking answer to a complex issue will only give you comfort that the decision was made, and it may not provide the best decision.

Systems can be understood by looking for patterns that could describe a potential evolution of that system. To that point, Rachid, the oil and gas executive I interviewed for the book, was in a unique and strategic position within this industry; he interacted with all the oil and gas players on a global stage at both the government and corporate levels. Rachid was tasked with pursuing an energy program that provided a sustainable and profitable remit while strengthening and growing upstream exploration and the production sector. Rachid created meaning when faced with a puzzling pattern of events related to ambiguity and stated, “You have principles, you know. You have hindsight—a perspective. If there are no precedents, if you try hard enough, you will find that even if you set your imagination on whatever information you have available, you can compile imaginary precedents to provide context for the situation.”

When faced with a unique set of challenges, your memory reflects on all your learned experiences to verify whether there is a similar past situation or patterns that may help pinpoint a direction.

KNOW THYSELF

Why is the concept of self-awareness during times of uncertainty so critical? You see executives all the ti...