![]()

PART ONE

RULING HALF THE WORLD

(Beginnings–1453)

![]()

THE HOMERIC AGE

These things never happened, but are always

Sallust, Roman philosopher, 4th century CE

It is 1000 BCE and you are sitting beneath a wall made of stones only giants could have lifted. Thunder and lightning rend the night and a bitter wind scatters sparks from the fire that warms you. You shiver and wonder. Who built this wall I sit beneath? What makes the thunder? How did I learn to make this fire? To whom or what do I owe the beauty and misery of my existence? Someone sits down beside you. He is the travelling bard, and he has the answers. Through the night he will recite them in poetry that you know almost by heart.

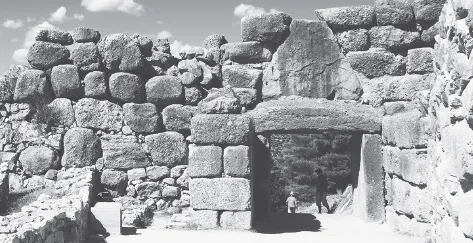

He’ll talk of Chaos that came before everything, then the first incestuous coupling that brought forth the world. How Gaia (Earth) and her son Uranus (Sky), gave birth to twelve Titans – six males and six females – plus a race of one-eyed Cyclopses and some giants, each with a hundred hands. It was they who built the wall with its huge stones.

The work of giants: Cyclopean stones at Mycenae

One of the Titans, Cronus, rebelled against his father and castrated him, then married his own sister, Rhea, by whom he had the first generation of Greek gods. But Cronus kept eating his offspring, fearing a repeat of what he’d done to his father. So Rhea spirited away her new-born Zeus, giving her husband a wrapped stone to swallow instead. Zeus came back with a potion that made Cronus vomit up the stone along with all his siblings. He banished his father and, true to tradition, took his sister Hera for wife.

Eventually, after battling it out with the Titans, Zeus and Hera came to rule over ten senior gods on Mount Olympus. There they consumed nectar and ambrosia and interfered in the affairs of mankind, not always to its benefit. It was Prometheus, a Titan not a god, who gave us fire. Zeus was so angry that he chained him to a rock, his liver to be daily pecked out by an eagle.

Next was a time of mortal heroes. Most were men and most had a god for parent. Perseus, Oedipus, Jason and Theseus battled with giants, sphinxes, gorgons and dragons to make the world safe for humans. Prometheus was eventually set free from his chains by the greatest hero of them all: Heracles.

Gorgon’s head: architectural ornament from Thassos, c.4th BCE

The Greeks looked to their gods to explain their world, to answer the questions posed by thunder and lightning, earthquake and drought. It was to them they gave thanks for the change of seasons and the glory of the heavens at night. The Milky Way (Galaxias), for example, was splashed across the nocturnal sky when Hera pulled the enormous baby Heracles from her teat. They looked to the gods, too, for answers to the questions posed by being mortal: the emotions, motives and contradictions that make us who we are. It helped that these gods were as imperfect as those they ruled over. They too loved, schemed, lusted, envied and took their revenge. Their moral instruction was limited and practical. Give hospitality (xenia) to the stranger who knocks at your door, they said, since he might just be Zeus in disguise.

The great German scholar of Greek mythology, Walter Burkert, described myth as a ‘traditional tale with a secondary, practical reference to something of collective importance’. The gods helped the Greeks to understand not just their world, but themselves. ‘Know thyself,’ prescribed the Oracle. It was the first step towards self-government.

From Myth to History

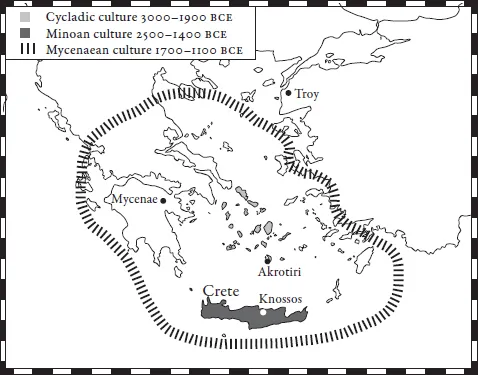

The Greek Bronze Age (3000–1000 BCE) saw three extraordinary civilisations: Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean. It was the Minoan that gave Europe her founding myth. It told of a Phoenician princess, Europa, who was gathering flowers when the ever-randy Zeus, on this occasion disguised as a beautiful white bull, carried her off to Greece to seduce her. She became the first queen of Crete and mother of King Minos, from whom the words Minoan and Minotaur are derived. Zeus so loved her that he painted himself among the stars in the shape of a bull – Taurus.

The historical Minoan civilisation of Crete (2500–1400 BCE) seems to have been a peaceful trading culture. Figurines show a caste of powerful, snake-wielding female priests, who are generally larger than their darker-skinned male counterparts. Exquisite frescoes from the Minoan settlement of Akrotiri on Santorini suggest a sea-faring civilisation given to fishing, celebration and commerce.

The Akrotiri Monkeys

How far afield did the Minoans trade? The picture is still changing. Frescoes found at Akrotiri depict monkeys with ‘s’-shaped tails that look very similar to the grey langurs of the Indus Valley. At the time when the Minoans were exporting luxury goods, like the purple dye made from Murex sea snails farmed off Crete, the rich Bronze Age Harappan Civilisation was thriving on the banks of the Indus. Is it possible that some Minoan merchant took a cargo of snails to the east, and came back with monkeys?

Minoan monkey tails: wall fresco from Akrotiri, c.17th BCE

The Mycenaean civilisation was very different. It began around 1700 BCE when the Achaeans, an eastern steppe people, migrated south and settled in the Peloponnese, the claw attached to the bottom of Greece by a skinny wrist of land they named the isthmus. Their society was hierarchical, with a warrior elite devoted to horses, and they built fortified settlements, the most famous of which were at Mycenae and Tiryns. The giant stones they used gave the name Cyclopean to this style of architecture, since later Greeks imagined only giants could have lifted them. At some point, the Mycenaeans took to the sea and came into contact with the Minoans, who introduced them to the advantages of trade.

Around 1600 BCE, the Minoan civilisation was fatally damaged by a huge eruption on the island of Thera (today’s Santorini), which buried Akrotiri’s monkeys under ash. The Mycenaean Empire, though, continued to flourish, reaching its apogee in the 12th century BCE, by which time it had spawned settlements across the Aegean, right up to the shores of Asia Minor. ‘Like ants or frogs around a pond,’ Plato would write almost a millennium later.

The Shipwreck and the Script

In the summer of 1982, a young sponge diver from the village of Yalikavak, near Bodrum in Turkey, chanced upon one of history’s most spectacular shipwrecks. Mehmed Çakır discovered the remains of a 14th-century BCE vessel that had probably sunk on its way from a port in the Levant to a Mycenaean palace in Greece. It was carrying a cargo of luxury items ranging from African hippopotamus teeth to jewellery from Canaan. The Greek Peloponnese was at the heart of a trading network that connected the great civilisations of Egypt and Mesopotamia – and possibly India, if the tails of the Akrotiri monkeys do not deceive.

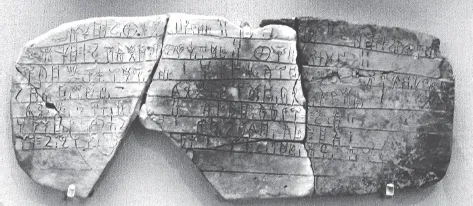

Also found in the shipwreck was a small boxwood writing tablet engraved with the mysterious Linear B script. Its deciphering in 1952 is attributed to the British architect Michael Ventris, but much of the legwork was done by Alice Kober, an academic from New York. In the 1930s, Kober began work on samples that had been found fire-baked into tablets in palaces throughout the Peloponnese. Having mastered Hittite, Akkadian, Old Irish, Tocharian, Sumerian, Old Persian, Basque and Chinese, she assembled a database in 40 notebooks on 180,000 cards, using cigarette cards when paper was rationed during the war.1 After her death her work was used by Ventris who, with the addition of some inspired guesswork, deciphered the script in 1952 and established it as Mycenaean Greek.

The signs and ideograms of Linear B were used mainly to record the distribution of goods like wool and grain to customers. They bear witness to a talent for organised trade that perhaps reached as far as India.

This Linear B tablet was baked, and thus preserved, by the fire that destroyed the Palace of Pylos, c.1200 BCE.

Iliad and Odyssey

Homer’s epics are vital staging posts on the Greek journey from myth into history. The two poems are set towards the end of the Greek Bronze Age, when the Mycenaeans might well have crossed paths with the mighty Hittite Empire, of which the city of Troy (Ilios) may have been a western outpost. On the Aegean coast of modern Turkey, just over 100 miles from today’s Greek border, it would have made an attractive target for pillage.

The Iliad describes a few crucial weeks towards the end of the ten-year siege of Troy, when the Greeks are on the point of losing the war. Everything turns on whether the semi-divine Achilles – their one-man blitzkrieg – can be persuaded to abandon literature’s longest sulk to rejoin the fight. The target of his anger is King Agamemnon, who has dishonoured him by exercising droit de seigneur over his concubine Briseis, the spoil of a previous battle.

When Achilles finally leaves his tent, it isn’t because Agamemnon has apologised, but to avenge the death of his best friend Patroclus, who has been killed by the Trojan champion, Hector. The gods intervene decisively in the encounter, as they do throughout the tale, but their interventions are capricious and unpredictable, following the twists and turns of their own internecine squabbles on Mount Olympus. They are like superpowers using the clashes of smaller nations to fight a proxy war.

Achilles wades through oceans of blood to exact his revenge, mutilating and dishonouring Hector’s corpse in a frenzy of grief and rage. Soon afterwards, though, he is visited in his tent by Hector’s grieving father, King Priam of Troy, who begs for the return of his son’s body. Against all expectations, Achilles is moved by pity and gives Hector back.

The Odyssey is very different. More human and intimate, it tells of Odysseus’s perilous journey home from Troy to the small island of Ithaca. He survives sea monsters, whirlpools, witches and cannibals – and the wrath of the sea god, Poseidon – only to find himself in the midst of another siege, that of his wife Penelope by 108 rowdy suitors. Odysseus defeats (and kills) them all in an archery contest, winning back both wife and kingdom.

What makes these two stories so important? Millions of words have been written on this subject, but perhaps it comes down what they have to say about a single question. Who decides our fate – the gods, or us?

The first word of the Iliad in Greek is ‘wrath’ (minin) and many of the next 16,000 lines seem to be part of a vast hymn to rage. Yet the whole story hinges on the moment when rage dissolves into grief and pity, as Achilles allows Priam to remove his son’s body and give him a proper burial. This is the moment when Achilles puts divinity behind him and embraces the business of being human, which is the business of grief and pity. At the start of the poem, he is more god than human, son of the sea goddess Thetis. By the end, he is the very mortal son of his mortal father, Peleus, and able to feel another father’s grief. The age of gods is over, and the age of man can begin.

In the Odyssey, composed later, humans are firmly at centre stage. Events are driven by the dangerous adventures that thwart the hero’s longed-for home-coming. It reflects a time when the Greeks were founding new homes across the known world, when it felt vital to define what it meant to be Greek.

Whether the two poems were authored by a man called Homer or emerged from a collective folk tradition, their form was more or less fixed in the sixth century BCE. They were recited again and again at festivals and other public events, including over consecutive nights at the Olympic games. Together they speak of the Greeks’ first steps towards taking responsibility for their world. They underpin later Greek political thinking, playing a...