![]()

1 |

Introduction

DAVID LOWENTHAL |

The study of landscape involves a paradox. Landscape is all-embracing – it includes virtually everything around us – and has manifest significance for everyone. Most scholarly disciplines and practical enterprises impinge on it in one way or another. Indeed, we all make our homes, do our work, and experience life in what we term landscape. It would be difficult to imagine a topic of greater importance than our relations with the world around us, in all its natural, altered, and man-made variety.

Yet virtually nothing is known about landscape as a totality. Landscape meanings and values vary from place to place and from epoch to epoch in ways that are little understood and seldom compared; we do not even know which landscape attachments are universal and which are specific to a particular time or place. How landscapes are identified and thought about; what components and attributes are discussed and admired; what symbolic meanings and physical properties they embody; how purpose, intensity, duration, realism, novelty, or impending loss affect our landscape experience – these are questions of immense import for which we have few if any answers.

Such lacunae in our understanding of landscape reflect not only the enormous scope of the subject matter it embraces but the paucity of landscape generalists. Most of us are concerned with only a tiny fraction of its multifarious meanings and uses: we are farmers or foresters or hikers or painters, seldom all these roles together. And very few of us make landscape our central concern.

Thus although landscape is a subject of generally acknowledged importance, integrated understanding of it is almost entirely lacking. The sheer multiplicity of interests that impinge on landscape – economic, aesthetic, residential, political – suggest the magnitude of the subject but at the same time seem to preclude the development of any unified perspective.

Over the past 15 years, the Landscape Research Group (LRG) has emerged as a group uniquely representative of almost the whole range of such interests. The LRG is perhaps the only organisation devoted to the study of landscape from every conceivable point of view. Two dozen LRG symposia held over the past 15 years cover a spectrum of academic and practical topics involving all the sciences and arts, and embracing most types of environments and landscape uses.

These explorations have been exciting and beneficial, enlarging the horizons of all concerned. We felt it would now be desirable to order these interests and realms of expertise within a more coherent framework that might help us to explore the whole range of landscape concepts and uses in an interrelated fashion. To this end, the LRG convened a symposium of Meanings and Values in Landscape in England in the spring of 1984. The generosity of a benefactor enabled us to cast our net beyond our usual parameters and enlist the participation of eminent individuals both in Britain and America to produce working papers on their different ways of shaping, viewing and using landscapes. The general aims of the symposium, and of this volume, were as follows.

- (a) To review concepts about landscape that are explicit or implicit in the arts, the sciences, and among landscape practitioners and users, and to organise these concepts to see how they resemble, differ from and interrelate with one another.

- (b) To survey the range of interests and uses to which landscapes are put and examine their collaborative or conflicting nature.

- (c) To assess and categorise the values, past, present and future, ascribed to landscape.

- (d) To review the range and impact of specific actions which affect the character and use of landscape.

- (e) To pinpoint lacunae in landscape understanding where research is especially needed, to provide leads for future landscape-related research that might promote the process of synthesis, and to explore how such syntheses might be extended on an international scale.

No definitive conclusions were expected; instead we sought to point the way toward future work which might revise current perspectives. The conference and this volume summarising its results are not meant to be a summing up but a starting point, not a conclusion but the beginning of a new exploration.

![]()

2 | An ecological and evolutionary approach to landscape aesthetics GORDON H. ORIANS |

A central problem in the study of human biology is to determine the extent to which our current behaviour patterns have been moulded by our long-term evolutionary history. Identifying which human behavioural characteristics are highly modifiable as a result of experience, and which are more resistant to changes because they are more constrained by genetically-based properties of the nervous system, is an extremely difficult task. There are severe limits on the ways people can be studied, and investigators are influenced by the high level of emotions generated by implications that might be labelled ‘biological determinism’. Indeed, it is currently impossible to engage in rational discourse on many aspects of the evolution of human behaviour because a majority of people, including scientists, hold such powerful a priori opinions about them.

In this complex but important arena, the study of human responses to landscapes and plant shapes offers unusual possibilities. Because selection of places in which to live is a universal animal activity, there is a considerable body of theory and data upon which to build hypotheses specifically oriented toward human behaviour (Charnov 1976, Levins 1968, MacArthur & Pianka 1966, Orians 1980, Partridge 1978, Rosenzweig 1974, 1981). In addition, because choice of habitat exerts a powerful influence on survival and reproductive success, the behavioural mechanisms involved have been under strong selection for millennia.

In all organisms, habitat selection presumably involves emotional responses to key features of the environment. It is these features that induce the ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ feelings that lead to settling or rejection. If the strength of these responses is a key proximate factor in decisions about where to settle, then the ability of a habitat to evoke such emotional states should evolve to be positively associated with the expected survival and reproductive success of an organism in that habitat. Good habitats, as measured by the features that contribute to survival and reproductive success, should evoke strong positive responses while poorer habitats should evoke weaker or negative responses. Basic responses to habitat features are likely to be modified by the presence of other individuals of the same species, both because they provide information about choices made by previous arrivals and because those individuals modify the quality of the environment (Orians 1980). Also, responses depend on the stage in the life-cycle of an organism, that is what particular resources are of greatest value to it at the moment.

For species other than Homo sapiens, these emotional states are currently unknown to us. We can observe only changes in individuals in response to alterations in the intrinsic quality of available habitats and densities of individuals in them. Human emotional responses, however, are directly accessible through verbal communication and the written word. In addition, the great capacity of people to change environments provides a source of information not available for the studies of other species that effect relatively minor alterations to their surroundings.

In this chapter I first present an overview of current thinking about habitat selection and, secondly, explore the implications of this body of knowledge for human responses to landscapes and plant shapes. Thirdly, I suggest ways of testing these ideas and review the tests that have already been made. Finally, I relate these ideas to more general notions about the evolution of a sense of beauty among people.

Habitat selection theory

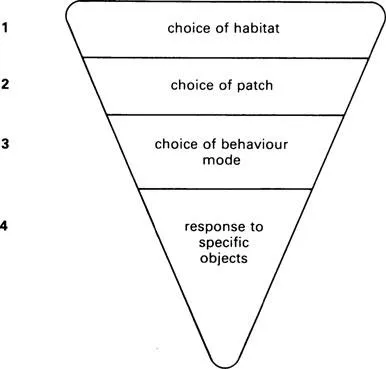

Organisms choose places in which to perform activities for a variety of reasons and their decisions affect the locations of their activities for varying lengths of time. It is convenient to view the process of selecting sites in a hierarchical framework (Charnov & Orians 1973). The number of levels identified is arbitrary, but it is useful to recognise four of them, corresponding to choice of (a) habitat, (b) patch, (c) behavioural mode, and (d) responses to specific objects (Fig. 2.1).

In this scheme, a habitat is considered to be a collection of environmental patches large enough such that the organism in question can carry out a significant part of its life cycle within that piece of terrain. For a migratory bird, a habitat would be an area in which it could complete breeding activity during the summer or, in the tropics, an area large enough to meet its survival needs for the winter. For an insect living inside a leaf and finding sufficient food inside that leaf to grow from the egg to the pupal state, the single leaf constitutes its habitat.

A patch is a piece of terrain that is internally homogeneous and different from other types of patches in the habitat. Since no two places are absolutely identical, the notion of homogeneity is a relative one. Decisions about which units to recognise as patches must be made on the basis of knowledge about the organism being studied and how it uses the environment.

Within a patch, an organism may carry out any of a large number of activities, such as feeding, defending space, courting, bodily maintenance, hiding, sleeping and nesting. Usually a single activity dominates the attention of an individual at any moment in time because most of these activities are mutually exclusive. Each activity requires a ...