eBook - ePub

Photovoltaism, Agriculture and Ecology

From Agrivoltaism to Ecovoltaism

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Photovoltaism, Agriculture and Ecology

From Agrivoltaism to Ecovoltaism

About this book

One of the challenges of our modern society is to successfully reconcile growing energy demand, demographic and food pressure and ecological and environmental urgency.

This book offers an update on a rapidly evolving subject, that of modern photovoltaic systems capable of combining the needs of energy and ecological transition. Although photovoltaic solar energy is a well-proven technical solution in terms of energy, its development can compete with agricultural land or natural sites.

New solutions are emerging: the installation of photovoltaic parks on industrial wasteland; agrivoltaics, which reconcile agricultural activity and energy production on the same surface; and ecovoltaics, which make it possible to make use of the unused surfaces under solar panels by developing ecological solutions capable of providing services to nature. These innovations are part of the response to the need to preserve terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, halt the decline in animal and plant biodiversity and participate in the development of a new mode of sustainable development and green economy.

This book offers an update on a rapidly evolving subject, that of modern photovoltaic systems capable of combining the needs of energy and ecological transition. Although photovoltaic solar energy is a well-proven technical solution in terms of energy, its development can compete with agricultural land or natural sites.

New solutions are emerging: the installation of photovoltaic parks on industrial wasteland; agrivoltaics, which reconcile agricultural activity and energy production on the same surface; and ecovoltaics, which make it possible to make use of the unused surfaces under solar panels by developing ecological solutions capable of providing services to nature. These innovations are part of the response to the need to preserve terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, halt the decline in animal and plant biodiversity and participate in the development of a new mode of sustainable development and green economy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Photovoltaism, Agriculture and Ecology by Claude Grison,Lucie Cases,Martine Hossaert-McKey,Mailys Le Moigne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Photovoltaics: Concepts and Challenges

1.1. Brief description of the different photovoltaic cell technologies

Edmond Becquerel (Figure 1.1) was a French physicist who discovered the voltaic effect. He was the son of the physicist Antoine Becquerel and the father of Henri Becquerel, who discovered radioactivity with Pierre and Marie Curie. Edmond Becquerel demonstrated for the first time that certain materials could produce small amounts of electricity when exposed to light. A photovoltaic cell is composed of two silicon-based semiconductor layers.

Figure 1.1. Photograph of Edmond Becquerel by Nadar

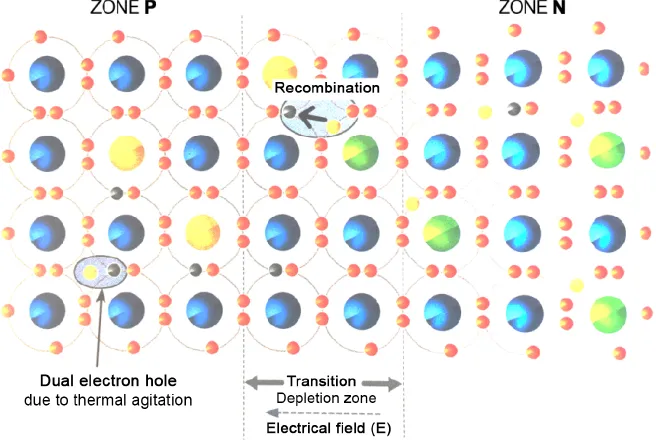

The first layer is made of silicon, which is enriched by traces of phosphorus. The phosphorus atom has one more external electron than the silicon atom. This fifth additional electron can thus circulate easily between the atoms of Si (in blue) and P (in orange). A semiconductor material known as being of type N is thus formed (negative charges in excess) (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Photovoltaic effect

(source: Moine (2016)). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/grison/ecology.zip

The second layer is made of silicon doped with traces of boron (or aluminum, in green). This time, boron (or aluminum) has one external electron less than silicon. The global atomic network thus has some electronic gaps, assimilated with a positive charge. A material known as type P is thus formed (positive charges in excess).

Following the shock of photons from the sunlight, the excess electrons (N layer) enter the P zone. This movement of electrons creates an electric field. By connecting the two layers with an electric circuit, the current can circulate (Figure 1.2). Thus, under the effect of solar radiation, the energy of the photons is transmitted to the electrons, which then transform it into electric energy.

The semiconductor materials are generally silicon and cadmium telluride. The first type is the most used. Silicon can be amorphous, semi-crystalline or crystalline depending on its mode of preparation, giving different color tones to the photovoltaic cells. The photovoltaic cells are then, respectively, gray, blue or blue and dotted with patterns left by the crystals. The structure of the semiconductor directly affects the performance of the voltaic cell and ultimately that of its assembly in solar panels. A comparative summary of the main technologies is presented in Table 1.1.

In France, the government finances up to 43% of the research and development of photovoltaic panels. Numerous studies are carried out to improve the yield of solar panels, using increasingly efficient technologies. This is one of the major challenges that academic research is currently facing in the field of photovoltaic energy. To achieve this, many efforts are being made in the production of new semiconductor materials, new cells and modules.

ADEME (Agence de la transition écologique, French Environment and Energy Management Agency) has defined several areas of research that are priorities in the strategic roadmap of photovoltaic solar energy in order to achieve the objectives set by the legislation. These areas of development for the photovoltaic industry are:

- – technology/innovation/industry;

- – building integration;

- – services and network optimization;

- – interdisciplinary themes.

The last area reflects the desire to develop a sector that generates an acceptable environmental footprint. This is a key issue, which reminds us that new technologies must be developed taking into account life cycle analysis. For example, high-performance CIGS1 technology requires the use of cadmium sulfide. Cadmium is a highly toxic metallic element, regulated by REACH (Registration, Evaluation and Authorization of Chemicals). Research is underway to replace cadmium with less toxic compounds (Zn, Mg, O, S) or indium sulfide (a rare metal).

Table 1.1. Different technologies of photovoltaic cells

| Technology | Description | Performance | Maturity |

| Amorphous silicon cell | The amorphous silicon photovoltaic cell is composed of a thin layer of silicon, much thinner than the monocrystalline or polycrystalline silicon cells. | 7% | With poor performance, it is rather intended for solar watches, garden lighting and solar calculators |

| Monocrystalline silicon cell (1st generation photovoltaics) | This is the historical sector of photovoltaics. Monocrystalline cells are the first generation of solar cells. They are made from a block of silicon crystallized in a single piece. | 16–20% | 35% of the global market |

| Polycrystalline silicon cell (1st generation photovoltaics) | Polycrystalline cells are made from a block of silicon composed of multiple crystals. They are often found in domestic, agricultural and industrial installations. | Approximately 15% | 55% of the global market (best value for money) |

| Thin layers (2nd generation photovoltaics) | The cells are composed of layers of semiconductor and photosensitive materials on a support made of glass, plastic, steel, etc. Different materials can be used, the most common being amorphous silicon. | 5–15% | 10% of the global market Decrease in production cost |

| Organic cells (2nd generation photovoltaics) | The use of polymeric materials aims to replace mineral materials with organic semiconductors, that is, plastics, for the manufacture of photovoltaic cells. These are cheap, have good absorption properties, are easy to deposit and are much lighter than the 1st and 2nd generation materials. | 20–30% | In demonstration |

| Concentration cell (CPV technology) | This technology uses optical lenses that focus light onto small, high-performance photovoltaic cells. It is necessary to always be positioned facing the sun (mobile system). | 5–10% | Experimental stage |

| Cadmium telluride cells | The manufacturing process hermetically seals a single cadmium telluride absorption layer between two glass supports. | ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword by Yvon Le Maho

- Foreword by Thomas Lesueur

- Introduction

- 1 Photovoltaics: Concepts and Challenges

- 2 Photovoltaic Energy Production and Agricultural Activity: Agrivoltaics

- 3 Innovative Principle of Ecovoltaics

- Appendices

- Appendix 1 Secondary Metabolites and Defense Molecules of Eagle Fern

- Appendix 2 Secondary Metabolites and Defense Molecules of Alder Buckthorn

- Appendix 3 Secondary Metabolites and Defense Molecules of Rhubarb

- References

- Index

- End User License Agreement