- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Throughout his work, the philosopher Theodor W. Adorno repeatedly invokes the rhinoceros. Taking its cue from one of these passages in Aesthetic Theory, 'So a rhinoceros, the mute animal, seems to say: I am a rhinoceros', this book explores the life of this animal in Adorno's texts, and articulates the nuanced interconnections between art, nature and critique in his thought.

By thus illuminating key elements of Adorno's work, this volume reveals the invaluable contributions that this 'classical' thinker can make to our current reflections on the various pressing natural and political crises of our times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adorno's Rhinoceros by Antonia Hofstätter, Daniel Steuer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Aesthetics in Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Enigma of the Rhinoceros

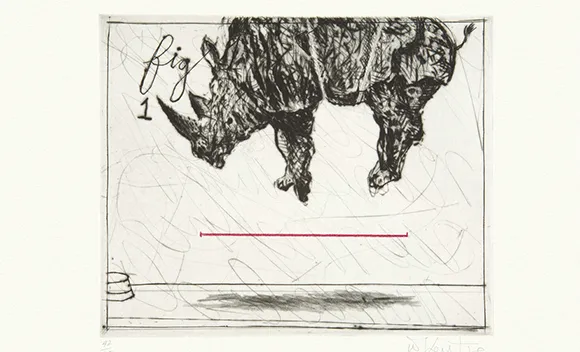

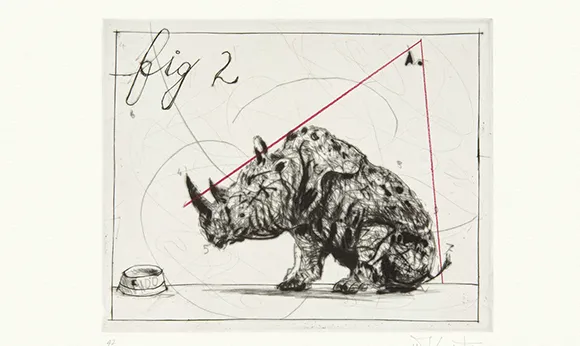

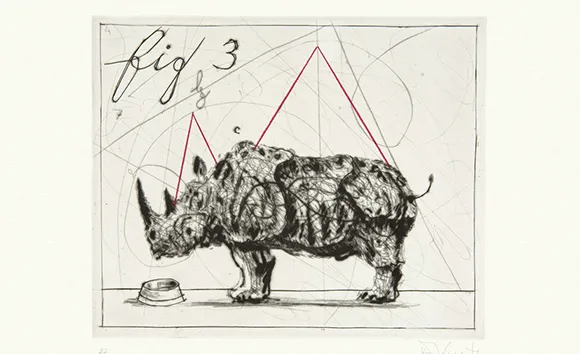

FIGURE 1 Sketches for Three Rhinos, 2005. 1. Crowd Pleaser, 2. Dunce, 3. Untitled. © William Kentridge © William Kentridge

Meeting the Rhinoceros

In the cultural history of the world, the rhinoceros has long been a source of fascination. Countless texts and artefacts, from Dürer to Dali, from Longhi to Ionesco, or, more recently, the work of William Kentridge, testify to the persistent spell that this curious creature casts over our imagination. Fascinating to us are never phenomena that we know all too well or that we do not know at all; rather, what captures our attention and elicits our curiosity is that which appears familiar but which nevertheless seems to escape our grasp, or, in reverse, that which seems unlike everything else and yet has the power to intimately move us. In short, we are fascinated by what inhabits the liminal zone of the enigmatic.

While the enigma that pertains to all that exists, as Adorno reminds us in Aesthetic Theory, is mostly forgotten – thanks to ‘the categorical net’ that people have ‘[spun] around what is other than subjective spirit’1 – the rhinoceros seems to evoke the zone of the enigmatic the moment it captures an attentive gaze. Its physical appearance marks it as curiously ‘other’, as an awe-inspiring and almost mythical creature. Grey and heavy, yet surprisingly agile under its lined and wrinkled skin, the rhinoceros is a strong and powerful animal. Embodied by its commanding appearance seems an ancient prerogative to resist domestication, a sense that is underlined by the two sharp horns that crown its bulky head. Yet the peculiarity of these horns lends this appearance of the undomesticated a further twist of strangeness, giving credibility to the anecdotes which tell of rhinoceroses that were mistaken for unicorns or dragons.2 Two shapely and surprisingly elegant ears – they almost remind one of petals or calyxes, if it were not for the dainty rim of spiky hair – and a soft and velvety mouth imbue its unusual figure with a peaceful and melancholic expression. The strange and curious appearance of the rhinoceros seems to mark it as a wondrous remnant of different times and different places. Indeed, this powerful and tender creature appears to rightly belong to a period when mammoths and dinosaurs were still roaming this planet.3 If it were not for the catastrophic fact of its near extinction, the rhinoceros would perhaps inspire the hope, which Adorno expresses in an aphorism in Minima Moralia (which will concern us later in more detail), that because it pre-existed the rise of human civilization it might also outlive its decline. Indeed, the mesmerizing effect of the rhinoceros might be owed to the perceived distance that it puts between human history and the animal itself. For Adorno, sitting by his desk in Frankfurt am Main, the rhinoceros certainly must have appeared, in the vocabulary of his time, ‘exotic’: as importing a glow of otherness, of what is untamed, into urban central Europe.4 The rhinoceros’s enigmatic semblance of otherness promises a transcendence of the here and now, of the tightly woven nexus of the ever same. Evoking that which escapes, it unsettles the seemingly all too familiar.

The recent history of the rhinoceros is of course intricately linked with that of colonialism. The exoticism that served for thinkers and artists as a reminder of what is undomesticated in the midst of ‘civilization’ is inextricable from and, indeed, reinforces the gruesome history of domination and exploitation that lies at its heart (a point that, as we will see, was not lost on Adorno). This tells us that a lot more is at stake when one is touched by the enigma of the rhinoceros. Indeed, its history is but one more proof that our fascination with animals, or with the ‘exotic’, or the ‘other’, can take the form of love and rage. These responses testify to an affinity that exists, however hidden or ignored, between human beings and animals; indeed, they draw the rhinoceros, seemingly distant in time and space, into the bounds of intimate closeness. The affinity points towards the Achilles heel of civilization: towards our shared participation in the realm of nature and, thus, ultimately, towards our own mortality. Mesmerizing and enigmatic about the rhinoceros is thus its uncanny resemblance to human beings. In a famous passage in ‘Why Look at Animals?’ John Berger seems to capture precisely this when he speaks about the gaze of animals: ‘The eyes of an animal when they consider a man are attentive and wary. […] Other animals are held by the look. Man becomes aware of himself returning the look.’5 The liminal zone of distance and closeness, familiarity and unfamiliarity, that the rhinoceros might evoke anticipates a possible reconciliation between humans and animals, nature and culture, past and present. Yet it recalls also the comprehensive domination of nature and the suffering to which it subjects all that exists.

Today, the rhinoceros has become a symbol of mass extinction: of finitude. The thought that this creature might outlive human civilization has given way to the sad insight that human civilization has already nearly achieved the total extinction of the rhinoceros. No amount of thought and no amount of hope can get around this fact. It calls, more than ever, for rigorous reflection on the relationship between humans and animals or nature and civilization.

Theodor W. Adorno was certainly one of those fascinated by this enigmatic animal. In unexpected yet crucial places in his work, a rhinoceros makes an appearance. In Aesthetic Theory – in the passage that inspires this book – it steps on to the page in the context of a discussion of the language character of works of art, a central concept of Adorno’s aesthetics. Describing the resemblance to speech of the Etruscan vases exhibited in the Villa Giulia in Rome, Adorno writes that their resemblance ‘depends most likely on their Here I am or This is what I am, a selfhood not first excised by identificatory thought from the interdependence of being’. He continues: ‘Thus the rhinoceros, that mute animal, seems to say: I am a rhinoceros’ (AT, 112, trans. modified). On the pages of Aesthetic Theory, the seeming declaration of selfhood by the rhinoceros becomes a metaphor for the seeming being-in-itself of artworks – an apparent selfhood that they mutely express but do not proclaim. In this, as Camilla Flodin lucidly elaborates in her contribution to this book, works of art imitate the expressiveness of nature and of creatures of nature: artworks mimic what Adorno also refers to as the enigmatic ‘more’ of natural beauty.

Inasmuch as artworks – and Aesthetic Theory’s rhinoceros – are imbued with the semblance of an in-itself, they anticipate the end of the domination of nature: they silently promise that the current state of universal alienation, in which the mastery of inner and outer nature has turned into the comprehensive exploitation and subjugation of nature, will not have the last word. It is here that the rhinoceros in Aesthetic Theory meets with the rhinoceros that Adorno lets loose on the pages of Minima Moralia: ‘In existing without any purpose recognizable to human beings’, Adorno writes in an aphorism entitled ‘Toy shop’, ‘animals hold out, as if for expression, their own names, utterly impossible to exchange. This makes them so beloved of children, their contemplation so blissful. I am a rhinoceros, signifies the shape of the rhinoceros.’6 Both the rhinoceros and the artwork, it is implied, point towards a world beyond universal exchangeability and anticipate a state in which subject and object are reconciled. Mass extinction, the irretrievable loss of what is unique, is its dystopian antithesis.

Rhinoceroses and artworks are enigmatic, as Adorno suggests, but what is also enigmatic is what exactly ‘the rhinoceros’ is doing in Adorno’s texts. There is a not quite accurate version of an anecdote about a dispute between Russell and Wittgenstein over the question of whether one could say with certainty that there is not a rhinoceros in the room. The anecdote is amusing because an encounter with a living rhinoceros can leave no room for uncertainty.7 And it is with such rhino-esque certainty that ‘the rhinoceros’ makes its entry in Aesthetic Theory. Its confidence is emphasized by the conjunction ‘thus’, in the sense of: ‘in this way’: ‘Thus the rhinoceros, that mute animal, seems to say: I am a rhinoceros.’ The apparent selfhood of artworks is akin to the apparent selfhood of rhinoceroses. Is that not obvious?8

The only thing that is obvious, however, is that nothing is obvious in Aesthetic Theory. It is not obvious that artworks can be compared to rhinoceroses, nor indeed that ‘the rhinoceros’ can or should show what is peculiar to artworks. And granted that one could plausibly liken artworks to animals, it is far from obvious why, at this point, ‘the rhinoceros’ is given preference over, say, ‘the elephant’. Yet unsettling certainties is part and parcel of Adorno’s critical writing strategy. Adorno, whose texts are meticulously composed in order to correctively lend voice to what is non-identical to their concepts, left little to chance when it came to his own writing. Of course, Adorno was not immune to language getting the better of him, to it storming away upon his approach as a rhinoceros might do when accidentally startled. But still, I read this passage not only as living off a play of hidden resemblances but also as engaging in a conscious and decisively critical play of form. Akin to the gesture of the ‘Here I am’, which, as Alexander García Düttmann notes in his essay in this volume, ‘seems to point to itself as a gesture’, ‘the rhinoceros’ in the text silently exposes the text as text – as something that is crafted and never fully identical to itself. When ‘thus’ ‘the rhinoceros’ makes its surprising and confident entrance, it does so as a caesura: as a gesture that interrupts and dissolves the self-certainty of thought. In an article on Adorno’s animals and the semblance of happiness, Britta Scholze puts it well when she writes that ‘Adorno’s animals emphasize the ambition of an undomesticated thinking: […] they act as irritating insertions in which a context beyond thought resonates. Adorno not only demands, as one of his famous phrases has it, a remembrance of nature in the subject; his texts also practise it through their form.’9 A text that performs the remembrance of nature in the subject is a text whose power is manifest in its own disempowerment, a kind of writing that subverts its semblance of identity in an attempt to lend voice to what exceeds its grasp.

Zoological Musings

Given the diverse vantage points of today’s global readership, which brings to Adorno’s work a wide range of contemporary expectations and sensitivities, it is necessary to stress the importance of bearing in mind the specific situatedness of Adorno’s thought not only within the intellectual and artistic context of the Franco-German tradition but also within the specific cultural constellations of the German bourgeoisie of the early twentieth century. Adorno’s thinking proceeds always in intimate engagement with these spheres – immersing itself either with generously loving attentiveness or with equally generous acidity in their texts and artefacts – in order to test and potentially transcend their bounds by means of critical reflection. Recognizing the productive and critical potential of the role of animals in Adorno’s work thus requires a familiarity not only with the commitments of his critical theory of society but also with the sociocultural parameters that it seeks to transcend. And these ‘parameters’, as we shall see, are often intimately entwined with Adorno’s own horizon of experience.10

While we might regard the use of animal metaphors in Adorno’s texts as an expression of his ‘undomesticated thinking’, it is curious to note that the animals in Adorno’s writings are almost always domesticated. Even the wild boar of his reflections on his childhood in Amorbach is granted ferocity only within the confines of a folkloristic anecdote.11 And the armoured rhinoceros in Negative Dialectics probably has more in common with Dürer’s famous woodcut and the descriptions in Brehms Tierleben – a nineteenth-century encyclopaedia of animal life that belonged to the basic inventory of the German bourgeois home and was a valued companion of Adorno’s in child- and adulthood – than with a rhinoceros that roams around the plains of Africa or Asia.12 The likeness between artworks and animals that the rhinoceros passage in Aesthetic Theory proposes therefore immediately suggests a similar parallel: just as artworks may be encountered in museums, and music in concert halls, a rhinoceros might be seen in a zoo or in the pages of a nineteenth-century encyclopaedia. Indeed, intertwined with the lines of Adorno’s dense philosophical writings are the traces of animals that appear to have been the rather tame and friendly companions of his sheltered childhood around 1900. This impression is heightened by the fact that the animals one encounters in his texts are often characters from German fairy tales, which Adorno would have read as a child and which reappear, for instance, in the titles of some of the aphorisms in Minima Moralia – such as ‘Frog King’ or ‘Wolf as Grandmother’ – or in his monograph on Mahler, where he likens a musical gesture in the Third Symphony to the way in which ‘a fearful child identifies with the tiniest goat in the clock case that escapes the bi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: The Enigma of the Rhinoceros

- 2 In the Name of the Rhinoceros: Expression beyond Human Intention

- 3 The Rhinoceros at the Bottom of the Sea: Adorno, Dürer and the Silent Eloquence of Artworks

- 4 Just One Line: Reading T. W. Adorno on Humans, Artworks, and Animals

- 5 The Mute Animal

- 6 The Speaking Animal: On a Metaphor of Humanity

- 7 The Gaze of the Rhinoceros and the ‘It’ of Aesthetic Theory

- 8 The Muted Animal

- 9 Epilogue: On the Actuality of Adorno’s Rhinoceros – Extraction, Extinction, and Dignity

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- Imprint