- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

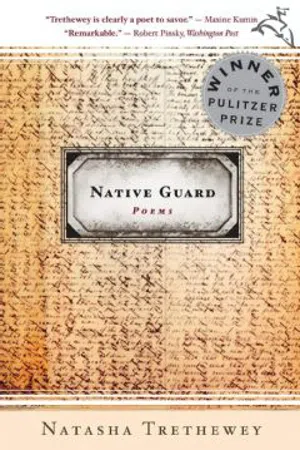

Winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry

Former U.S. Poet Laureate, Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard is a deeply personal volume that brings together two legacies of the Deep South.

Through elegaic verse that honors her mother and tells of her own fraught childhood, Natasha Trethewey confronts the racial legacy of her native Deep South—--where one of the first black regiments, The Louisiana Native Guards, was called into service during the Civil War.

The title of the collection refers to the black regiment whose role in the Civil War has been largely overlooked by history. As a child in Gulfport, Mississippi, in the 1960s, Trethewey could gaze across the water to the fort on Ship Island where Confederate captives once were guarded by black soldiers serving the Union cause.

The racial legacy of the South touched Trethewey’s life on a much more immediate level, too. Many of the poems in Native Guard pay loving tribute to her mother, whose marriage to a white man was illegal in her native Mississippi in the 1960s. Years after her mother’s tragic death, Trethewey reclaims her memory, just as she reclaims the voices of the black soldiers whose service has been all but forgotten.

Trethewey's resonant and beguiling collection is a haunting conversation between personal experience and national history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Native Guard

If this war is to be forgotten, I ask in the name of all

things sacred what shall men remember?—FREDERICK DOUGLASS

November 1862

Truth be told, I do not want to forget

anything of my former life: the landscape’s

song of bondage—dirge in the river’s throat

where it churns into the Gulf, wind in trees

choked with vines. I thought to carry with me

want of freedom though I had been freed,

remembrance not constant recollection.

Yes: I was born a slave, at harvest time,

in the Parish of Ascension; I’ve reached

thirty-three with history of one younger

inscribed upon my back. I now use ink

to keep record, a closed book, not the lure

of memory—flawed, changeful—that dulls the lash

for the master, sharpens it for the slave.

December 1862

For the slave, having a master sharpens

the bend into work, the way the sergeant

moves us now to perfect battalion drill,

dress parade. Still, we’re called supply units—

not infantry—and so we dig trenches,

haul burdens for the army no less heavy

than before. I heard the colonel call it

nigger work. Half rations make our work

familiar still. We take those things we need

from the Confederates’ abandoned homes:

salt, sugar, even this journal, near full

with someone else’s words, overlapped now,

crosshatched beneath mine. On every page,

his story intersecting with my own.

January 1863

O how history intersects—my own

berth upon a ship called the Northern Star

and I’m delivered into a new life,

Fort Massachusetts: a great irony—

both path and destination of freedom

I’d not dared to travel. Here, now, I walk

ankle-deep in sand, fly-bitten, nearly

smothered by heat, and yet I can look out

upon the Gulf and see the surf breaking,

tossing the ships, the great gunboats bobbing

on the water. And are we not the same,

slaves in the hands of the master, destiny?

—night sky red with the promise of fortune,

dawn pink as new flesh: healing, unfettered.

January 1863

Today, dawn red as warning. Unfettered

supplies, stacked on the beach at our landing,

washed away in the storm that rose too fast,

caught us unprepared. Later, as we worked,

I joined in the low singing someone raised

to pace us, and felt a bond in labor

I had not known. It was then a dark man

removed his shirt, revealed the scars, crosshatched

like the lines in this journal, on his back.

It was he who remarked at how the ropes

cracked like whips on the sand, made us take note

of the wild dance of a tent loosed by wind.

We watched and learned. Like any shrewd master,

we know now to tie down what we will keep.

February 1863

We know it is our duty now to keep

white men as prisoners—rebel soldiers,

would-be masters. We’re all bondsmen here, each

to the other. Freedom has gotten them

captivity. For us, a conscription

we have chosen—jailors to those who still

would have us slaves. They are cautious, dreading

the sight of us. Some neither read nor write,

are laid too low and have few words to send

but those I give them. Still, they are wary

of a negro writing, taking down letters.

X binds them to the page—a mute symbol

like the cross on a grave. I suspect they fear

I’ll listen, put something else down in ink.

March 1863

I listen, put down in ink what I know

they labor to say between silences

too big for words: worry for beloveds—

My Dearest, how are you getting along—

what has become of their small plots of land—

did you harvest enough food to put by?

They long for the comfort of former lives—

I see you as you were, waving goodbye.

Some send photographs—a likeness in case

the body can’t return. Others dictate

harsh facts of this war: The hot air carries

the stench of limbs, rotten in the bone pit.

Flies swarm—a black cloud. We hunger, grow weak.

When men die, we eat their share of hardtack.

April 1863

When men die, we eat their share of hardtack

trying not to recall their hollow sockets,

the worm-stitch of their cheeks. Today we buried

the last of our dead from Pascagoula,

and those who died retreating to our ship—

white sailors in blue firing upon us

as if we were the enemy. I’d thought

the fighting over, then watched a man fall

beside me, knees-first as in prayer, then

another, his arms outstretched as if borne

upon the cross. Smoke that rose from each gun

seemed a soul departing. The Colonel said:

an ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Theories of Time and Space

- I

- The Southern Crescent

- Genus Narcissus

- Graveyard Blues

- What The Body Can Say

- Photograph: Ice Storm, 1971

- What Is Evidence

- Letter

- After Your Death

- Myth

- At Dusk

- II

- Pilgrimage

- Scenes from a Documentary History of Mississippi

- Native Guard

- Again, the Fields

- III

- Pastoral

- Miscegenation

- My Mother Dreams Another Country

- Southern History

- Blond

- Southern Gothic

- Incident

- Providence

- Monument

- Elegy For The Native Guards

- South

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- About The Author

- Connect with HMH

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app