- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

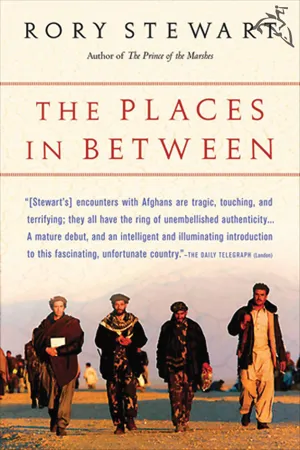

The Places In Between

About this book

The

New York Times bestselling account of a thirty-six-day walk across Afghanistan, shortly after the fall of the Taliban: "stupendous . . . an instant travel classic" (

Entertainment Weekly).

In January 2002, Rory Stewart walked across Afghanistan, surviving by his wits, the kindness of strangers, and his knowledge of Persian dialects and Muslim customs. By day he passed through mountains covered in nine feet of snow, hamlets burned and emptied by the Taliban, and communities thriving amid the remains of medieval civilizations. By night he slept on villagers' floors, shared their meals, and listened to their stories of the recent and ancient past.

Along the way Stewart met heroes and rogues, tribal elders and teenage soldiers, Taliban commanders and foreign-aid workers. He was also adopted by an unexpected companion—a retired fighting mastiff he named Babur in honor of Afghanistan's first Mughal emperor, in whose footsteps the pair was following.

Through these encounters—by turns touching, confounding, surprising, and funny—Stewart makes tangible the forces of tradition, ideology, and allegiance that shape life in this beautiful, beleaguered country.

In January 2002, Rory Stewart walked across Afghanistan, surviving by his wits, the kindness of strangers, and his knowledge of Persian dialects and Muslim customs. By day he passed through mountains covered in nine feet of snow, hamlets burned and emptied by the Taliban, and communities thriving amid the remains of medieval civilizations. By night he slept on villagers' floors, shared their meals, and listened to their stories of the recent and ancient past.

Along the way Stewart met heroes and rogues, tribal elders and teenage soldiers, Taliban commanders and foreign-aid workers. He was also adopted by an unexpected companion—a retired fighting mastiff he named Babur in honor of Afghanistan's first Mughal emperor, in whose footsteps the pair was following.

Through these encounters—by turns touching, confounding, surprising, and funny—Stewart makes tangible the forces of tradition, ideology, and allegiance that shape life in this beautiful, beleaguered country.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Herat . . . The policeman at the cross-roads with a whistling fit to scare the Chicago underworld—Robert Byron, The Road to Oxiana, 1933Herat . . . The police directing a thin trickle of automobiles with whistles and ill-tempered gestures like referees—Eric Newby, A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush, 1952Herat . . . A small lonely policeman in the center of a vast deserted square, directing two donkeys and a bicycle with a majesty and ferocity more appropriate to the Champs Elysées—Peter Levi, The Light Garden of the Angel King, 1970

![[Image]](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/3184087/images/ThePlacesInBetween-3-plgo-compressed.webp)

Chicago and Paris

On my last morning in Herat, I was reluctant to get out of bed. It was cold despite my Nepali sleeping bag, and I knew it would be colder in the mountains ahead. I put on my walking clothes: a long shalwar kemis shirt, baggy trousers, and a Chitrali cap, with a brown patu blanket wrapped around my shoulders. I went into the dining room for breakfast. Foreigners were forbidden to stay in any hotel other than the Mowafaq—perhaps, I now thought, to make it easier for the Security Service to monitor us. War reporters had occupied most of the tables in the previous week, and I had spent a lot of time with them. I noticed that Matt McAllester and Moises Saman, whom I liked, had not yet appeared. They had been drinking Turkmen champagne the night before in the UN bar to celebrate Moises’s birthday.

Television France 2 had brought their own cafetière and a packet of Lavazza coffee and sent to the bazaar for fresh juice. The day before, I had heard them talking about Chinese motifs on a shrine, the similarity between the minarets and factory chimneys, and the soldiers that chased them from the Bala Hissar fort. Now they were discussing whether to visit the handblown-glass shop or the refugee camp. One of them was pointing out the window at the traffic policeman. These things had attracted the attention of foreigners in Herat for seventy years. I had read five different travel writers on the traffic policemen. Their peaked hats and whistles struck visitors as particularly incongruous among the tumult of the Afghan bazaar. I wanted to write about them myself.

I sat beside Alex, the Telegraph correspondent, whom I had met in Jakarta, and Vaughan Smith, who had been a Grenadier Guards’

officer before he became a freelance cameraman. He had been filming in Afghanistan for a decade.

“Are you leaving this morning?” asked Vaughan.

“I hope so.”

“And you are really going to walk to Kabul through Ghor?”

“Yes.”

Vaughan smiled. “Good luck,” he said, and gave me his fried eggs. I ate six eggs to stock up on protein. Then I took up my stick and pack, said good-bye, and walked into the street. A strong, cold wind was blowing the sand into the air and I had to squint.

On the street corner, I watched men unloading tablecloths from China and Iranian flip-flops marked “Nike by Ralph Lauren.” From Tabriz a truck had brought the goods through a fog of diesel fumes down the multilane highway that the Iranian government still called the Silk Road. This was the route that Alexander the Great took in pursuit of a Persian rival. The Persian had fled up the central route into the mountains, and Alexander, instead of following him, had taken the safer Kandahar route to Kabul. I watched a fruit wrapper from Isfahan flying in Alexander’s footsteps. I followed the Persian, and came upon a man with a prosthetic leg, whom I had met before.

![[Image]](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/3184087/images/ThePlacesInBetween-1-plgo-compressed.webp)

“Shoma Ghor miravid?” (Are you going to the province of Ghor?) he shouted.

“Yes.”

“Shoma be ghabr miravid” (You are going to your grave), he replied. I shook his hand and walked on as he repeated the pun “Ghor miyayid . . . ghabr miyayid” and laughed.

Huma

When I reached his office, Yuzufi stood, smiled, fastened his double-breasted jacket very slowly, and came round his large desk to embrace me. As I sat down, a dozen people barged through the door. I recognized them from the hotel—Wall Street Journal, Guardian, Deutsche Allgemeine Zjeitung—but none of them acknowledged me. Young Kabuli translators in pleated leather jackets and baggy trousers formed their train. As they approached Yuzufi’s desk, they spoke over the top of each other in English: “Can we see him?” “Can we make an appointment to see him?” “But His Excellency said . . . ,” “There is no higher authority,” “With no letter?” “What happens if?” And as though it were a comic opera, Yuzufi’s deep bass voice broke in, in harmony: “It is not known . . . Worry not . . . All will be fine . . .”

The journalists were demanding access to a Taliban prisoner. Yuzufi was promising to look into it. This overture had been rehearsed many times. Some of the journalists had been in town for a fortnight without getting inside the jail. Now, confronted by Yuzufi’s patient obfuscation, they snapped at their translators who, being far from Kabul, were almost as confused as the journalists. Finally, Yuzufi still talking, they all wheeled around and flowed out without saying good-bye, leaving only me and the row of peasants by the door.

Yuzufi smiled. He was meant to be searching for the letters of introduction I had acquired with trouble in Kabul. I waited for him to say that he had found them. He didn’t. Instead, he said, “I was thinking about you last night, Rory. You are like a medieval walking dervish.”

He compared me to Attar, who lived in the twelfth century under the dynasty of Ghor. When Genghis Khan invaded, Attar was killed for making a joke, and Rumi, whom Attar had held as a baby, walked to Turkey to found the whirling dervishes.

“What you will see on your walk,” he continued, “is that we are one country today just as we were in the twelfth century under the Ghorids, in Attar’s day.”

I smiled. Whereas the new governor was learning the jargon of a postmodern state, Yuzufi had an older view of an Afghanistan with a single national identity, natural frontiers, and ambassadors and a culture defined by medieval poetry. The Security Service saw my walk only as a journey to the edge of Ismail Khan’s terrain. The Hazara area was as foreign to them as Iran. But for Yuzufi my walk was a journey across a united country. Perhaps this was why he was one of the only people who thought the walk possible.

“I,” Yuzufi sighed, “would love to come with you, but I am like the birds that refused to join the sacred quest.” Then he quoted some poetry that may have been Attar’s description of the birds’ excuses for staying at home:

The owl loves its nest in the ruins,

The Huma revels in making kings,

The falcon will not leave the King’s hand,

And the wagtail pleads weakness.2

Finally a soldier marched in and, holding his right hand to his chest, said, “Salaam aleikum. Chetor hastid? Jan-e-shoma jur ast? Khub hastid? Sahat-e-shoma khub ast? Be khair hastid? Jur hastid? Khane kheirat ast? Zjnde bashi.”

Which in Dari, the Afghan dialect of Persian, means, “Peace be

with you. How are you? Is your soul healthy? Are you well? Are you well? Are you healthy? Are you fine? Is your household flourishing? Long life to you.” Or: “Hello.”

He was a small man in his mid-forties with bandy legs, a wispy chestnut brown beard, and pinched purple cheeks. In a webbing pouch he carried a military radio, his link to headquarters; a pen, suggesting he was literate; a packet of pills, showing he could afford antibiotics; and a roll of pink toilet paper, a more subtle status indicator.

Yuzufi did not stand up to greet him, but he moved three files on his heavy wooden desk and replied with his nine greetings. Against the far wall of the office, four Afghan villagers sat uncomfortably straight on plastic chairs, their rubber galoshes planted squarely on the linoleum. Beneath frayed shalwar pajama trousers, their narrow brown ankles were covered with white hairline cracks and scars. They had been waiting for hours to speak to Yuzufi.

“I am Seyyed Qasim,” continued the soldier, emphasizing the title Seyyed, meaning descendant of the Prophet, “from the Department for Intelligence and Security.”

“Indeed. Seyyed Qasim, I am His Excellency Yuzufi,” Yuzufi, who was also a seyyed, replied. “This is His Excellency Rory, our only tourist, standing by, ready for you to walk with him.”

My escort did not glance in my direction.

“Salaam aleikum,” I said.

“Waleikum a-salaam,” the small man replied. He turned back to Yuzufi. “Well, Your Excellency, we have a Land Cruiser outside.”

“Please understand,” I interrupted, “I am walking to Chaghcharan.”

“To Chaghcharan? No.” Seyyed Qasim stood straight and made firm statements, but he did not seem comfortable in this office. He kept looking around the room. His eyes were small and blue, his eyelids puffy.

“Not just to Chaghcharan,” said Yuzufi, “to Kabul.”

“He will be killed. What is this foreigner trying to do?”

“I am a professor of history,” I said.

Qasim squinted at my shabby clothes and frowned.

The door swung open and a younger soldier marched in and saluted. He was about six feet tall—nearly seven inches taller than Qasim—and much broader than Qasim in the shoulders. Unusually for an Afghan who came from a rural area, he had shaved his beard, leaving a drooping mustache that made him look like a Mexican bandit. Visible in his webbing were five spare magazines, three grenades, a packet of cigarettes, and again a bundle of pink toilet paper. Qasim introduced him as Abdul Haq.

Yuzufi, who had been skimming two files, now looked up and spoke to them at length. Turning to me he added, “I have told these two that you have met His Excellency the Emir, Ismail Khan, and that he wished you luck on your journey. They are to do what you instruct and you will record their bad behavior. Your walk starts now.” He stood up from behind his desk and gravely enfolded my hand. “Record me in your book. As the Persian poet says: ‘Man’s life is brief and transitory, Literature endures forever.’”

He smiled. “Good luck, Marco Polo.”

Fare Forward

We walked down the corridor and pushed through the crowds still waiting to present petitions to the governor. When we reached the street, rather than turning west to the hotel, we turned east toward the desert and the mountains. The sun had come out, casting a harsh clear light over the sand-caked brick and sharpening the shadows of tired men pushing handcarts. As we walked, I adjusted the straps of my pack and wondered what I had forgotten to buy and would therefore have to do without for the next two months. I felt the familiar unevenness in the inner sole of my left boot, stretched my toes, and paced out. My companions were carrying only automatic rifles and sleeping bags, and had no food or warm clothing.

I felt a little ludicrous in my Afghan clothes, shrugging my shoulders under the weight of the pack. Qasim, the older man, was wearing neatly pressed camouflage trousers made for someone much larger. He had gathered the loose waist in pleats beneath his belt, but the thigh pockets reached his midcalf. Although he was the senior man, Qasim seemed much less comfortable than Abdul Haq. He kept his red, pockmarked face down, his eyes flickering nervously as though he were waiting for something to erupt from the pavement. Abdul Haq had an upright stance and looked very tall beside Qasim. He took two paces for every three of Qasim’s.

Nobody on the street even glanced at us and neither Qasim nor Abdul Haq looked at me. They didn’t speak English. I guessed that they had only an uncertain idea of the walk ahead, that they had not dealt with a foreigner before, and that they were relatively junior. Since their uniforms looked as though they had just been unpacked from an American consignment, I also assumed they were new to their jobs. But they handled their weapons comfortably. We walked side by side, or almost, for the street was crowded an...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Epigraph

- The New Civil Service

- Tanks into Sticks

- Whether on the Shores of Asia

- Part One

- Chicago and Paris

- Huma

- Fare Forward

- These Boots

- Part Two

- Qasim

- Impersonal Pronoun

- A Tajik Village

- The Emir of the West

- Caravanserai, Whose Portals . . .

- To a Blind Man’s Eye

- Genealogies

- Lest He Returning Chide . . .

- Crown Jewels

- Bread and Water

- The Fighting Man Shall

- A Nothing Man

- Part Three

- Highland Buildings

- The Missionary Dance

- Mirrored Cat’s-Eye Shades

- Marrying a Muslim

- War Dog

- Commandant Haji (Moalem) Mohsin Khan of Kamenj

- Cousins

- Part Four

- The Minaret of Jam

- Traces in the Ground

- Between Jam and Chaghcharan

- Dawn Prayers

- Little Lord

- Frogs

- The Windy Place

- Part Five

- Name Navigation

- The Greeting of Strangers

- Leaves on the Ceiling

- Flames

- Zia of Katlish

- The Sacred Guest

- The Cave of Zarin

- Devotions

- The Defiles of the Valley

- Part Six

- The Intermediate Stages of Death

- Winged Footprints

- Blair and the Koran

- Salt Ground and Spikenard

- Pale Circles in Walls

- @afghangov.org

- While the Notes Lasts

- Part Seven

- Footprints on the Ceiling

- I Am the Zoom

- Karaman

- Khalili’s Troops

- And I Have Mine

- The Scheme of Generation

- The Source of the Kabul River

- Taliban

- Toes

- Marble

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Footnotes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Places In Between by Rory Stewart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.