- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

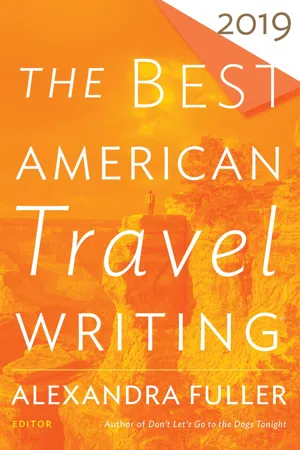

The Best American Travel Writing 2019

About this book

An eclectic compendium of the best travel writing essays published in 2018, collected by Alexandra Fuller. BEST AMERICAN TRAVEL WRITING gathers together a satisfyingly varied medley of perspectives, all exploring what it means to travel somewhere new. For the past two decades, readers have come to recognize this annual volume as the gold standard for excellence in travel writing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Best American Travel Writing 2019 by Jason Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN

The End of the Line

from Smithsonian

And men will not understand us . . . and the war will be forgotten.—Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front (1928)

One Sunday morning in the 11th Arrondissement of Paris, lured by hydrangeas, roses, and pigeons, I strolled past a playground filled with children’s voices. The cool white Parisian sky made me want to sit on a bench and do nothing. Behind the playground a church bell tolled the hour, a crow told time in its own voice, and a breeze suddenly hissed through the maples.

It was a hundred years since the First World War had come to an end. Earlier that morning, approaching Paris by taxi, I passed an exit sign for the Marne, reminding me that in one of the many emergencies of that war thousands of soldiers were rushed from Paris by taxi to fight the First Battle of the Marne. Now a couple sat down on the bench next to me and began kissing. Who is to say that what they were doing wasn’t a better use of their time than studying and carefully remembering war? And how then shall I recommend the Great War to you? Let me try: its hideous set pieces retain their power to balefully dazzle us right through the earthen darkness of a hundred years! Let its symbol be the 198-pound German Minenwerfer, which a Canadian eyewitness described as follows: “At night it has a tail of fire like a rocket. It kills by concussion.”

This essay, my attempt at remembrance, is, like any of our efforts, peculiar, accidental, and limited. I should have visited Berlin, London, Vienna, Flanders, the city formerly known as Brest-Litovsk, and the various territories of the warring colonial empires. (For instance, the 295,000 Australians who fought, and the 46,000 who died, will be barely mentioned here.) I would also have liked to see my own country as it was in 1918.

Instead, to see where the conclusive fighting was done, I went to France to find what battle graves I could: the Marne, the Somme, the Meuse-Argonne, Verdun, the St. Quentin Canal. The “fountains of mud and iron,” in Remarque’s phrase, had run dry; what about the hatreds and memories?

Beginnings, Raptures, Robberies

You might think Europe and its 40 million finally dead or wounded were dragged into the muck by a series of insults and bumbling miscommunications, a whole continent at the mercy of foolhardy monarchs and military strategists who, “goaded by their relentless timetables,” as Barbara Tuchman relates in The Guns of August, “were pounding the table for the signal to move lest their opponents gain an hour’s head start.” Not so, according to many participants. “The struggle of the year 1914 was not forced on the masses—no, by the living God—it was desired by the whole people.” Thus the recollection of a young Austrian soldier named Adolf Hitler, who enlisted with a Bavarian infantry regiment as quickly as he could, and served almost to the end. “Overpowered by stormy enthusiasm, I fell down on my knees and thanked Heaven from an overflowing heart for granting me the good fortune of being permitted to live at such a time.” Could the war truly have been desired? That sounds as fatuous as the grinning death’s-head emblem on a German A7V tank. But a German historian who despised the Führer likewise remembered the “exaltation of spirit experienced during the August days of 1914.” For him, the war was one “of defense and self-protection.”

Like Hitler, the aspiring British poet Robert Graves joined the colors almost immediately. He enlisted to delay going to Oxford (“which I dreaded”), because Germany’s defiance of Belgian neutrality incensed him, and because he had a German middle name and German relatives, which caused him to be suspected. Other Britons were as enthusiastic as Hitler. “Anticipation of carnage was delightful to something like ninety percent of the population,” observed Bertrand Russell, the Nobel Prize–winning philosopher. Trotsky, witnessing the jubilation in Vienna, remarked that for “the people whose lives, day in and day out, pass in a monotony of hopelessness,” the “alarm of mobilization breaks into their lives like a promise.”

One might equally well blame diplomatic incompetence, Austro-Hungarian hubris, or the partially accidental multiplier effect of a certain assassination in Sarajevo. And then there was Kaiser Wilhelm, with his mercurial insecurities, military fetish, and withered arm—to what extent was he the cause? In a photograph taken New Year’s Day 1913, we see him on parade, beaming in outright exultation and taking clear kindred pleasure in wearing a British admiral’s uniform. (He was, after all, the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria.) Twelve years after the armistice, the British military theoretician Liddell Hart, who was shelled and gassed as a young infantry officer at the front, made the case against the kaiser bluntly: “By the distrust and alarm which his bellicose utterances and attitude created everywhere he filled Europe with gunpowder.”

The historian John Keegan, in his classic account The First World War, called it “a tragic, unnecessary conflict.” If that fails to satisfy you, let me quote Gary Sheffield, a revisionist: “A tragic conflict, but it was neither futile nor meaningless,” his idea being that liberal democracy in Europe depended on it. Meanwhile, in came the Russian autocracy and Turkish sultanate to complement the empires of Germany and Austria-Hungary; however necessary they thought the war, by entering it they utterly erased themselves.

Some war tourists may be disposed to amble along a more fatalistic line, so here it is: three years before the slaughter, a certain General Friedrich von Bernhardi explained the birds and the bees in Germany and the Next War: “Without war, inferior or decaying races would easily choke the growth of healthy, budding elements, and a universal decadence would follow.”

Reader, have you ever read more inspiring words to live by?

The Static

1

A certain influential treatise entitled Weapons and Tactics, published in 1943 by the British military historian and man of letters Tom Wintringham and updated 30 years later, divides military history into alternating armored and unarmored periods. The Great War was something in between. Those glorious unarmored days when a sufficiently frenetic cavalry or bayonet charge could break through enemy lines still dazzled the generals. Yet the “defensive power” of machine guns, of barbed wire, and of the spade (for digging) “had ended mobility in war.” Meanwhile, the future belonged to tanks: “a brood of slug-shaped monsters, purring, or roaring and panting, and even emitting flames as they slid or pivoted over the ground.”

Underestimating this armoring trend, German strategists prepared to follow the “Schlieffen Plan,” named for Alfred von Schlieffen, chief of Germany’s Imperial General Staff from 1891 to 1905, who conceived a rapid flank attack around French firepower. It had to be rapid, in order to defeat France and swing round against Russia before the latter completed mobilization. Well, why not?

To strike France according to timetable, one had to set aside the trifling matter of Belgium’s neutrality. But who dreaded their armor, their dog-pulled machine guns? So the Germans put on their knee-high, red-brown leather jackboots and, in the first days of August 1914, marched on Belgium.

The First Battle of the Marne began in early September. At this point the opposing armies still enjoyed some freedom of movement. The tale runs thus: an over-rapid advance (à la Schlieffen) of an already disequilibrated German Army beyond its line of supply was answered by French troops—some of whom, as you already know, were frantically delivered to the front by Parisian cabs—and a strong attack on the German right flank led finally to a so-called “failure of nerve,” which caused the Germans to retreat to the Aisne River. Here they settled into trenches until 1918.

As one General Heinz Guderian put it: “The positions ultimately evolved into wired, dug-in machine-gun nests which were secured by outposts and communication trenches.” Take note of this German, if you would. He was young enough and flexible enough to learn from his defeats. We will meet him again and again.

2

Upon his arrival at the front, Robert Graves’s commander explained that trenches were temporary inconveniences. “Now we work here all the time, not only for safety but for health,” Graves writes. How healthy do you suppose they were, for men sleeping in slime, fighting lice and rats, wearing their boots for a week straight? The parapet of one trench was “built up with ammunition-boxes and corpses.” Others, Graves wrote, “stank with a gas-blood-lyddite-latrine smell.” From an Englishman at Gallipoli: “The flies entered the trenches at night and lined them with a density which was like moving cloth.”

Let the little village of Vauquois, 15 miles from Verdun, represent the trenches. The Germans took it on September 4, 1914. In March of the following year, the French regained the southern half, so the Germans dug in at the hillcrest and in the cemetery. In September 1918 the Americans finally cleared the place. During those three static years, a mere 25 feet separated the battle lines in Vauquois—surely close enough for the adversaries to hear each other.

Ascending a short steep path through thick forest, where strands of ivy ran up verdant trees approaching the white sky with its sprinkle of rain, I found on the summit near an unimpressive monument the ruins of Vauquois’s town hall, which were forbidden to the public by means of red-and-white-striped tape. Twisted rusted relics of agricultural equipment lay on display in a kind of sandbox. Here one could look down over a checkerboard of forest and field to faraway Montfaucon, one of the enemy strongpoints that General John J. Pershing’s “doughboys” would face in the great Meuse-Argonne Offensive of 1918. And just below me lay a great crater in the grass, its depth maybe 100 feet or more, where at one point the Germans had detonated 60 tons of subterranean explosives, killing 108 French infantrymen in an instant.

I descended into no-man’s-land, passing the hole where the church used to be, then up into the German positions where a steel-faced hole, almost filled in, grinned below the grass. Ahead rose more forest—none of it old growth, of course, for by 1915 Vauquois and its trees had been improved into mucky craters. The fact that everything was now overgrown I had thought to be a blessing, but taking a step into the greenness I encountered waist-high tangles of barbed wire or dangerous bunker holes whose lips for all I knew might collapse beneath me.

To pulverize positions at so near a distance, a soldier was well served by the so-called trench mortar, which fired its projectile almost straight up, so that it would come down with great force upon one’s neighbors. And just here I found a trench mortar excavated from its concrete-and-steel-lined pit. Like most of the ordnance still remaining on the Western Front, it wore a black finish—the work, said the local historian Sylvestre Bresson, who was my battlefield guide for a part of my travels, of postwar preservationists, for during its working career it would have sported field-gray paint. The thing came up to my navel. Its barrel was more than large enough for me to put both arms in.

I proceeded farther into the German lines, whose lineaments were mostly disguised by dandelions, daisies, goldenrod, nettles, and other weeds. The humid coolness was pleasant. How could I even hope to envision the reputed 10 miles of burrows on this side? One of the trenches wound conveniently before me, between belly- and chest-high, its concrete softened by moss, and its next turning celebrated by a rusty bracket—maybe the rung of a ladder.

I clambered down into its clamminess. I followed a dandelion-crowned mossy, winding trench whose side tunnels went darkly down. Here gaped a square pit like a chimney with double-braided strands of rusty barbed wire at ankle height in the creepers just beyond. I drew prudently back. A collector might have liked that German barbed wire, which was thicker than the French version. (Bresson told me that French-issued cutters of the period could not break it.) With its long alternating spikes it looked more primitive and more vegetally “organic” than the barbed wire of today. How many French assaulters with twisted and bloody ankles had it held up long enough for the defenders to machine-gun them?

Returning to the path, I found more dark, filthy, stone-faced and metal-faced dugouts. Stooping down to peer into a mucky tunnel, I braced my hands upon a perimeter of sandbags whose canvas had rotted, the concrete remaining in the shape of each bag.

Every known World War I veteran has died; the very notion of “remembering” the war felt problematic. How could I even imagine the hellish noise? What about the smells? A Frenchman left this description: “Shells disinter the bodies, then reinter them, chop them to pieces, play with them as a cat does a mouse.”

3

By the close of 1914, with the war less than half a year old, the Western Front stretched static, thick, and deep for 450 miles. The Eastern Front took on a similar if less definitive character, finally hardening between Romania and the Baltic in 1915. In a photo from November 1915 we see a line of German soldiers in greatcoats and flat-topped caps shoveling muck out of a winding narrow trench, grave-deep, somewhere in the Argonne Forest. The surface is nothing but wire, rock, sticks, and dirt.

The generals thought to break the stasis using massive concentrations of artillery. Somehow, surely, the enemy positions could be pulverized, allowing charges to succeed? Weapons and Tactics: “Most of the history of the War of 1914–18 is the history of the failure of this idea.”

You see, artillery barrages, to say the least, called attention to themselves. The enemy then thickened its defenses where needed. Furthermore, the shelling tore up no-man’s-land, so that assault parties, instead of rushing forward, floundered in shell holes, while the enemy shot them down. In one typical outcome, Graves’s comrades “were stopped by machine-gun fire before they had got through our own entanglements.”

However perilous it was to “go over the top,” the defensive positions were themselves hardly safe. Graves writes time and time again about witnessing the deaths of his comrades right there in the earthworks. He feared rifle bullets more than shells, because they “gave no warning.” On the opposite side of the front, Hitler emoted: “In these months I felt for the first time the whole malice of Destiny which kept me at the front in a position where every n—— might accidentally shoot me to bits.”

And so their various armored immobilities stalemated the belligerents. The British were losing as many as 5,000 soldiers a week in what they called “normal wastage.” Unable to go forward, unwilling to retreat, the adversaries tried to speed up normal wastage. That is why, as early as the fall of 1915, the French and British decided on a quota of 200,000 Germans killed or wounded per month.

“Thus it went on year after year; but the romance of battle had been replaced by horror.” That was Hitler again. He, of course, remained “calm and determined.”

4

The German assault at Verdun announced itself on February 21, 1916, with the detonation of more than a thousand cannons. Something like 33 German munitions trains rolled in each day. In a photo of a second-line casualty station, we see a wounded Frenchman sitting crookedly on his crude stretcher, which rests in the dark mud. His boots are black with filth; likewise his coat up to his waist and beyond. A white bandage goes bonnet-like around his head, the top of it dark with blood. His slender, grubby hands are part folded across his waist. His head is leaning, his eyes almost closed.

In a bunker near Verdun 100 years later I came upon a chamber whose rusty ladder ascended to a cone outlined with light, which silhouetted something like a giant mantis’s desiccated corpse: the under chassis of a machine gun. Nearby ran another emplacement that Sylvestre Bresson thought must be part of the Maginot Line, thanks to its newer concrete. (I should remind the reader that this latter imposing bulwark was intended, decades later, to use all of World War I’s advantages of entrenched defense against that World War II aggressor, Hitler. For why wouldn’t war haunt this same ground over and over again?)

A Russian offensive against the Austrians in the east, followed by a French attack at the Somme in July, finally forced the Germans to disengage from Verdun. In October the French retook its most massive fort. The battle, the longest of World War I, finally ended on December 15. Then what? Mud, corpses, duckboards, trenches, broken trees. French and German casualties each exceeded 300,000 men.

But why disparage all this mutual effort? If its object was to kill multitudes of human beings, let’s call it a triumph, as evidenced by the French National Necropolis at Fleury-devant-Douaumont. Driving down the hill, we came upon 15,000 white crosses flashing in the sun. I went out to wander those tombstones on the down-slanting grass where crimson-petaled rose beds ran along each row. Up at the chapel, French soldiers in uniform stood gazing down across the stones, the occasion being a change of commander. “For us this is the most sacred site,” Bresson remarked. “If France could keep only one memorial to World War I, it would be this one.”

These 15,000 dead men were all French, but nearly 10 times the amount of remains, both French and German, broken and commingled, lay in the nearby ossuary. Looking in through the many ground-level windows, I saw heaps of bones and skulls in the darkness. Some yellow-brown fragments had been combined into almost decorative columns, as in the Paris catacombs.

In the edifice above them stood a Catholic chapel with stained-glass windows, and in a glass c...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Introduction: Travel in the Time of Awakening

- STEPHEN BENZ: Overlooking Guantánamo

- MADDY CROWELL: The Great Divide

- DAVID FETTLING: Uncomfortable Silences: A Walk in Myanmar

- ALICE GREGORY: Finished

- MATT GROSS: How the Chile Pepper Took Over the World

- RAHAWA HAILE: I Walked from Selma to Montgomery

- PETER HESSLER: Morsi the Cat

- CAMERON HEWITT: A VISIT TO CHERNOBYL: Travel in the Postapocalypse

- BROOKE JARVIS: Paper Tiger

- SAKI KNAFO: Keepers of the Jungle

- LUCAS LOREDO: Mother Tongue

- ALEX MACGREGOR: Is This the Most Crowded Island in the World? (And Why That Question Matters)

- JEFF MACGREGOR: Taming the Lionfish

- LAUREN MARKHAM: If These Walls Could Talk

- BEN MAUK: The Floating World

- DEVON O’NEIL: Irmageddon

- NICK PAUMGARTEN: Water and the Wall

- ANNE HELEN PETERSEN: How Nashville Became One Big Bachelorette Party

- SHANNON SIMS: These Brazilians Traveled 18 Hours on a Riverboat to Vote. I Went with Them.

- NOAH SNEIDER: Cursed Fields

- WILLIAM T. VOLLMANN: The End of the Line

- JASON WILSON: “The Greatest”

- JESSICA YEN: Tributary

- JIANYING ZHA: Tourist Trap

- Contributors’ Notes

- Notable Travel Writing of 2018

- Read More from the Best American Series

- About the Editors

- Connect with HMH