![]()

I

Base Notes

Mojave

Invisible Indians

Romantic Scientist

Orientals

Beloved

![]()

Mojave—Perfume Interlude

HEAD

Black Copal

Wild White Sage

Blue Eucalyptus

Juniper Leaf

HEART

Palo Santo

Linden Blossom

Honey

BASE

Mitti Attar

Sandalwood

Leather

Norlimbanol

My path to the Native history of this land is through permaculture, the indigenous plants, the native plants, the soil, where the water runs—I am learning to read the land. In Sufi mysticism, to experience an ascent on the spiritual path, one has to feel and cycle back to a spiritual poverty, a place where there is nothing. From that place, the longing for the Divine starts. Where being starts. Where you listen. The more I get to know the desert, the emptier it becomes.

—Fariba Salma Alam,

American Bangladeshi artist, in an interview

Joshua Tree, January 2020. In the morning, I meditated, wrote by hand, and did yoga asanas in the backyard, beside the lone Joshua tree in the yard, its wayward branches casting a shadow like an arboreal Durga. I spent the rest of the day making myself simple lunches, quesadillas or pasta, comfort I craved because I knew that what I’d be reading for research would hurt. In the afternoon, I would drive to the park to take a hike and record what I saw and smelled. Juniper needles I cracked between my fingers, the scent of wet clay from the remnants of snowfall in the shadows between boulders, untouched by the sun.

I found a spot near the Oasis of Mara, and watched the sunset bathe the desert pink. I stayed until the full moonrise above the peaks that formed over two billion years ago. Darkness settled. I surrendered to silence, as stars populated the night sky. As I beheld this immense expanse, I recalled my grim morning reading, about a colonial-era famine in Bengal. Death disguised as exploration, expansion, natural selection, manifest destiny, white supremacy, industrialization, and innovation. This land, where the Mojave and Sonoran deserts meet, once belonged to the Serrano, Cahuilla, Chemehuevi, and Mojave tribes. The presence of water in a desert is a gift, and once they lived near this oasis, until white settlers descended with violence. Where I sat in a rented jeep, hemmed in by the park, had been land they’d lived on for thousands of years. Their descendants live on in Twenty-Nine Palms and Coachella, far from their ancestral oasis.

After two weeks of intense work in the desert, I noticed that my scalp had started to feel tender, that I was losing clumps of hair each day. I discovered a bald ring, just as my grandmother had first discovered my alopecia years ago, when she’d been braiding my hair. Alopecia returned whenever I felt heartbroken, usually over a person, not history. Reading these narratives produced stress in my body, triggering an autoimmune response. Research suggests trauma is recorded in our genes, but some scientists argue this is circumstantial, and that encoding trauma as something we inherit in our bodies would be undesirable. I believe in science, but I believe in the unknowable, too. I lost my hair, my sleep, my desire to eat, sick to my stomach as I’ve absorbed these stories.

Do we need scientific evidence to prove that the violence against our ancestors affects us, too?

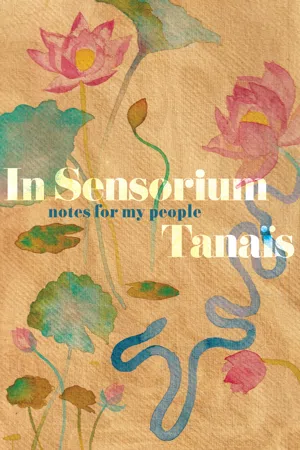

We cannot turn back time and resurrect the world before genocide. I made a perfume called Mojave, to honor the First People of this land. Sacred notes of palo santo, wild white sage, and black copal are the incenses of the Americas, burned in ceremony for protection and clarity; as oils they smell as cool as a desert night.

One morning after meditation, I tripped and dropped a crystal, a smooth white sphere of selenite that I keep on my writing desk. This reminded me of the splitting of the moon, a miracle in Islam—one that has multiple interpretations; that Muhammad is a true prophet, that the day of judgment will split believers and infidels. From Surah Al-Qamar, The Moon: the hour has come near / the moon has split in two / they see a miracle / they turn away and say / this is passing magic—I prefer my own interpretations. The moon’s dark side is unseen, but we know it’s there. The splitting of the moon, my body’s unraveling, a portent of everything to come.

![]()

Invisible Indians

Perfume as Erotics & Past Lives

NOTES

Musk & Choya Nakh

Like the snake, I am my own future.

—Natalie Diaz, “Snake-Light,” Postcolonial Love Poem

Language is a skin: I rub my language against the Other . . . my language trembles with desire—

—Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse

MEMORY

Will we be ruined? This is the first thing I wonder, when we begin our—affair—if loving without touch counts as one. What do you mean, ruin? you write back. I imagine you whispering the word, ruin, wondering how a fantasy has that sort of power. I mean a love that ruins us because we have to hide. Love doomed by repression and secrecy. Love bound by a lust insatiable as it is impossible, we are fucked, fucked over, in its aftermath. The ruins of a lover, their imprint on us—vasana—their skin, their scent, and traces fixed in our mind. Ruins of femmes you’ve loved in secret before me, the ruins of those we will hurt to have each other, the ruins of women you are bound to by duty—wife, child, mother, sister. Love as duty, burdened by the crushing weight of another’s need. I have loved Indian men before, but none ever chose me as their mate. Each time, their love became an extraction, ultimately, a rejection. I’m not sure you understand what it feels like to be from a people who are considered backwards by other people who look just like them. I suppose what I’m asking you: Will you ruin me?

My birth name sounds like the word for water in Tamil, the mother tongue that you cannot speak. Vacanai is the Tamil word for perfume, perhaps a loanword from the Sanskrit, vasana. Given how ancient Dravidian language is, and still spoken by millions today, I wonder if it’s possible that language flowed in the opposite direction, from Tamil to Sanskrit, which evolved in the second millennium BCE, entombed as the liturgical language of scripture, governance, literary arts, the realm of the so-called twice-born, men who’ve been initiated into Vedic rituals, Brahmins, like you; forbidden for women or lower-caste people, long before femmes like me converted to Islam or called themselves Dalit. Of course, they knew these rituals, because they are a part of them, mala makers stringing flower garlands, makers of incense and tilak paste and sacred fires, right there, as high-caste men chanted and performed their purification rituals. Outsider means that you are invisible until you provoke or bother the social order—then you become hypervisible—being excluded makes you keenly aware of your oppressor. As a youth, I felt enthralled by the pantheon of female deities, the pujas, the mantras, that belonged to my Indian Bengali Hindu family friends, even though I’d never be invited to take part in their prayers. Only years later, as an adult, living in India, would I partake in puja, but I suppose I was passing as a Hindu.

Vasana is a karmic memory, traces of a former life carried into the next; an imprint of a person or a place you once knew. These are the perfumes we know from other lifetimes, in the Hindu tradition a sense of cosmic déjà vu, a scent that we’ve encountered before. As with most words in Sanskrit, there are double, multiple, sometimes opposing meanings. Vasana also means a perfume enfleurage, pressing flowers into fat, so that a fragrance is transferred into a new medium. In the medieval Indian process, described in the perfumery treatise Gandhasara, the perfumer placed flowers with sesame seeds in a scented cloth. The sesame seeds were crushed, as the scent of the flowers diffused into the oil, becoming the perfumed vasana. Flowers that don’t want to express their oils easily, like jasmine or tuberose, too delicate for the stress of steam distillation, are well-suited for vasana. Thousands of flowers are steeped and replenished and steeped, until their fragrance is imprinted into the fat, like a memory. In my mother’s village dialect, bashna is a pleasant odor, whereas bashona in Bengali, or vasana in Hindi, means desire. Impressions processed in our brain’s olfactory bulb move onward to the ancient almond in our brain, the amygdala. Memory, scent, desire—an archetypal trine. Laced throughout this text are vasanas that live in my body, my own, those of my family, those of my people. They’re not precise recordings, just what I remember. When we know a person’s body, as we inhale them, our mind forms a memory, a vasana of their scent into our own body. Their molecules imprinted into our minds. Medieval Indian perfumers named the blending of wet substances vedha, piercing. We are activated by different senses, me, smell, you, sound, my voice aspirated with pleasure an erotic jolt for you, and the scent of my perfume on another person’s skin does the same for me.

You and I study each other’s faces in photographs, little art videos of me gazing and spinning and filtered and dreamy, soft smoky voice notes, voyeur to my orgasm. I don’t yet know what you smell like. I never want to be seen too close. I want to be a fantasy, I’m not at home in my body as much as I project this on the Internet, filters let me hide myself, the parts that I’m half a generation too old to love fully, the folds of my belly, the black brush of pubes, calloused feet, nipples only drawn out by teeth, useless to feed the baby that I’ll never have, the shyest part of my body. If we knew each other in a past life, did I have these same eyes that you love to gaze into through the little portal in your hand? These eyes that are near-sightless without my glasses. In another life, when I felt you inside of me, were you just a blur?

Can I be your muse? We ask this of each other, as if we needed permission to be inspired by desire. Art is where our longing must go, how this distance disappears, a sublimation of sex into text. I’m not sure you know what you’re asking, though, to be a writer’s muse is to surrender the boundary of a secret for the story. We always choose the story; I cannot be kept a secret. Men like you have always loved femmes like me. We have always been your muses, we know all the sordid details—the cheating on your wives, the brokenness, the lies—that are written out of the patramyths you tell the world. All of the great Indian epics depict low-caste women as smelly, filthy, destructive. We know too much, so you have to disassociate from us, the shamed woman, the woman who talks too much, the femme who doesn’t give a fuck. We are inherently ruinous for powerful men.

Love feels like a visit to another country, love infatuates new language, I begin making up words to describe this feeling, one that I’ve never quite had as an adult: loving an Indian man, and being loved in return. Sliding into a chat is nothing new, from my first moment online, in an AOL chatroom, I was furiously cybersexing Indian boys, who may have been pedophilic men in their thirties for all I know. Meeting Indian boys on the Internet let them lust after a girl who would likely scandalize their mothers. In the closed box of the chat, we found a safe space for filth, our little wet dreams came alive. When I got older, dates with desi guys in finance became more about scoring a fancy dinner to escape the drudgery of grad school, my diet of a pizza slice or truck burritos. Hooking up led to nowhere, I couldn’t fake the wifey shit. You remind me of the thrill of the secret of my first crushes, my first loves and heartbreaks in high school, the delicious sensation of a secret blooming inside of me. I had long given up on this sort of connection happening ever again—the Indian men I’ve loved always ended up dating or marrying professional women of their own caste or religion, their same class status, skyrocketing to wealth. Or they ended up with white women. Bangladeshi men never even considered a bad femme like me an option, their mothers never sent over biodatas—you can’t spin a respectable lover résumé out of me. The sorrow that this sentiment brings up in me is old, a wound that I want to heal with you.

Apocalypsexual, that’s my word for longing for someone at the end of the world, love in exile, eleven miles—lifetimes—apart. Our conversations are at turns dissertations and psychosexual revelations and confessions, an archive of deep secrets, intellectual, spiritual, lucid, unfiltered thoughts, we begin to name our traumas and our families’ traumas, our shame. We experience a free range of feelings with each other, knowing full well that our fantasy is a fiction that might turn true if we choose. The inexplicable part of all of this is that I’ve known you before, in a past life, a belief that I didn’t grow up with, nor am I supposed to believe. Our kink, our karma, the actions we’ve carried from one life to the next that have brought us to this erotic encounter, one that feels much older than we can understand. Do you believe in gods? I wonder, as I have reconnected to my belief in All—h, just as I begin to know you.

What does sacred mean to you? You asked me this once, and I want to answer: Everything. I sense mysticynicism in you; you are a natural skeptic, or maybe just discerning. I wonder if you’ve numbed the part of you that trusts the sacred. Do you feel deadened by the very systems designed to kill us? You want to know what I find sacred? That you make music, reach for transcendence, for you and for your listener, a gift that connects you to something vaster than sound. I consider this sacred.

Each night this week I’ve sat on the stoop with Jenny. I haven’t chain-smoked American Spirits in years, but we stay up until dawn, talking about the uprising after the murder of George Floyd, the eons of violence our people have survived, the fear we feel because we chose to be artists. One of the inheritances of colonization is what I call mysticynicism, a persistent doubt of the Unknown, the Divine, the Sacred. When I toss quarters stamped with the face of an enslaver/first president to read divinations from the I Ching, the Chinese Book of Changes, it’s not just some New Age shit, it’s ancient shit. I use the book to illuminate situations that confuse me, like you, and I can’t extricate how freely I read these words from what Jenny told me. How Chinese people and scholars were imprisoned and killed just for using the I Ching, for making art that calls truth to power. Sitting with her each night, I realize how relieved I am to be writing in a time that she is, finding the mystic and tender and traumatic in the past, as we imagine the future. I think about how she and I may have known each other in other lifetimes, too.

My entire space could fit inside your brownstone, I imagine, we’ve never been over to each other’s houses, in the old world, when there used to be house parties....