- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

An essential guide to living better for longer, Brain Power breaks down the science behind brain function and reveals why sleep, exercise, diet and even socializing are so important for our health.What does it mean to have a healthy, happy brain, and why is it so important to look after our grey matter? Comprehensive and illuminating, this is an essential and up-to-date examination of how lifestyle choices impact our ability to maintain a healthy brain.Focusing on important areas such as diet, sleep, exercise, brain training and emotions, Brain Power explains the science behind what really affects our brains, as well as providing practical tips and exercises to improve and support brain function into old age.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Brain Power by Catherine de Lange in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Self Improvement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

DIET

The brain is a hungry organ, consuming about 20 per cent of the body’s energy. And yet, when we choose what to eat, we are more likely to be thinking about the effects on our physical health. Is it good for the heart? Will it make me put on weight? Does it cause cancer or diabetes? It’s not just individuals who think this way: by and large the medical profession too has underappreciated the role that diet plays in our mental wellbeing. That is despite the fact that we have long known that the gut is not a standalone organ, and that it is in constant dialogue with the brain. Now, science is starting to home in on this conversation, and the findings are quite astounding.

One way that the gut and brain communicate is through the microbiome, on which there has been an explosion of research in recent years. In Chapter 1, we get acquainted with the trillions of microbes living within us, and discover the incredible ways they influence our wellbeing. Crucially, we will also learn how to feed them to keep them – and by default, ourselves – happy.

In Chapter 2, we go on to explore the idea that it isn’t just what we eat, but also when, that plays a role in staying sharp. Fasting diets of all types are growing in popularity, but are they all they are cracked up to be, and can going hungry really fine-tune your brain?

Bad diet is the leading risk factor for death in the majority of countries around the world, claiming more lives than smoking.4 Where have we gone wrong? In Chapter 3, we take a tour of some of the global hotspots that have the healthiest diets, and learn from them and the latest research about what we should actually be eating for optimal brain health and a long and healthy life.

Finally, if you still aren’t convinced about the role of diet on the brain, in Chapter 4 we turn to what happens when our body’s ability to cope with food breaks down, and to the striking idea that Alzheimer’s disease could be a kind of diabetes of the brain.

Throughout this part of the book, we will discover the antidote to the multitude of diets and fads that promise a quick fix, and instead learn the sustainable, delicious changes that we can make to our diets to keep our brains fighting fit.

CHAPTER 1

What to eat to boost your mood

Butterflies in your stomach on a first date, a gut feeling that someone isn’t being honest with you, even a tummy upset in anticipation of a big work presentation: we have all experienced the connection between the gut and the brain in some form. But did you know that the gut has its own nervous system? Or that the gut is in constant dialogue with the brain, influencing your thoughts and moods even when you aren’t eating? This connection is so strong that scientists have come to call the gut our second brain, and are gleaning a better understanding than ever of how we can all nurture this connection to feel and think better.

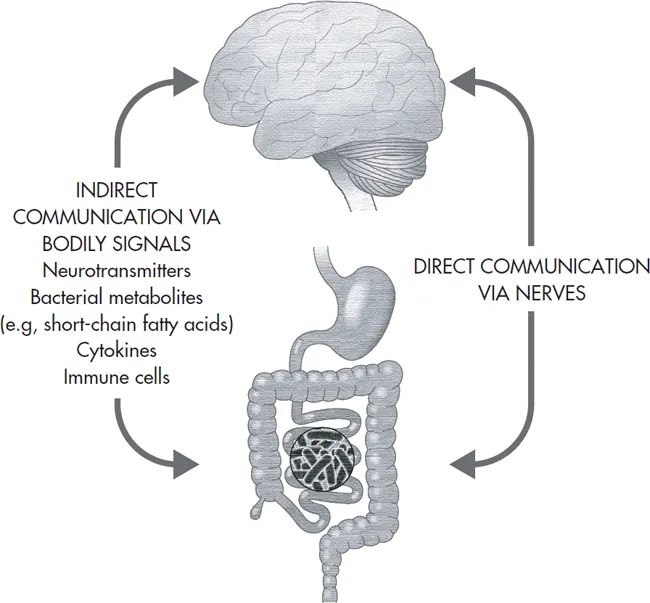

The two-way communication between the gut and the brain is called the gut–brain axis, and information can travel back and forth in a number of ways. The most direct is the vagus nerve, an information super-highway that sends signals from our gut to our central nervous system, and is a key player in the body’s ‘rest and digest’ mode. The vagus nerve is considered to be the body’s sixth sense,5 because of its ability to detect activity in our organs and communicate that important information back to the brain. Aside from the vagus nerve, the gut can talk to the brain in other ways, including through hormones, the immune system and through our gut microbes.

Our understanding of the influence of the gut–brain axis on our mental health is relatively new, especially the role of the microbes that live in our gut. Even so, it’s an extremely exciting area of research, with compelling evidence that the way we treat these residents of our intestines can have a profound influence.

Meet your microbiome

We have an estimated 40 trillion microorganisms living in our digestive tract. To put this into perspective, this is about the same number as cells that make up the human body, and there are 100,000 times more microbes in your gut than there are people on the Earth.6

They predominantly make their home in the large intestine, the final part of the digestive tract, and the slowest part of the digestive system, taking about twelve to thirty hours to process what’s coming through, giving plenty of time for our gut microbes to work their magic. These trillions of microbes, which include bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites, are together called our microbiota. In combination they house hundreds of times more genes than your own genome – all the genetic material in your own body. It is this collection of microbial genes that we call the microbiome.

Remarkably, until the twenty-first century, 80 per cent of the microbes in our guts were a mystery to us. That’s changing thanks to gene-sequencing technology, and in 2007 the Human Microbiome Project was launched to sequence our ‘second genome’. We are now entering an exciting phase, where the focus is shifting from what these inhabitants are, to what they are getting up to in there – and how we can make the most of them to influence our physical and mental health.7

We often hear talk of ‘good bacteria’, and this is a key concept when we think about our gut microbiota. Our digestive tract is one of the prime ways that harmful organisms can enter the body. If we have enough ‘good’ bacteria in there, any unwanted pathogens will be outnumbered, helping to protect us from infection. This is one reason why, when it comes to health, it’s important to have as diverse a microbiome as possible. The more skills it can perform, the more it can do to keep us well.

But our gut residents do much more than simply outcompete harmful microbes. They also break down foods that are indigestible to us, producing a number of useful compounds, or metabolites, and make vitamins, including all eight B vitamins. Remarkably, our gut microbes can also produce neurotransmitters, the chemicals our brain cells use to communicate, including serotonin (a lack of which is implicated in depression), noradrenaline (which primes the body for action) and dopamine (which plays a vital role in mood, and in our ability to learn and plan). In fact, 50 per cent of our dopamine is made in the gut.8

Powerful influencers

All of this goes to show that our gut microbes are not merely passengers hitching a ride inside us. Their health is tightly connected to our own, and they can exert a powerful influence over our brain.

Just how big that influence is has started to become clear through research over the past decade or so, starting with studies in germ-free mice. These are mice that are bred without any microbes and raised in a sterile environment, allowing scientists to see what effect exposure to various microbes has on them. Pioneering research in 2004 by a team of Japanese researchers found that these microbiome-free mice had underdeveloped brains, an exaggerated stress response, and seemed to act as though they were depressed.9 Tellingly, after the mice were fed a mix of bacteria, their stress response quickly became normal.

Further compelling evidence comes from studies using faecal transplants, during which faecal material from one individual is transferred to the gut of another, often through an enema or sometimes orally, for instance in pill form. One review of this technique, published in 2020, looked at studies of faecal transplants into mice from people with specific conditions. After the mice received the transplant, they developed symptoms similar to those seen in humans – including depression, anxiety, anorexia and alcoholism. Of course, these symptoms aren’t exactly the same as in people, but are a proxy – for instance, mice displaying anxiety will spend less time in the middle of an open field, preferring to stick to the edges. Those displaying compulsive behaviours will frantically bury marbles, given the chance. Simply transferring the microbiome of someone who is poorly into these mice seemed to also transfer the health issue.

What if we could do the opposite, and transfer the microbiome of healthy individuals into those with pre-existing health conditions, in an attempt to get rid of them? It’s a tantalizing idea, and while few studies have taken place in people, a handful do exist. For instance, the review identified six studies where feacal transplants took place from healthy volunteers to people with depression, and all of the studies found short-term improvements in depressive symptoms in those receiving the transplants. However, the symptoms generally returned to previous levels after several months.

ANTIBIOTICS AND THE MICROBIOME

On the whole, antibiotics seem to be bad news for your microbiome, messing with the balance of microbes in your gut (of course they are also an incredibly important treatment for bacterial infections, so you should still follow doctor’s orders where needed). However, the picture is complicated by evidence suggesting that activity of antibiotics on the microbiome might also help people with persistent negative symptoms of schizophrenia or those with depression who are resistant to standard treatments. So the role of antibiotics on the microbiome – in both the treatment and prevention of disease – is likely to become a hot topic in the years to come.

As for how these effects take place, it could be through any of the number of ways the gut talks to the brain. Neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids, produced when gut microbes chew up fibre from our diet that we can’t digest ourselves, can both fire up the vagus nerve, sending signals to the brain. Indeed, when mice have their vagus nerve cut, the beneficial effects of gut microbes disappear.

Short-chain fatty acids are also anti-inflammatory and can influence the immune system in other ways too. Given that many psychiatric illnesses are influenced by inflammation (see Chapter 25 for more on this), the anti-inflammatory powers of the gut microbiome are particularly intriguing.

The psychobiotic revolution

Faecal transplants are still an extreme option and in 2020 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning over the risk of serious infections related to the practice.10 An alternative suggestion is that we might give people probiotics – bacteria that have proven health benefits for the gut – as a way to treat mental-health problems, an idea that leading researchers John Cryan and Ted Dinan at University College Cork in Ireland and their colleagues coined ‘psychobiotics’.

But how sure can we be that effects of the microbiome we see in animals apply to humans? One piece of evidence starts with a tragedy in 2000 in the Canadian town of Walkerton, Ontario, when heavy rains caused the water supply to become infected with E. coli and campylobacter from cattle excrement. It resulted in an epidemic of bacterial dysentery, which infected half of the population and tragically killed seven. Many of the survivors went on to develop post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. But, says Dinan, a significant proportion of patients developed major depressive illness by the end of the first year, suggesting that the pathogen somehow managed to impact on their brains.11 Research also shows that people with depression, PTSD and schizophrenia have striking similarities in their microbiome that they do not share with matched controls.

Adding to the idea that our gut microbes influence our emotions, investigations of healthy women using brain scans have shown that the levels of certain bacteria in their guts influences the way they respond to emotional pictures – so much so that researchers could use the brain images to predict which kind of gut bacteria the women had. This was pretty convincing evidence that these gut-residents can influence our emotional responses.12

The team responsible for these findings, from the University of California, Los Angeles, went on to show that giving women a probiotic yogurt containing bacteria twice a day for four weeks improved the way their brains processed emotions. In clinical populations – that is to say, those already with a mental-health condition – probiotics might also help. In some studies, the approach has been found to reduce symptoms of depression a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Diet

- Part 2: Sleep

- Part 3: Physical Exercise

- Part 4: Mental Exercise

- Part 5: Social Life

- Part 6: Healthy Body, Healthy Mind

- Part 7: The Influence of You

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

- Acknowledgements

- Index