![]()

CHAPTER 1

EVERYDAY LIFE

The Calendar

First Invented: Scotland Date: 8000 BC

From earliest history, mankind has been fascinated by the sky and its two most prominent occupants – the sun and the moon. It was only natural that we should start to keep track of the fluctuations in these two celestial objects. The passage from day to night is one obvious interval, as is the cycle from new moon to full moon and back again. And for hunter-gatherers or early farmers, it was also crucial to understand the rotation of the seasons through the year.

Making sense of these various measures was a complex task. For instance, there is no tidy number of lunar months in a solar year. Twelve lunar months take about 354 days and you either need to find a way to add those odd days back into your system or to accept a gradual slippage in how the years relate to the seasons. And that’s before you even start to think about the problem of leap years ...

Calendars of various sorts were clearly in use before the Bronze Age. We have written records of calendar systems from the Sumerian, Egyptian and Assyrian civilizations dating to about 5,000 years ago. However, one recent archaeological find in a field in Scotland, at Craithes Castle in Aberdeenshire, suggests that calendars were in use much earlier than that.

The site contained a series of twelve pits, which seem not only to show the phases of the moon but also to monitor lunar months. The pits, which have been dated to 10,000 years ago, also align with the midwinter sunrise. This would allow the hunter-gatherers who created them to reset each year correctly to align with the seasons, which suggests significant levels of understanding and sophistication in the pre-agricultural Mesolithic people of the area. The academic Vince Gaffney, who was in charge of the scientific analysis of the site, said that it ‘illustrates one important step towards the formal construction of time and therefore history itself’.

Plato’s Water Alarm Clock

First Invented: Fourth century BC

We sometimes imagine the past as a time without clocks, when everything moved at a much gentler pace. Of course, life is not as simple as that, and there have been many historic situations in which people needed to find ways to keep to a busy schedule. For instance, the Greek philosopher Plato (427–347 BC) wanted a way to get himself and his students out of bed in time for lessons. As a result, he became the inventor of the alarm clock.

Simple water clocks – in which the gradual drip of water into or out of a vessel is used to record the passing of time – had been in existence in Babylon and Egypt by the sixteenth century BC. It is also possible that such clocks were used earlier in India and China, as long ago as 4000 BC. The innovation in Plato’s water clock was that it also featured an alarm. A vessel was gradually filled with water, until it reached the height at which a tube led out of the first vessel into a lower receptacle. The tube functioned as a siphon, meaning that as soon as water started to drain out through it, the rest of the water was sucked into the tube with it. As a result, all of the water was instantaneously dumped into the lower receptacle. This lower receptacle was almost completely enclosed, except for a few small openings designed to act as whistles when air was forced through them – which happened when the water fell. So Plato’s students were woken up, along with their teacher, by a loud whistling noise emanating from the extraordinary alarm clock.

Other early alarm clocks worked in similar ways. One involved a vessel that filled with water until it became heavy enough to fall and clatter onto a table below, making a loud noise in the process. Another design used a candle with a metal ball embedded in it, which burned down until the wax around the ball melted and fell onto a metal surface.

Beekeeping

Mesolithic rock painting of a honey hunter.

Bees are older than humans in evolutionary terms, and throughout human history we have been fascinated by the problem of how to get at their honey. A Spanish rock painting from 8,500 years ago shows men stealing from the nests of wild bees. However, the history of beekeeping, where the bees are kept in artificial hives, is a much more recent story. A temple at Abu Ghorab in Egypt, dating from the Fifth Dynasty (2500–2400 BC), shows successive stages of honey manufacture – from taking honeycomb from the hive to draining the honey into jars. It was a key ingredient of many Egyptian medicines, as well as being used in cooking. The Egyptians made hives from dried mud, while the Greeks and the Romans refined the method using clay hives. The scale of manufacture in ancient Egypt is shown by the fact that in the twelfth century BC an offering of over 30,000 jars of honey was made to appease the gods. One of the few ancient civilizations to reject the use of honey was the Spartans, who described cakes made from honey in rather macho terms as ‘no food for free men’. The more enthusiastic attitude taken by other cultures was summed up by a Roman blessing: ‘May honey drip on you.’

The Mechanical Clock

First Invented: China Date: Eighth century

Sometimes the joy of history lies in the small details, such as the original names of inventions. The world’s first mechanical clock went by the name of the ‘Waterdriven Spherical Birds’-Eye-View Map of the Heavens’.

Invented by Yi Xing, a Buddhist mathematician and monk, in AD 725, it was developed as an astronomical instrument that incidentally also worked as a clock. In spite of the name it wasn’t strictly speaking a water clock (one in which the quantity of water is used to directly measure time). However, it was water-powered – a stream of falling water drove a wheel through a full revolution in twenty-four hours. The internal mechanism was made of gold and bronze, and contained a network of wheels, hooks, pins, shafts, locks and rods. A bell chimed automatically on the hour, while a drumbeat marked each quarter-hour.

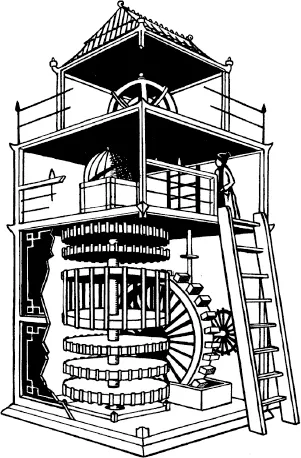

Another splendidly named clock was the ‘Cosmic Engine’ built by the Chinese inventor Su Song between AD 1086 and 1092 for an emperor of the Sung Dynasty. This was also a mechanical astronomical clock, but it was huge, spreading over several storeys in a tower that was over 10 metres (35 feet) high. It was made of bronze and powered by water. At the top, a sphere on a platform kept track of the motion of the planets. The clock remained in place and working until 1126 when it was lost in a Tatar invasion.

The Chinese engineer Su Song’s hydro-mechanical clock tower.

Mesoamerican Chocolate

First Used: Central America Date: c. 1750 BC

Today chocolate is a tasty treat enjoyed around the world, but did you know that it was once the food of gods, and that it has even been used as money? The cacao bean grows in the wild parts of Central America. The seeds grow inside a long sheath, inside of which a sweet pulp contains about thirty-five beans. They taste quite bitter, and it was possibly the sweeter pulp that people first ate or drank. However, when they were fermented, the beans could also be made into a drink. The earliest archaeological evidence of this method of consumption comes from a clay vessel, from about 1750 BC, which shows the residue of a chocolate beverage. At this stage the drink would have been bitter, as sugar wasn’t grown in the Central American region before the arrival of the Europeans.

We don’t know much about how these early chocolate drinks were prepared, but evidence from the later Mayan civilization may give us a clue about the older traditions. In a document from about the thirteenth or fourteenth century AD, cacao is identified as a sacred drink, which was associated with Kon the rain god in particular. The Mayans believed that cacao pods were made ripe by droplets of the blood of their gods. They prepared their version of the drink, which was also believed to grant virility to the men who drank it, by combining a paste made from the beans with water, cornmeal and chilli, then transferring the bitter brew from one cup to another to produce a foamy topping. (Women were traditionally banned from drinking this concoction for fear of the effect this virile drink might have on them.)

In the Aztec Empire – which ruled a large area in modern Mexico (north of the region of the Mayans) from the fourteenth century until the Spanish conquest started in the sixteenth century – cacao beans were a valuable commodity. Because the beans didn’t grow in drier weather conditions, the Aztecs started to impose taxes on their subjects in the south, making it known that these taxes were to be paid in cacao beans. This led to the beans being used more widely as currency. The early Spanish invaders noted that their prisoners treated the bean with great reverence, and interrogated them to discover its properties. The drink was initially imported to Spain in its original bitter form. However, the Europeans learned to add a sweetener in the form of honey or sugar, and the modern form of chocolate was born.

The Umbrella

The first umbrellas were sunshades or parasols – this is partly because the most advanced civilizations developed in warmer climates. The earliest evidence we have of such umbrellas comes from 2400 BC. In a victory monument to Sargon, king of Akkad (in modern-day Iraq), he is depicted walking ahead of his troops while an attendant holds a parasol over his head to protect him from the sun.

By the first millennium BC, umbrellas had become a status symbol. The wealthiest Egyptians, for instance, looked down on suntans as being characteristic of the ordinary workers in the fields, and the pharaoh and other high-status individuals were often depicted with aides holding a sunshade over them.

The earliest parasols were fairly flimsy and not waterproof, so would have been useless in a rainstorm. For instance, parasols made in China from early in the first millennium BC were made of silk. For an all-purpose umbrella, we have to go forward to the Wei Dynasty (AD 386–533), when umbrellas started to be made of heavy mulberry paper that was oiled to make it resistant to water. From this point onwards the umbrella had a new function: it could protect its owner against a sudden downpour!

A Brief History of the Lavatory

The dilemma of how and where people should ‘go to the toilet’ goes back to prehistory, when a hole in the ground would have been the most common solution. However, lavatories of one sort or another have been in existence for at least five millennia:

• In the Stone Age village of Skara Brae, on the Orkney Islands, archaeologists found what appear to be 5,000-year-old toilets in the stone walls of the houses, above drains that lead away from the buildings.

• From the same period, in the ancient city of Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley in Pakistan, houses have been found with a similar arrangement: brick holes (with the remnants of wooden seats) over a chute leading to a communal drain.

• A palace at Eshnunna in ancient Mesopotamia had a communal toilet, with six seats with raised brick seats in a row.

• In the seventeenth century BC, the Palace of Knossos on Crete featured a sophisticated system in which earthenware pans (in a room with easily cleaned gypsum slabs for walls) were connected to a water supply that flowed through terracotta pipes.

• An Egyptian toilet from about the fourteenth century BC was made from limestone with a keyhole-shaped opening, placed over a removable jar (which had to be cleaned out periodically). A hollow space on either side of the seat contained sand, to be thrown down the hole afterwards.

• The first known portable toilet also comes from this period in Egypt: a wooden stool...