![]()

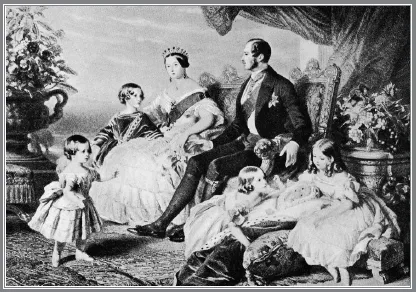

Sons and Daughters

Alongside creating the ideal family, Albert and Victoria had high hopes for a harmonious Europe with an Anglo-German dynasty centred on their family. It was Victoria’s wish that her children should marry for love as she herself had done, but that did not mean the match could not also be politically advantageous. It was generally assumed that suitable candidates would be found among the royal houses of Europe. A British subject, even an aristocrat, was simply not royal and failed to offer the same opportunities for foreign alliance.

Loyal and upright, Albert was devoted to his wife and they both considered sexual morality to be vitally important. This was a cherished value that was to cause more than a little conflict with both Bertie and Affie as they entered adulthood.

To advance their vision of a pro-English Germany, a meeting was arranged at Balmoral in 1855 between Princess Victoria, the Princess Royal, and Frederick (Fritz), Prince of Prussia, who was heir to the German throne. The couple swiftly fell in love. The marriage eventually took place in January 1858 at the Chapel Royal of St James’s Palace in London and they moved to Berlin immediately afterwards. Vicky was just seventeen and both Victoria and Albert were devastated to lose their beloved, clever, eldest daughter. Vicky privately confessed to her mother, ‘I think it will kill me to take leave of Papa!’

In a change of heart from her letter to Princess Augusta of Prussia in October 1856, when Vicky and Fritz were engaged and Victoria was sanguine about the prospect of being separated from her eldest daughter, the Queen admitted to Uncle Leopold:

I feel it is terrible to give up one’s poor child, and feel very nervous for the coming time, and for the departure. After all it is like taking a lamb to be sacrificed.

There was the sudden realization that Vicky would be living abroad: ‘She will return but for a short time, almost as a visitor.’

Victoria also considered that her daughter might be much changed on her future return to England: ‘She will no longer be an innocent girl – but a wife – and – perhaps, this time next year already a mother!’

Letters to Vicky

Vicky’s move to the Prussian court marked the start of a regular correspondence between the Princess and her parents. She wrote weekly to her father detailing court life and politics. The Queen, meanwhile, wrote almost daily letters to her eldest daughter, whom she still tried to direct and control from afar.

Altogether more than 8,000 letters were exchanged between mother and daughter. Queen Victoria’s in particular are remarkably candid and unguarded, perhaps because she sometimes felt as if she were communicating with ‘my sister rather than my child’. Unlike her journals, her letters escaped Beatrice’s later editing and transcribing, and so offer a unique insight into the Queen’s thoughts and character.

Victoria wrote the first of her letters on 2 February 1858, the day that Vicky departed for Germany:

An hour is already past since you left – and I trust that you are recovering a little, but then will come that awful separation from dearest Papa! How I wish that was over for you, my beloved child! … Yes it is cruel, very cruel – very trying for parents to give up their beloved children, and to see them go away from the happy peaceful home – where you used all to be around us! … Poor dear Alice, whose sobs must have gone to your heart – is sitting near me writing to you … Dearest, dearest child, may every blessing attend you both.

Two days later, the Queen’s letter to Vicky revealed how she was coping with her daughter’s absence:

I am better today, but my first thoughts on waking were very sad – and the tears are ever coming to my eyes and ready to flow again … Everything recalls you to our mind, and in every room we shall have your picture.

On 5 February, Victoria’s heartache showed no sign of abating:

You wrote dearest Papa such a beautiful letter, it made me cry so much, as indeed everything does. I don’t find I get any better … God bless you for your dear warm affectionate heart and for your love to your adored father. That will bring blessings on you both! How he deserves your worship – your confidence. What a pride to be his child as it is for me to be his wife!

Victoria’s letters continued with advice, even down to the type of writing paper that Vicky should use. She also issued the odd reprimand when her daughter failed to answer her questions in what she considered to be the right way. While the Queen obviously wanted Vicky to be happy, there is a hint of petulance at any suggestion she might be too happy in her new home:

Pray do answer my questions, my dearest child, else you will be as bad as Bertie used to be, and it keeps me in such a fidget. I asked you several questions on a separate paper about health, cold sponging – temperature of your rooms etc. and you have not answered one! You should just simply and shortly answer them one by one and then there could be no mistake about them. My good dear child is a little unmethodical and unpunctual still … Are you happier than at Windsor? I thought that you could not be. Bertie is shocked at your liking everything so much.

That you are so happy is a great happiness and great comfort to us and yet it gives me a pang, as I said once before to see and feel my own child so much happier than she ever was before, with another … You know, my dearest, that I never admit any other wife can be as happy as I am – so I can admit no comparison for I maintain Papa is unlike anyone who lives or ever lived and will live.

Though she may have been entrusted with many of her mother’s confidences, even Vicky did not escape her personal reproaches:

Do you know that you’ve got into a habit of writing so many words with a capital letter at the beginning? With nouns that would not signify so much, but you do it with verbs and adjectives, which is very incorrect, dear, and would shock other people if you wrote to them so.

I wish you for the future to adopt the plan of beginning your letters with the following sort of headings. Yesterday, or the day before, we did so and so, went here or there, and then where you spent the evening.

At times, the Queen adopted an even more pointed approach:

Your answers yesterday by telegram are not quite satisfactory and you don’t say whether your cold is better, or not. Were you feverishly unwell with it, or not? I get terribly fidgeted at not knowing what is really the matter … I really hope you are not getting fat again. Avoid eating soft, pappy things or drinking much. You know how that fattens.

Prince Albert obviously thought that Victoria wrote too often to her daughter, which in turn forced Vicky to send regular replies:

If you knew how Papa scolds me for (as he says) making you write! And he goes further, he says that I write far too often to you, and that it would be much better if I wrote only once a week! … I think however Papa is wrong and you do like to hear from home often. When you do write to Papa again just tell him what you feel and wish … for I assure you Papa has snubbed me several times very sharply on the subject and when one writes in spite of fatigues and trouble to be told it bores the person to whom you write, it is rather too much!

When the Queen learned that Vicky had twisted her ankle at the beginning of May 1858, she reacted as if her daughter had carelessly injured herself just to upset her mother:

How dreadfully vexed, worried and fidgety I am at this untoward sprain I can’t tell you! How could you do it? I am sure you had too high heeled boots! I am haunted with your lying in a stuffy room in that dreadful old Schloss – without fresh air and alas! naturally without exercise and am beside myself.

At other times, the Queen made light of any problems Vicky might have and was wholly unsympathetic. When the sprain failed to improve, Victoria was less than supportive: ‘I fear you exaggerate as you so often used to do. Others who do not know your disposition think you are really ill! Which you are not!’

However, this was nothing compared to her response to the news that Vicky was pregnant on 26 May 1858: ‘The horrid news … has upset us dreadfully. The more so as I feel certain almost it will come to nothing.’ Not quite the expected reaction from a proud prospective grandmother.

Victoria had previously advised her daughter to avoid pregnancy too early in her married life, effectively saying that Vicky’s birth had ruined the first years of her own marriage:

I cannot tell you how happy I am that you are not in an unenviable position. I never can rejoice by hearing that a poor young thing is pulled down by this trial. Though I quite admit the comfort and blessing good and amiable children are – though they are also an awful plague and anxiety for which they show one so little gratitude very often! What made me so miserable was – to have the first two years of my married life utterly spoilt by this occupation! I could enjoy nothing – not travel or go about with dear Papa and if I had waited a year, as I hope you will, it would have been different.

After coming to terms with her daughter’s imminent motherhood, however, the Queen slightly softened her attitude:

I delight in the idea of being a grandmamma; to be that at 39 (D.V.) [God willing] and to look and feel young is great fun … I think of my next birthday being spent with my children and a grandchild. It will be a treat!

With the birth of her first baby fast approaching Vicky was warned by her mother not to talk to other women about what to expect, ‘particularly abroad, where so much more fuss is made of a very natural and usual thing’. There was not much consolation for the Princess afterwards either. Her labour dragged on for thirty-six hours, with no pain relief, and a fumbled forceps delivery permanently injured baby Wilhelm’s arm. Her firstborn would grow up to become Kaiser Wilhelm II, who would be responsible for setting Germany on a course of action that ultimately led to the First World War.

The Queen’s reassuring but dismissive response to her daughter’s unpleasant experience was, ‘But don’t be alarmed for the future. It can never be so bad again.’

Once the child was born, Victoria was at pains to counsel Vicky against lavishing too much attention on him:

I know you will not forget, dear, your promise not to indulge in ‘baby worship’, or to neglect your other duties in becoming a nurse … as my dear child is a little disorderly in regulating her time, I fear you might lose a great deal of it, if you overdid the passion for the nursery. No lady, and still less a Princess, is fit for her husband or her position, if she does that.

Looking back on her own feelings compared to those of her daughter, she revealed, ‘I never cared for you near as much as you seem to about the baby; I care much more for the younger ones (poor Leopold perhaps excepted).’

In another letter Victoria asked Vicky not to tell her younger sister Alice too much about pregnancy or childbirth, again clearly imposing her own opinion upon her:

Let me caution, dear child, again, to say as little as you can on these subjects before Alice (who has already heard much more than you ever did) for she has the greatest horror of having children, and would rather have none – just as I was when a girl and when I first married – so I am very anxious she should know as little about the inevitable miseries as possible; so don’t forget...