![]()

1

NUMBER

![]()

Chapter 1

TYPES OF NUMBER

Sixty-four per cent of people have access to a supercomputer.

In 2017, according to forecasts, global mobile phone ownership was set to reach 4.8 billion people, with world population hitting 7.5 billion. As the Japanese American physicist Michio Kaku (b. 1947) put it: ‘Today, your cell phone has more computer power than all of NASA back in 1969, when it placed two astronauts on the moon.’

At a swipe, each of us can do any arithmetic we need on our phones – so why bother to learn arithmetic in the first place?

It’s because if you can perform arithmetic, you start to understand how numbers work. The study of how numbers work used to be called arithmetic, but nowadays we use this word to refer to performing calculations. Instead, mathematicians who study the nature of numbers are called number theorists and they strive to understand the mathematical underpinnings of our universe and the nature of infinity.

Hefty stuff.

I’d like to start by taking you on a trip to the zoo.

Humans first started counting things, starting with one thing and counting up in whole numbers (or integers). These numbers are called the natural numbers. If I were to put these numbers into a mathematical zoo with an infinite number of enclosures, we’d need an enclosure for each one:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 . . .

The ancient Greeks felt that zero was not natural as you couldn’t have a pile of zero apples, but we allow zero into the natural numbers as it bridges the gap into negative integers – minus numbers. If I add zero and the negative integers to my zoo, it will look like this:

. . . −6, −5, −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 . . .

My zoo now contains all the negative integers, which when combined with the natural numbers make up the group of numbers called, imaginatively, the integers. As each positive integer matches a negative one, my zoo needs twice as many enclosures as before, with one extra room for zero. However, my infinite mathematical zoo does not need to expand, as it is already infinite. This is an example of the hefty stuff I referred to earlier.

There are other types of numbers that are not integers. The Greeks were happy with piles of apples, but we know an apple can be divided and shared among a number of people. Each person gets a fraction of the apple and I’d like to have an example of each fraction in my zoo.

If I want to list all the fractions between zero and one, it would make sense to start with halves, then thirds, then quarters, etc. This methodical approach should ensure I get all the fractions without missing any. So, you can see that I’m going to have to go through all the natural numbers as denominators (the numbers on the bottom of the fraction). For each different denominator, I’ll need all the different numerators (the numbers on the top of the fraction), starting from one and going up to the value of the denominator.

Fractions

Fractions show numbers that are between whole integers and are written as one number (the numerator) above another (the denominator) separated by a fraction bar. For example, a half looks like:

One is the numerator, two is the denominator. The reason it is written this way is that its value is one divided by two. It tells you what fraction of something you get if you share one thing between two people.

is three things shared between four people – each person gets three quarters.

Once I’ve worked out all the fractions between zero and one, I can use this to fill in all the fractions between all the natural numbers. If I add one to all the fractions between zero and one, this will give me all the fractions between one and two. If I add one to all of them, I’ll have all the fractions between three and four. I can do this to fill in the fractions between all the natural numbers, and I could subtract to fill in all the fractions between the negative integers too.

So, I have infinity integers and I now need to build infinity enclosures between each of them for the fractions. That means I need infinity times infinity enclosures altogether. Sounds like a big job, but luckily I still have enough enclosures.

As the fractions can all be written as a ratio as well, the fractions are called the rational numbers. I now have all the rational numbers, which contain the integers (as integers can be written as fractions by dividing them by one), which contain the natural numbers in the zoo. Finished.

Just a moment – some mathematicians from India 2,500 years ago are saying that there are some numbers that can’t be written as fractions. And when they say ‘some’, they actually mean infinity. They discovered that there is no number that you can square (multiply by itself) to get two, so the square root of two is not a rational number. We can’t actually write down the square root of two as a number without rounding it, so we just show what we did to two by using the

radix symbol:

. There are other really important numbers that are not rational that have been given symbols instead as it is a bit of a faff to write down an unwritedownable number:

π,

e and

φ are three examples that we’ll look at later. We call such numbers

irrational, and I need to put these into the zoo as well. Guess how many irrational numbers there are between consecutive rational numbers? That’s right – infinity! However, I can still squeeze these into my infinite zoo without having to build any more enclosures, although Cantor might have a thing or two to say about that (see

here).

Squares and Square Roots

When you multiply a number by itself, we say the number has been squared. We show this with a little two called a power or index:

3 × 3 = 32

Three squared is nine. This makes three the square root of nine. Square rooting is the opposite of squaring. The square root of sixteen is four because four squared is sixteen:

Numbers like nine and sixteen are called perfect squares, because their square root is an integer. Any number, including fractions and decimals, can be squared. Any positive number can be square rooted.

For much more information about this, see here.

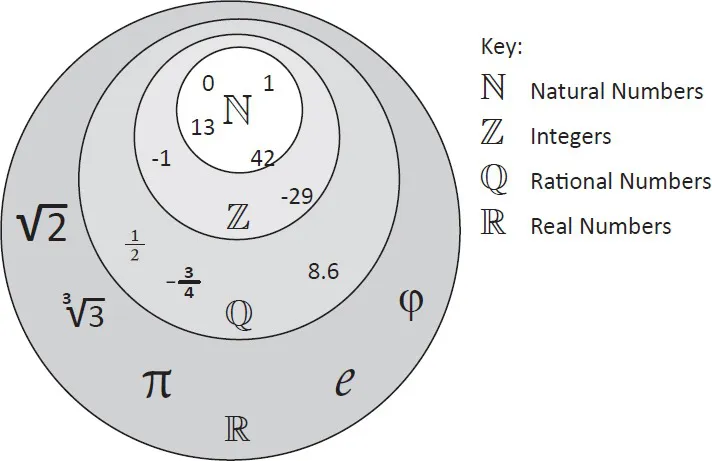

When we put the irrational numbers together with the rational numbers we have what mathematicians call the real numbers. If you’ve spotted a pattern in what went before, you’ll suspect that there are also not-real numbers and you’d be right. However, I’m going to stop there and name my zoo The Infinite Real Number Zoo. Most zoos sort their animals out by type, so I could organize mine into overlapping groups of types. The map might look like this, and I’ve put a few must-sees in to help you plan your day out:

The Infinite Real Number Zoo

I must own up to the fact that my zoo owes a lot to the German mathematician David Hilbert (1862–1943). He made great contributions to mathematics but is best known for his advocacy and leadership of the subject. In 1900 he produced a list of twenty-three unsolved problems – now known as the Hilbert problems – for the International Congress of Mathematicians, three of which are still unresolved to this day. The thought experiment Hilbert’s Hotel, the source for my zoo, concerns Hilbert’s musings on a hotel with an infinite number of rooms filled with an infinite number of guests. Hilbert shows that we can still fit another infinite number of guests into the hotel if we can persuade all the initial guests to move to the room with a number double their current room number. The current guests would all now be in even-numbered rooms, leaving the odd-numbered rooms (of which there are infinitely many) for the new arrivals.

![]()

Chapter 2

COUNTING WITH CANTOR

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) came up with a nice puzzle known as Galileo’s paradox while under house arrest in Italy for his heretical belief that the earth went around the sun.

It says that while some natural numbers are perfect squares (see here), most are not, so there must be more not-squares than squares. However, every natural number can be squared to produce a perfect square, so there must be the same number of squares as natural numbers. Hence, a paradox: two logical statements that cannot both be true.

Number theorists, as I’ve said, tackle the nature of infinity and its bizarre arithmetic. Set theory, which is what we were doing when we looked at the infinite mathematical zoo, was invented by the German mathematician Georg Cantor (1845–1918). He figured out that there are actually different types of infinity. He worked on the cardinality of sets, which means how many members of the set there are. For instance, if I define set A as being the planets of the solar system, the cardinality of set A is eight. (For more information about why Pluto is no longer a planet, see here.)

Cantor looked at infinite sets too. The natural numbers are infinite, but Cantor said that they are countably infinite because as we count upwards from one, we are moving towards infinity, making progress. We’ll never get to infinity, but we can approach it. Cantor defined the set of natural numbers as having a cardinality of aleph-zero, or ℵ0 (aleph being the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet). Any other set of numbers where you can make progress also has cardinality ℵ0. So if I include the negative integers with the natural numbers, I can still make progress counting through them, so the set of integers also has cardinality of ℵ0.

If my s...