![]()

EVOLUTIONARY JOURNEYS

1

The Myth of No Limits

“Once there were bacteria, now there is New York.”1 No fish swam above the Archaean stromatolites, no rainforests swathed the tropics of the Cambrian, no cities lined the seaboards of the Cretaceous Tethyan ocean. Through time the biosphere reveals a story of ever-greater complexity. So too, as Darwin outlined, we are taught to see this as a step-by-step process. Undeniable, but things are not quite so simple, either literally or metaphorically. First, New York does indeed stand where once only microbial mats flourished, but the bacteria are still with us (which is just as well).2 More importantly, however deep we choose to climb down the phylogenetic ladder, true simplicity is strangely elusive. Second, the implication of the unfolding tapestry of evolution is that it is effectively without limits or boundaries. A closer examination suggests that—with one crucial exception—this is not the case.

INVENTING THE EUKARYOTE: FIRST SIMPLE, THEN . . . ?

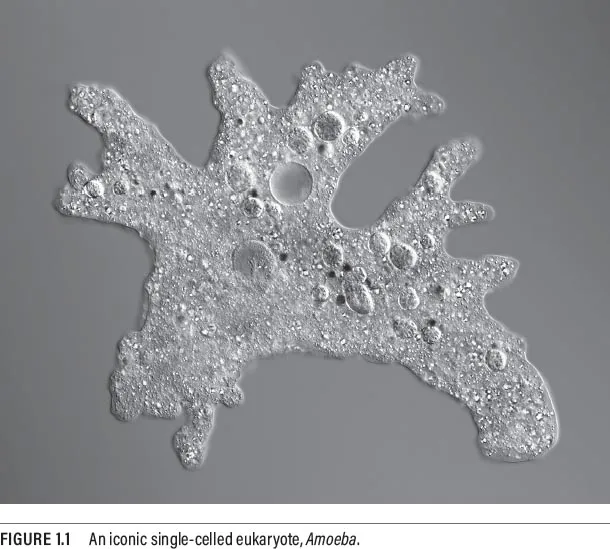

What circumscribes life is an oddly neglected topic, but perhaps this is less surprising when there is so much to try to understand in the grand narrative of evolution. Central to this task is the identification of major transitions in the history of life,3 epochal rearrangements that may build on existing diversity but usher in new worlds. Language, or perhaps more generally the human mind, is one such example; the evolution of multicellularity is perhaps another. But assuredly neither of these breakthroughs would have happened without the evolution of the eukaryotes, which were originally single-celled organisms, as we still see in the living Amoeba (figure 1.1). The subsequent diversifications of the eukaryotes have been staggering, populating the planet with mushrooms, sequoias, sperm whales, and for good measure giant kelp. If the starting point was a single cell then so too surely it was gratifyingly simple? Correspondingly we can then sit back to enjoy a story of unfolding complexity? Such would be the intuitive assumption. Given a rudimentary fossil record that scarcely preserves any cellular details and involves events that were probably underway more than two billion years ago, one might enquire how we would ever know one way or the other. The answer is relatively straightforward inasmuch as every living organism has an evolutionary footprint that will betray its origins.

Not that tracing these various spoor is a simple exercise. Form may be altered almost beyond recognition, and evolutionary convergence can fool even the seasoned observer (chapter 2). Genomes may be scrambled, bloated, or stripped down, and foreign genes can be parachuted into the cell in the process known as horizontal gene transfer. Neither, despite enormous advances in the technologies of evolutionary analysis, is it possible (or even necessary) to analyze every species. So we take representatives to serve as proxies for each of the major groups of eukaryotes. These, by general consensus, number five or six. Should you wish to know, you are a unikont, which among other things explains why my sperm have a single flagellum. To be slightly more specific we are opisthokonts (the flagellum is located at the posterior end of the sperm), thus placing us humans relatively close to the toadstools. These very major groups are, of course, further subdivided so that in turn we are also animals (metazoans), vertebrates, primates, and a very peculiar sort of ape (chapter 5).

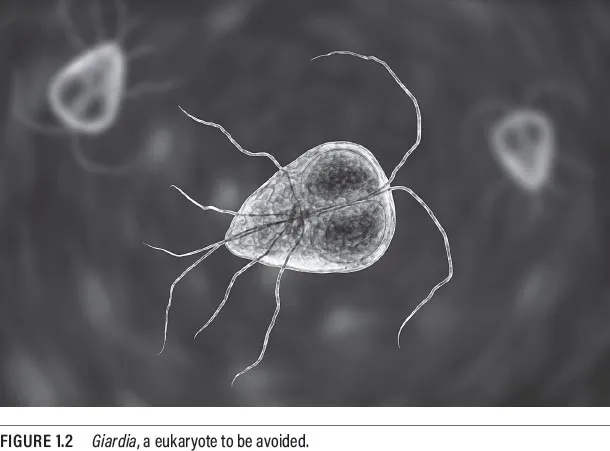

In any event, all these groups, including the unikonts, stem from the ancestral eukaryote. We can then infer the relative complexity of this ur-eukaryote on the reasonable premise that if all the major groups share particular genes, molecules, or cellular structures, then we can be pretty confident that so too did the ancestral cell—which usually shelters under the acronym LECA, for “last eukaryotic common ancestor.” It is now clear, for example, that LECA came equipped with mitochondria and these were essential for its (and ours) respiration. Mitochondria also serve as a canonical example of so-called endosymbiosis. That is, these tiny organelles were once free-living bacteria (specifically α-proteobacteria) that surrendered their freedom (or brokered some other agreement) to become permanently associated with the eukaryotes. Mitochondria are almost universal among eukaryotes. However, parasitic forms, such as that little parasitic horror Giardia (figure 1.2), lack mitochondria. In the heady earlier days of these studies, when the outlines of eukaryotic phylogeny were emerging, such forms were thought to give a glimpse of the very first stages of their evolution. But this is not so: the mitochondria are not so much lost as converted into a rudiment labeled the mitosome (consistent with Giardia’s effectively anaerobic existence).

Yet even if mitochondria were in place at the very earliest steps in eukaryotic history (or perhaps were even a pre-eukaryotic acquisition), we should still expect to see stories of unfolding complexity as each of the major groups elaborated in their different ways the elementary scaffolding provided by LECA. The exact reverse turns out to be the case: far from being simple, this common ancestor was astonishingly complex. To explain just how complex is almost as challenging as understanding the innumerable intricacies of the eukaryotic cell itself. Without being overreductionist, one can consider the cell as a submillimetric factory, where master plans are executed, messages sent and received both within the cell and with the outside world, routine maintenance is undertaken, and disaster squads are always poised for action. It may sound somewhat routine, but what is truly dazzling is the cellular integration of function and efficiency in an immense series of complex cycles and networks.

Given that these arrangements did not fall out of the sky,4 what then can we infer about the cellular situation of LECA? Let us start with the genome, where three items command our immediate attention. That the earliest eukaryotes engaged in cell division (mitosis) is unremarkable; much more surprising is that they were also capable of sexual reproduction (meiosis), even though this calls on sophisticated processes for the all-important exchange of genetic material between “male” and “female.”5 Second, eukaryotic DNA must, of course, issue the instructions; the sections that are involved with the actual coding (the exons) are, however, almost always interspersed with other sections of DNA—the introns—which ultimately have to be snipped out. Typically single-celled eukaryotes have relatively few introns whereas multicellular groups (notably plants and animals) are intron-rich. The default assumption would be that LECA was intron-poor and as time elapsed more and more introns were acquired, but the exact reverse turns out to be the case: LECA was extraordinarily intron-rich,6 with introns perhaps accounting for two-thirds of the genome. What advantage this may have conferred is much less clear, but is another pointer to the complexity of this “primitive” genome. This is echoed by the mechanisms involved with the transcription of genes (where the RNA is read off the DNA) and the associated regulation (such as the employment of homeodomains). Once again, far from being simple trial attempts, the regulatory arrangements inferred in LECA match the complexity of living eukaryotes.7 Indeed, wherever one looks in terms of early eukaryote genome management it is the same story of early complexity.8

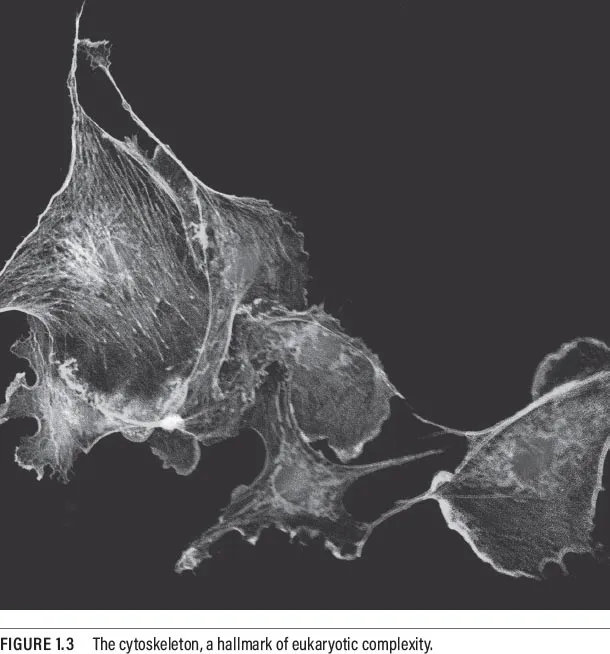

Beyond this hive of industry located in the nucleus, the rest of the cell contains the intricate scaffolding of the cytoskeleton (figure 1.3) (including filaments and microtubules) and an array of endomembranes such as the Golgi apparatus (which, once again, has a very deep ancestry9). In this regard, the eukaryotic cell is exceptionally dynamic, not least with its sophisticated molecular motors and ceaseless trafficking of various compounds. The point about these systems is not only are they very sophisticated nanomachines,10 but most of the different protein families were already up and running in LECA.11 Neither can any cell operate unless instructions can be dispatched and acted on and, just as importantly, incoming information from the outside world can be interpreted in a process known as transduction. Photons triggering an electrical response in the retina is a familiar example.

One important ingredient in these sorts of processes are small proteins known as ubiquitins. These “talk” to all sorts of other proteins and thereby control what they can do. As the name of the proteins and the process (ubiquination) suggest, these activities in the cell are all pervasive and central to eukaryotic existence. So does LECA possess a prototype ubiquination, and does the subsequent history of the eukaryotes demonstrate a series of subsequent elaborations? On the contrary: the ubiquination tool kit possessed by LECA was as complex as found today.12

What about the activities linked to signal transduction? Key to these processes are proteins known as guanine protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). In us, for example, our capacity to taste, smell, and see all depends on GPCRs. The overall diversity and range of functions of these GPCRs, however, extend far beyond their involvement in sensory systems. Once again, one might infer a story of steadily unfolding complexity in the evolution of the eukaryotes. But when we turn to LECA, it is evident that the majority of GPCR families were already in place.13

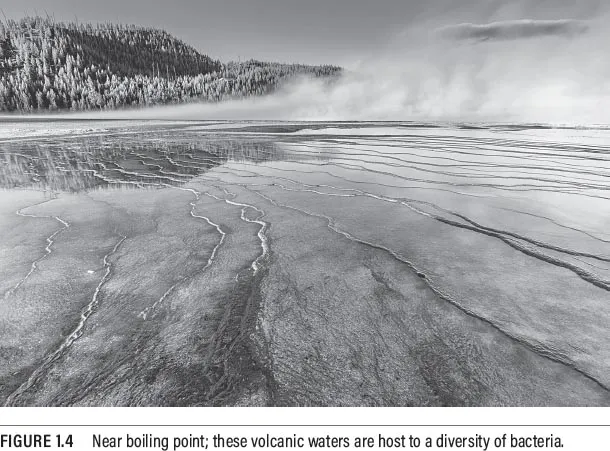

So LECA was the exact reverse of simple,14 but its unexpected complexity begs two questions. First, LECA obviously did not step out of thin air—they must have emerged from among the prokaryotes. They too can hardly be described as simple, so perhaps some of the complexity of LECA is inherited? Second, sheep and palm trees are among the innumerable descendants of LECA, but why then is this ur-eukaryote so much more complex than Darwinian orthodoxy would proclaim? With regards to the first point, the ancestry of the eukaryotes increasingly points to the archaeal bacteria playing a central role,15 with the Lokiarchaeota being pinpointed as prime suspects.16 More generally these bacteria are referred to the Asgard group, with a penchant for scalding-hot hydrothermal vents (figure 1.4). A propensity for extreme environments is something of a hallmark of the Archaea and perhaps may also be a useful fingerpost toward the further reaches of extraterrestrial life (chapter 6).

In any event, like all the prokaryotes these bacteria are very sophisticated. So too it is apparent that a good part of the machinery that the eukaryotes rely upon is already present in the prokaryotes.17 It would be surprising if it were not. There are, however, two important qualifications. First, the uses to which these proteins are put are often quite different in either group. Just as important, the molecular systems in the prokaryotes seldom show the range and diversity that is already evident in LECA. Obviously there was evolutionary continuity between the last prokaryote and first eukaryote, ...