- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

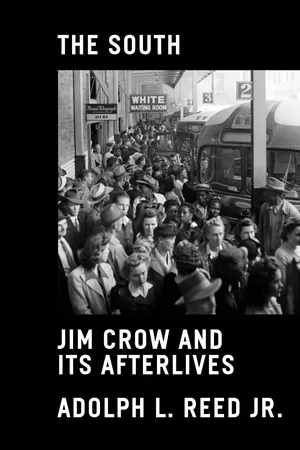

The last generation of Americans with a living memory of Jim Crow will soon disappear. They leave behind a collective memory of segregation shaped increasingly by its horrors and heroic defeat but not a nuanced understanding of everyday life in Jim Crow America. In The South, Adolph L. Reed Jr. - New Orleanian, political scientist, and, according to Cornel West, "the greatest democratic theorist of his generation" - takes up the urgent task of recounting the granular realities of life in the last decades of the Jim Crow South.

Reed illuminates the multifaceted structures of the segregationist order. Thanks to his personal history and political acumen, we see America's apartheid system from the ground up, not just its legal framework or systems of power, but the way these systems structured the day-to-day interactions, lives, and ambitions of ordinary working people.

The South unravels the personal and political dimensions of the Jim Crow order, revealing the sources and objectives of this unstable regime, its contradictions and weakness, and the social order that would replace it.

The South is more than a memoir or a history. Filled with analysis and fascinating firsthand accounts, this book is required reading for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of America's second peculiar institution and the future created in its wake.

Reed illuminates the multifaceted structures of the segregationist order. Thanks to his personal history and political acumen, we see America's apartheid system from the ground up, not just its legal framework or systems of power, but the way these systems structured the day-to-day interactions, lives, and ambitions of ordinary working people.

The South unravels the personal and political dimensions of the Jim Crow order, revealing the sources and objectives of this unstable regime, its contradictions and weakness, and the social order that would replace it.

The South is more than a memoir or a history. Filled with analysis and fascinating firsthand accounts, this book is required reading for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of America's second peculiar institution and the future created in its wake.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The South by Adolph L. Reed Jr.,Adolph Reed Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Quotidian Life in the 1950s and 1960s

The regime was less harsh in New Orleans in some respects than in other big cities in the region. In some ways it’s never been a typically southern city. Even the local speech isn’t typically southern. When I moved to North Carolina to go to college, I had to train my ear to hear properly what we usually think of as southern accents and to make class and regional distinctions among them. Within a few years after leaving the South in the early 1980s, I found that my ability to hear those accents naturally, without straining to understand, had dissipated; for a while, on trips back I had to pause and translate communications in my head, as one does with a seldom-used second language.

On the one hand, the local political culture in New Orleans managed, and still does, to combine features of conventional southern and Latin or Caribbean Catholic conservatism. On the other hand, the Big Easy and the City That Care Forgot monikers, though primarily tourist industry hype, reflected something genuine—a laid-back local style that could wink more easily than most at petty, private transgressions, so long as they were conducted unobtrusively or, as Cubans today describe the gap between official policy and unofficially recognized practice there, bajo la mesa (under the table). No doubt many facts nudged in that direction: the port; the diversity of immigrant populations, often with their own living histories of discrimination (as, for instance, the group of eleven Sicilians lynched in the city in 1891 for allegedly assassinating the police chief or the tens of thousands of Irish canal diggers who died and were buried in the New Basin Canal in the 1830s); and the democratizing realities of Mafia-led wide-openness. (Prideful local lore has it that the Black Hand extortion arrived in the city from Sicily before it showed up in New York.) And the city’s quirks of housing occupancy, which stemmed from its age and length of settlement, may also have had some effect.

In much of the city, the pattern of residential segregation was more like a checkerboard than racial separation on strict geographical lines. Blacks and whites frequently lived in the same neighborhoods, on different sides of the street or different ends of the block. There was not normally a lot of interaction across racial lines; sharing recipes and popping over for neighborly cups of coffee were rare occurrences at best. Black and white residents didn’t so much share neighborhoods as coexist in them. They presumably had their neighborhood life, and we had ours—all in the same space. Some whites obviously recoiled at having black neighbors and went out of their way to underscore the barriers between them and us. Some were aggressively hostile and passed that disposition on to their dogs and children. Many were content to live peacefully, if not amicably, within minimal standards of racial distance that were generally faithful to the norms of segregation but tacitly improvised by blacks and whites mutually—for example, no expectations of entering each other’s homes, no joint social activities or excursions out of the neighborhood.

Many of those white people who were cordial in the neighborhood’s everyday confines would snub or feign not to recognize their black neighbors when encountering them elsewhere. To some extent, we accurately and justifiably understood that behavior as two-faced, particularly when it came from those who seemed to display greater than usual warmth and fellow-feeling within the neighborhood’s cloister. In retrospect, though, most white people were also confronted with the challenge of devising appropriate ways of being within a social order they didn’t create and that came to them as the world’s unquestioned and unquestionable facts of life. And the repercussions of being defined as a “nigger-lover” threatened to be almost as great as being defined as black. These could go beyond social ostracism and scorn; they could affect employment and other aspects of material well-being. People should be commended and appreciated when they are prepared to face such risks for decency or principle; it’s not necessarily damnable when they aren’t, though this insight comes much more easily decades after the fact. And I’ve gone unrecognized frequently enough—both in the South and elsewhere—by familiar white colleagues and coworkers in public situations outside our shared normal contexts that I’ve realized that many white people’s social perception has been trained not to distinguish us as individuals within their environment. It’s not so much that we “all look alike” to them, as the cliché goes. Many white people simply and genuinely do not see us distinctly unless they have specific, clearly defined expectations of doing so. Thus, Sidney Poitier, Danny Glover, and Chadwick Boseman each has been cast to play Thurgood Marshall in films though none of them bears even the most fleeting physical resemblance to him. By contrast, think of the efforts taken to cast actors who resemble, or can be made up to resemble, white historical figures like Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Richard Nixon, Roger Ailes, Hitler, or even Babe Ruth.

Those neighborhoods were by no means idyllic settings of racial harmony. They were clearly segregated. Within those limitations, however, in little ways the fact of cohabiting the same daily terrain subverted racial distance and, to that extent also the Jim Crow regime, if only at its margins. Men now and again would be drawn across the color line to kibitz or join in some spontaneously collaborative project like working on a car. Sometimes they would cross the line, at least for an inning or two, to join the small congregations that formed on porches, front yards, and sidewalks to listen to and comment on radio broadcasts of baseball games. These were first the St. Louis Cardinals, and then the Houston Astros, née Colt 45s, who had the supplanting virtues of closer proximity and featuring hometown hero, Rusty Staub, in the lineup. Occasional conversations, often only exchanges of patter, across backyards, from porches and stoops or in pedestrian encounters, about mutual, if superficial, concerns—the heat of the day, whether enough rain would come to counter the sun’s scorching of plants and yards, the approach of a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico, the behavior of rambunctious neighborhood kids, how gardens progressed and the quality of the fruit on backyard trees, prices and offerings at the corner stores, whose pipes had burst in an uncommon freeze—established moments of recognition of equivalent humanity, commonality, and connection as individuals. News that eggplants, satsumas, Creole tomatoes, crawfish, or mirlitons had appeared in markets, announcing their seasons’ arrival, was information much too vital to be blocked by the color line.

Catholicism similarly could be a mild solvent in that very Catholic city, particularly at the level of the neighborhood parish. Catholic schools were racially segregated until 1962, when they were desegregated at all levels at once without major incident. This occurred two years after the public schools implemented a phased desegregation plan that provoked a months-long white uprising more generalized and at least as vicious as Little Rock had experienced in a narrower compass three years previously. The Church was hardly a beacon of racial equality and justice. However, despite the Archdiocese’s accommodation and embrace of segregation, including the insane indignity of separate seating at Mass and distribution of Communion practiced in white parishes through the 1950s (though, curiously, confessional lines weren’t segregated), at least on going to and coming from, entering and exiting, the parish church, black and white neighbors who were co-parishioners encountered each other on a more public plane that remained anchored to the neighborhood. The parish’s organic links to the neighborhood elicited passing exchange of convivialities that could affirm in a public setting acknowledgments of equal humanity enacted more privately on the block, but could do so without the higher stakes associated with recognition in settings entirely divorced from the neighborhood. This effect was certainly marginal. Even those little encounters were too public for many whites to feel comfortably convivial. And interracial attendance at Mass wasn’t the norm. Most black Catholics usually attended churches linked to the segregated black parochial schools. (In high school, my friends and I became connoisseurs of the norms of different parishes, as we shopped around among the smorgasbord of Sunday Mass offerings, sometimes seeking the latest, or the briefest, or the most conveniently located in relation to whatever other plans we had.)

These features of local everyday life and the city’s size and its extent of commercial and industrial development increased the likelihood of black/white encounters that spontaneously took the shape of normal human interactions. This likelihood was greater when those encounters were outside the spotlight of public scrutiny, and it was diminished in moments of politically supercharged white supremacist fervor. Even then, though, it did not disappear entirely. A couple of instances from my own experience may illustrate this kind of encounter and its possible, if limited, significance.

When I was in the ninth grade, in either late 1959 or early 1960, a couple of friends and I often walked about seven blocks from our school on Magazine Street in the city’s Uptown section to ride the St. Charles streetcar at least part of the way home. We took this route, even though the bus that stopped in front of the school was more convenient and arguably more direct, partly to dawdle and hang out and partly because both the walk and the streetcar ride were visually pleasant and serene. On the walk we had fallen into the practice of stopping at a little mom-and-pop store on Soniat Street to buy bits of the junk kids buy after school. Before long, we began to test our mettle at shoplifting. On my first or second attempt I was caught boosting a bag of potato chips or some such. The proprietors, a white couple (as I look back on it, they were probably in their late thirties), nabbed me and wouldn’t let me leave with my friends. I was terrified. By that time, I knew enough about the Jim Crow world to imagine, first, the horror of the police and then being sent to Angola, the state penitentiary, or at least the juvenile reformatory—the “training school” in Baker, near Baton Rouge. Both facilities, especially Angola, were routinely held over our heads by family and other adults as the terminal destination toward which bad behavior would take us. That warning applied to violations of parental rules as well as to more public transgressions that could lead to contact with the Jim Crow criminal justice system. Even now, when I hear the word Angola, or even see it on this page, I can feel a small, internal shudder.

To my grateful surprise and tremendous relief, the couple sat me down on the store’s stoop and talked to me, more like concerned parents or relatives than as intimidating or hostile storekeepers. They said that I seemed like a good kid, that they weren’t going to call the police or my parents, but that I should take a lesson from this incident and not try anything like it again. They explained that I might not be so fortunate next time as to be caught by people as decent and understanding as they were and that, as a result, I could end up in a lot of trouble and maybe ruin my life. They elicited assurances that I’d seen my error and wouldn’t repeat it. Then they let me leave. In effect, they treated me without hesitation as I suspect they’d have hoped for a child of their own to be treated in a similar position, notwithstanding the prevailing white supremacist codes that would dictate otherwise. I have no clue how they might have responded to the school desegregation crisis that hit the city the next school year or any other public issue bearing on racial equality. I know what would make for an uplifting story, but I have no illusions. All I know is that, if they had acted that afternoon in accord with the dictates of the Jim Crow social order and not seen me as they did, I could have, even with the relative insulation of class position, wound up at Baker.

The second incident occurred the previous summer and also involves a mom-and-pop store family. My neighborhood was in a section of the Hollygrove area, nestled between the Airline Highway and what had been a section of New Basin Canal, which was then drained and filled with the clam, mussel, and oyster shells that qualified as gravel in New Orleans. Shortly before I began high school, it was paved over to become the Pontchartrain Expressway and eventually part of Interstate 10. The triangular neighborhood’s third boundary was the New Orleans Country Club, where many of the adult black male residents worked for some period as golf caddies, including our next-door neighbor who worked there all his life. That was where our section of Hollygrove’s most distinguished product, the legendary local vocalist, Johnny Adams, developed his lifelong love for the game. Other men worked as longshoremen or merchant seamen; some worked as porters, laborers, or in more skilled jobs in the building trades—plasterers, painters, bricklayers—and a few worked at the Kaiser aluminum plant or other factories. There was a smattering of Protestant ministers, including Johnny’s father, a couple of physicians, a few small business proprietors, and a complement of public schoolteachers, including several women. Most of the women who worked, however, were domestics. It’s instructive that I never had any notion what any of the white Hollygrove residents did for a living—except, that is, for the Gagliano family.

Two corner stores, a block apart, mainly served my immediate slice of Hollygrove, Tony’s and Oddo’s. “Mr. Tony” Gagliano and his family lived in the long, shotgun structure that housed their store, which was a half-block away from my house, at the intersection of my street, Pear, and Gen. Ogden. Oddo, whose store was a block farther away on Gen. Ogden, lived in the Metairie suburb, though he also may at one time have lived above his store. For years I wondered who this Gen. Ogden was and what he had done to warrant naming a street after him. I was bemused to learn decades later that he had been commander of the supremacist Crescent City White League’s murderous 1874 insurrection against the Reconstruction government and its interracial Metropolitan Police. This “Battle of Liberty Place” was commemorated with a monument erected at the foot of Canal Street in 1891 and that immediately became a rallying point for the lynchers of the eleven hapless Sicilians and for many other racist initiatives spawned in the city thereafter.

The Gaglianos were generally regarded as decent and fair, though most black patrons maintained the cautious skepticism that would mediate any commercial relationship in an environment in which legal recourse couldn’t be assumed even as a deterrent. “Mr. Tony”—the appellation was mutual; my grandparents were Mr. and Mrs. Mac to them—and his wife seemed almost always to chat freely and unguardedly with adult patrons, white and black, sharing neighborhood gossip, making solicitous inquiries about health and family plans and the like, and comparing notes on their own daily and family concerns. Usually they, especially Mrs. Gagliano, would ask kids about school, vacations, and such matters, and, if the kids were alone and their parents or guardians hadn’t been in the store recently, inquire after them and send greetings back with the youngsters. Though Mr. Gagliano in particular could seem rather gruff on occasion, as a rule they presented themselves in a fashion best described as cordial to friendly and, well, neighborly.

Oddo’s reputation was a different kettle of fish. Neither he nor his wife was cordial, and they were frequently characterized as dishonest and “mean,” if not “prejudiced.” Several families wouldn’t send children to his store alone for fear of his shortchanging them. A running joke among the black neighbors was, on learning that an unwed girl was pregnant, to suggest that she had gotten the baby at Oddo’s because he tried to sell black people everything else. Like the Gaglianos, the Oddos were Italian Americans, but people would sometimes insist that Oddo was Jewish, citing his alleged business practices and mercenary demeanor to counter dissenters from this view. It would be a mistake to understand this stereotyping as reflecting committed anti-Semitism, however, as it would be to take references to the Gaglianos as “dagoes” as indicating actively anti-Italian sentiments.

Anyway, that summer I obtained my first (and, it turned out, last) remote-controlled model airplane. I was quite excited about it but leery of the combination of gasoline engine and whirring propeller that had to be dealt with to fly it. It just seemed that there was a lot involved in that proposition that could go wrong, with serious injury as a result. As it happened, the Gaglianos’ son, Tony Jr.—about five or six years my elder, as I recall—was a model plane buff. Probably as the result of a casual conversation with some adult in my family, he came over to help me prepare the plane for flight. We spent much of an afternoon in my backyard with him instructing me and helping me overcome my anxiety. It was an entirely unstrained interaction. He was empathetic and reassuring and encouraging in a manner that I expect a supportive black teenager would have been. We talked a little about our lives, school, sports. When he was confident that I could handle the plane on my own, he left. I thanked him profusely; he said that it was nothing and that he was happy to help me out. I never ran across Tony Jr. again. There was no reason to: he had his life; I had mine. Again, I have no idea what he or his parents would have said if asked to declare themselves about the Jim Crow regime; they very well could have proclaimed it to be the law of God and nature. Yet they were all clearly capable of dealing with black people as they would any other human being they considered as no different from themselves, and they did so spontaneously and without apparent effort.

Within a few years Oddo closed his store and left. Several years later the Gaglianos did the same. The Gaglianos had been at it long enough to want to retire; they’d run the store at least all my life, and who knows how long before. They also had been fretful about competition from the chain supermarkets that had opened not far from our enclave. Black neighbors surmised that they all had made money for a comfortable retirement off black Hollygrove and that the Gaglianos raised their kids and then moved to Metairie like Oddo. They well may have been correct.

Black New Orleanians’ views of Jews and Italians under Jim Crow were complicated. Both populations were certainly considered white in all meaningful senses of that classification; yet black people commonly characterized them as at the same time lying somewhere between blacks and whites, typically with the implication that they were, or should be, more sympathetic (or at least less bigoted) because other whites discriminated against them as well. Jews were prominent in the city’s philanthropic community, especially those endeavors associated with black racial uplift. The most substantial benefactors, Edgar Stern and his wife Edith Rosenwald Stern, heiress to the Sears Roebuck fortune, were primary patrons of black institutions, notably Dillard University and the Flint-Goodridge Hospital, and were instrumental in the development of Pontchartrain Park, one of the first suburban-style housing subdivisions for blacks in the country. Anti-Semitism in New Orleans was garden variety—a casual expression of the panoply of petty stereotypes and exclusion from many of the upper class’s social clubs and voluntary organizations. That is, talk of blood libel or international Jewish conspiracy was not common, although militant white supremacists denounced Jews as agents of race-mixing.

The closest there was to an open effort to mobilize anti-Semitism politically during the postwar decades didn’t get off the ground and was ironically misplaced. The local Schwegmann Brothers Giant Supermarket chain was a forerunner of today’s big-box stores. Between the late 1940s and the early 1960s it grew to eighteen stores in the area, with the largest a 155,000 square foot location that was at the time the largest supermarket in the world. As one of its advantages of scale, Schwegmann’s practiced discount pricing, in contravention of vestigial “fair trade” laws that prohibited the practice. An additional point of comparative advantage was that Schwegmann’s stores opened early on Sundays, breaking with custom rooted in blue laws, which limited shopping on Sundays. Competitors challenged the discount pricing in court but also objected to the stores’ Sunday schedule as unfair; some denounced the policy as un-Christian, which was clearly intended as an anti-Semitic barb, based on the erroneous assumption that the Schwegmann chain was Jewish-owned. The Schwegmann family was not Jewish.

Italians were viewed more broadly as not exactly white, perhaps in part because of their own history in the city. Another factor was that the dark-complexioned Sicilians shaded phenotypically into indistinguishability from the black Creole population. Uptown, white upper-class prejudice against Italians persisted at least through most of the twentieth century, to the extent that in 1977 many Uptown whites supported Ernest N. “Dutch” Morial, who became the city’s first black mayor, as more palatable racially than Joe Di Rosa, his Italian American opponent.

The textures in the Jim Crow fabric as it was woven in New Orleans convey a sense of how racial segregation as an ideology, a set of official institutions and cast of mind, could be suspended, or at least overlooked temporarily, in the imperfectly chartable realm of personal interaction and daily life, in shared neighborhoods and elsewhere. I don’t mean to suggest that these little subversions were unique to New Orleans. On some scale they could have occurred anywhere and almost certainly did in most places with greater or lesser frequency. I do think that they were more likely in places like New Orleans, where the social terrain on which they could occur—the gray area of personal encounter where the codes of subordination’s guidelines were less clear and the options more flexible—was larger than in most places and more difficult to avoid.

I also don’t mean to exaggerate their significance. To be sure, we were vulnerable to white caprice, unjust laws and unequal enforcement, and all the material inequalities—occupational segregation, overt employment, income, housing, and financial discrimination—that were thus enabled. (I recall boiling with anger on the bus ride home from high school when we passed the hypocrisy chiseled across the Orleans Parish Courthouse portal: “The Impartial Administration of Justice Is the Foundation of Liberty.”) We were, by state law, municipal ordinance, and unofficial practice, no better than second-class citizens, and we perceived the role of the police as somewhere between antebellum slave patrols and an occupying army, though without that terminology’s pithiness and rhetorical clarity.

Nor would I suggest that those instances of common human recognition were conscious deviations, politically charged moments stolen by conspirators. They were not. If anything, they could exist only as reflexes, well below the radar scope of political consciousness. And they were extremely fragile for that reason. They could easily be undone by political climate changes that extended white supremacy’s radar range. One of the schools—then named for Judah P. Benjamin, the Jewish former U...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Quotidian Life in the 1950s and 1960s

- 2. The Order in Flux and Being in Flux within the Order

- 3. “Race” and the New Order Taking Shape within the Old

- 4. The New Order and the Obsolescence of “Passing”

- 5. Echoes, Scar Tissue, and Historicity

- Notes