![]()

1

The Birth of a Holy City

4000 BCE TO SECOND CENTURY CE

The paradox of Jerusalem can be summed up in a few words: a town of no major strategic importance, lacking desirable natural resources, has become the nerve center of a regional conflict with global repercussions, and its name, today pronounced by millions of people in their weekly liturgical assemblies, symbolizes a universal eschatological hope.

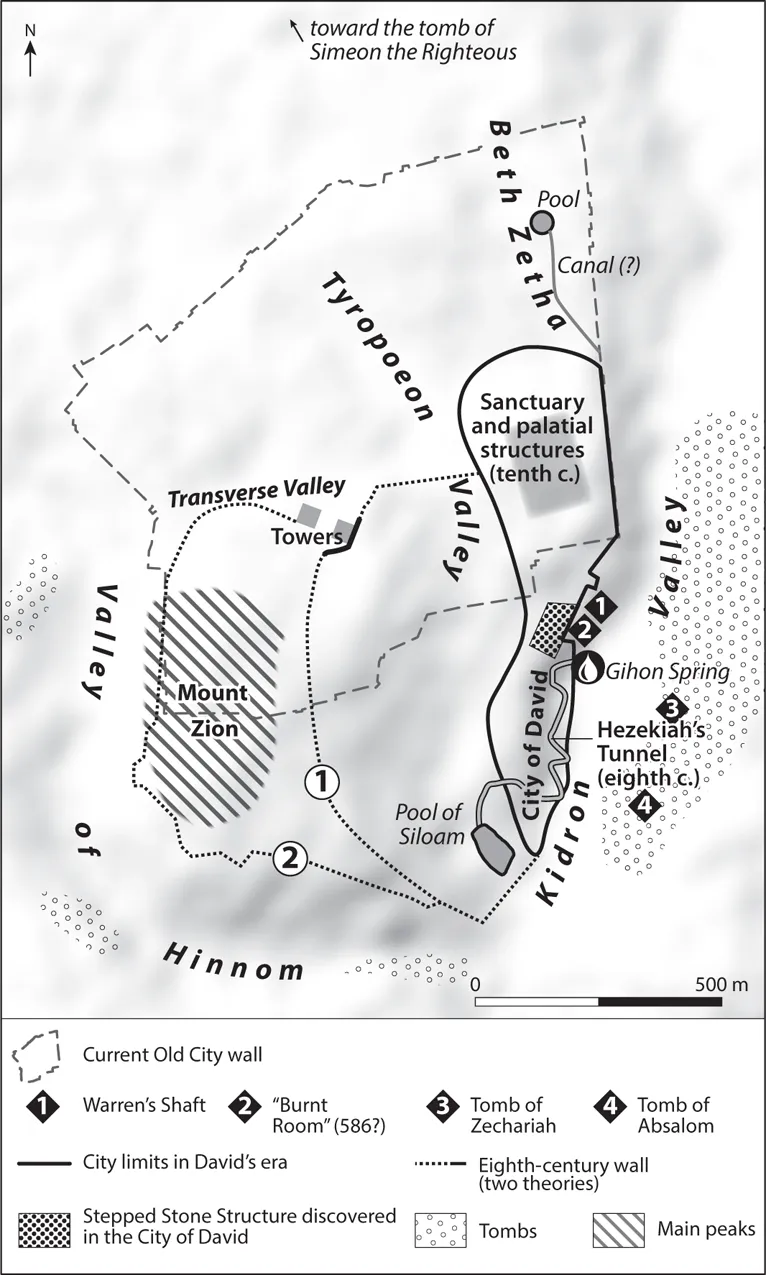

Jerusalem’s setting has, however, many handicaps (see map 1 in the introduction). At the heart of a mountainous zone, it is away from the region’s major trade routes; the main road linking Transjordan to the coastal plain passes north of Jerusalem. The first urban cluster entirely covered a rocky spur at the site today called the City of David. This hill is situated below a rise that slightly dominates it—the Temple Mount, to the north, the current Esplanade of the Mosques—which was further raised later to create a vast platform capable of containing the whole cult complex erected by that great builder King Herod. Between the Temple Mount and the rocky spur with the first urban cluster, we can moreover distinguish an intermediary space, the Ophel, which housed a specific quarter during the city’s development in biblical times. The hills to the west (the current Mount Zion) and to the east (the Mount of Olives) also overlook the rocky spur.

This spur nevertheless dominates three valleys: the Kidron Valley to the east (which crosses the Judaean Desert to the Dead Sea), the Valley of Hinnom (or Gehenna) to the west, and that of Tyropoeon, which passes through approximately the middle of the present Old City from north to south. The curious word Tyropoeon comes from The Jewish War by the first-century historian Flavius Josephus1 and literally means “Cheesemakers,” but it must in fact be a corrupted form of a lost original Semitic name. Whatever the case, since at least the first century BCE, this third valley has divided the city into eastern and western parts before joining the Kidron Valley at the current Pool of Siloam, a bit north of the latter valley’s junction with the Valley of Hinnom. Still another valley, less known and named Beth Zetha, runs almost in parallel with the Kidron Valley; its starting point is at the famous American Colony Hotel north of the present Old City, and it joins the Kidron Valley at the foot of the northeast end of the Temple’s esplanade. It quite naturally formed the north edge of the esplanade and of the city itself in the Israelite period. This valley carries abundant water in winter, hence the presence in this area of basins like the Pool of Bethesda and the Pool of Israel (Birket Israel). Finally, the western part of the current Old City is divided by the Transverse Valley—also called the Cross Valley—the only one with a clear east-west orientation. It starts from the Citadel (near the Jaffa Gate) and joins the Tyropoeon to the north of the Western Wall (or Wailing Wall). This valley corresponded to the northern limit of the city in the Hasmonean period (see map 3). Some of these valleys are no longer visible today, as they have been partly filled in over time, but the height differences of the past have been measured during archeological digs.2

The main reason for the settlement of a human group on Jerusalem’s site in the Bronze Age doubtless lies in the presence of a fountainhead, known as the Gihon Spring, below the rocky spur. This permitted the development of farming on the valley floor from the earliest era, despite very steep slopes and a very dry climate, in a region at the crossroads of two climatic zones, the Judaean Desert and the Mediterranean coast. The rainfall pattern, typical of a mountainous region, did not guarantee regular showers throughout the year; the rains, often violent and sudden, were concentrated from November to April. Additionally, precipitation was quite unequal from one year to the next, resulting in serious water-supply problems, even though the median rainfall (500 millimeters, or 20 inches, per year) is comparable to that of certain European areas (580 millimeters, or 23 inches, per year in London, for example). Another constraint of the site, the steep slope of the rocky spur with the first settlement area, forced the inhabitants, from the beginning, to build terraces and embankments, on which successive urban constructions were piled atop each other (see map 2). This led to the continuous reuse of materials and foundations of preceding eras and partly explains why it is difficult to find traces of certain strata and thus of certain periods—a recurrent problem for those who wish to write the city’s history.

Map 2. Biblical Jerusalem

The history of ancient Jerusalem, for a long time essentially dependent on biblical sources, has nevertheless been profoundly revised by the archaeological excavations that have been conducted there since the nineteenth century, but also by those at other Middle Eastern sites, which have helped to put into our hands evidence (Moabite or Assyrian, for example) invalidating or confirming certain elements of biblical tales.3 Indeed, at the heart of the historiography of Jerusalem and of ancient Israel in general resides the problem of the historical accuracy of biblical information and of its often conflicting dialogue with the material remains unearthed by archaeological digs.4 This methodological problem arises equally for the postbiblical period—Flavius Josephus’s testimony must similarly be corrected in the light of archaeological data on Judaea in the Hellenistic and Roman eras, for example—but it is particularly acute for the biblical era, in view of the sacred character of the text in the eyes of Jews and Christians, as well as the contemporary political issues around the State of Israel. Modern Israel’s founding fathers indeed considered the biblical tales of the ancient Kingdoms of Israel and Judah as one of the pillars of the new state’s legitimacy, and today the Bible still remains the great founding story of Israeli national identity—hence the particular intensity of the debate on the reigns of David and Solomon, from whom the Israelite and Judaean monarchies ensued. Yet, as we will see, from the point of view of Jerusalem’s urban history, David’s reign seems not to have represented a real break but is, rather, in keeping with the Canaanite occupation of the site. Without necessarily rejecting the testimony of the biblical sources, which can contain useful information if read critically, the historian must be freed from the theological interpretation of history that characterizes the Deuteronomistic corpus, all the biblical books called “historical,” from Joshua to Second Kings.

In antiquity, as in later periods, politics and religion were closely mingled. Without artificially disassociating what should be thought of jointly, we must nevertheless emphasize the strictly political, geostrategic, urban, economic, and social aspects of this history. It is furthermore necessary to grasp the fundamental role, at once social, political, and religious, of the Temple of Jerusalem, a role that escalated from around the tenth century BCE until its destruction in 70 CE (in spite of its destruction and reconstruction during the sixth century BCE) and conferred on the city, little by little, its specificity and its greatness. Alongside the chronology based on the empires that successively dominated the Middle East (Assyria, Babylonia, Persia, Hellenistic kingdoms, Rome) appears a Jewish chronology which for its part describes a “period of the First Temple” (tenth century–586 BCE) and a “period of the Second Temple” (c. 539 BCE–70 CE), interrupted by the Babylonian interval—that is, a chronology centered on the construction and destruction of sanctuaries.

In a manner altogether ordinary for antiquity, Jerusalem’s history is, in fact, punctuated by wars, destruction, and reconstruction: the Assyrian siege of 701 BCE, Babylonian destruction of 586 BCE, punitive expedition and profanation of the Temple by Antiochus IV in 167 BCE, capture by Antiochus VII in 134–133 BCE, capture by Pompey in 63 BCE, capture by Herod in 37 BCE, and destruction by the Romans in 70 CE, to mention only the most prominent events of the city’s ancient history. Constantly, in the sources relating to these episodes, the question of the sanctuary menaced, profaned, or saved in extremis appears in the foreground. The alternation of destructions and reconstructions concerns above all the walls of the city, indispensable protection and guarantee of independence. Once again, looking past the episodes of destruction, we observe throughout the first millennium BCE a crescendo, up to the apogee represented by the construction of the third wall by Herod Agrippa I in the first century CE, followed by the radical destruction in 70 (see map 3). As we will see, the defeat in 70 followed by the foundation of the Roman colony Aelia Capitolina in the second century CE represents the deepest and most enduring rupture that ancient Jerusalem experienced. But we must first of all return to the modest beginnings of the little urban cluster that would become the thrice-holy city.

THE BRONZE AGE: A FORTRESS AROUND A SPRING

The very first proof of the presence of even slightly sedentary humans, dating back to the end of the fourth millennium BCE, is hardly impressive: it was at best an unfortified farming village, situated near the Gihon Spring. Graves began to appear at that time on the southwest slope of the Mount of Olives, the eastern slope of the Kidron Valley (see map 2). They continued to be used, it appears, during the phase when the site was abandoned in the middle of the third millennium BCE. This abandonment isn’t unique to Jerusalem, as the surface excavations conducted in the West Bank by Israel Finkelstein, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University, revealed the existence of recurrent cycles of occupation in the “highlands” (Judaea-Samaria, the current West Bank) from the fourth millennium until the beginning of the Iron Age, in the twelfth century. According to the archaeologist’s observations, the same sites were inhabited, abandoned, and then reoccupied on three occasions: around 3000, around 1800, and finally around 1200.5 Jerusalem fits well in this general pattern, but during the second occupation cycle, in the Middle Bronze Age, it had already emerged as a regional power, despite its unusual character. Indeed, the remains of a fortress with imposing walls, dating to the eighteenth century BCE, have been uncovered, notably near the Gihon Spring; the perimeter wall must have been around three meters (ten feet) wide. Comparable fortifications have been identified at Tel Rumeida, now part of Hebron, and at Tell Balata, ancient Shechem (modern-day Nablus).

Jerusalem thus very probably represented one of the principal city-states that developed during the second urbanization phase in Canaan. This hypothesis is corroborated by the mention of Jerusalem in an execration text (that is, a text consisting of a curse) discovered on a nineteenth-century BCE Egyptian figurine, as well as in eighteenth-century BCE Egyptian documents. Jerusalem is designated in these as R-Sh-L-M-M, which should perhaps be pronounced as Rushalimum, and two names of chiefs are associated with it, Shas’an and Y’qar’am. The statuette is broken, which symbolically represents the desire to break the city’s political resistance in the face of Egyptian power, in the framework of a quasi-magical performative rite.

The hydraulic system might equally constitute a sign of Jerusalem’s development at this period. According to the archaeologist Ronny Reich, who brought to light the existence of a tower next to the Gihon Spring, the water-supply structure known as Warren’s Shaft (named for the archaeologist who discovered it in the nineteenth century) dates at least in part to this era, and not to the tenth century BCE, as presumed by Yigal Shiloh, who excavated the City of David in the 1980s (see map 2). Also according to Reich, there was a similar water-supply structure inside Gezer, an important city-state on the coastal plain, in the same period. The importance of these constructions indirectly testifies to the demographic importance of the city, because these projects required the ability to draw on a substantial workforce. Finally, one last indication of Jerusalem’s development in the eighteenth century BCE lies in the presence of decorated bone plaques, probably from finely worked furniture or boxes.6

Following biblical chronology, and provided that one equates the Salem of Genesis 14:18 with Jerusalem, the latter was governed in the eighteenth century BCE by a king named Melchizedek (“King of righteousness” or “My king is justice”), a priest of God Most High, to whom Abraham gave “one-tenth of everything.”7 Genesis was likely redacted very late (sixth century BCE or after), and its historicity is strongly subject to caution, but it remains significant that this text depicts a king at Jerusalem at such an early stage. Perhaps this is the echo of an earlier period, in the fourteenth century BCE, when we know from a reliable source, thanks to Egyptian evidence, that a king reigned at Jerusalem.

But between the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries BCE, we observe first and foremost a phase of decline, again characteristic of the region’s highlands as a whole throughout the Late Bronze Age (1550–1200 BCE). The settlements near Jerusalem were depopulated, and Jerusalem itself also seems to have declined. Moreover, we know that at the end of the sixteenth century BCE, Canaan fell into the orbit of the Egyptian Empire. The Canaanite city-states, governed by kinglets, retained a limited autonomy under strict Egyptian control, exercised through governors installed at Gaza and Bet She’an. This was the time of the Eighteenth Dynasty.

FOURTEENTH CENTURY BCE: THE CAPITAL OF KING ABDI-HEBA, UNDER EGYPTIAN CONTROL

A chance archaeological discovery in Egypt, at El Amarna (the capital of the pharaoh Akhenaton, considered a precursor of monotheistic religions), brought to light evidence unexpectedly related to fourteenth-century BCE Jerusalem, while excavations in that city itself have found hardly any vestiges of the era besides a few shards. There was nothing from Jerusalem itself, therefore, to suggest that it was the residence of a local governor or kinglet. However, the diplomatic correspondence found at El Amarna is definite: of the 382 inventoried letters, six or even seven tablets were sent by the king of Jerusalem Abdi-Heba (or Abdi-Hepa), “Servant of Heba” (a Hurrian goddess); two other tablets, sent by a sovereign named Shuwardata, in turn invoke Jerusalem, called Urushalim, “The city founded by Shalim,” a Canaanite divinity.

The content of these letters, written in Akkadian by a scribe of “Syrian” origin, reveals that Abdi-Heba must have been educated at the Egyptian court, where, like other Canaanite princes, he was likely sent as a hostage. It was the pharaoh himself who named Abdi-Heba the king of Jerusalem, which seems to have been a city of modest size then. An Egyptian garrison of probably fifty men was stationed there, meant to protect the city against attacks by the Habiru (or ‘Apiru), more or less nomadic groups that sometimes allowed themselves to be recruited as mercenaries and sometimes gave themselves up to pillaging herds (let us recall in passing that the theory of an assimilati...