eBook - ePub

Educating the Enemy

Teaching Nazis and Mexicans in the Cold War Borderlands

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Compares the privileged educational experience offered to the children of relocated Nazi scientists in Texas with the educational disadvantages faced by Mexican American students living in the same city.

Educating the Enemy begins with the 144 children of Nazi scientists who moved to El Paso, Texas, in 1946 as part of the military program called Operation Paperclip. These German children were bused daily from a military outpost to four El Paso public schools. Though born into a fascist enemy nation, the German children were quickly integrated into the schools and, by proxy, American society. Their rapid assimilation offered evidence that American public schools played a vital role in ensuring the victory of democracy over fascism.

Jonna Perrillo not only tells this fascinating story of Cold War educational policy, but she draws an important contrast with another, much more numerous population of children in the El Paso public schools: Mexican Americans. Like everywhere else in the Southwest, Mexican American children in El Paso were segregated into "Mexican" schools, where the children received a vastly different educational experience. Not only were they penalized for speaking Spanish—the only language all but a few spoke due to segregation—they were tracked for low-wage and low-prestige careers, with limited opportunities for economic success. Educating the Enemy charts what two groups of children—one that might have been considered the enemy, the other that was treated as such—reveal about the ways political assimilation has been treated by schools as an easier, more viable project than racial or ethnic assimilation.

Listen to an interview with the author here and read an interview in Time and a piece based on the book in the Boston Review.

Educating the Enemy begins with the 144 children of Nazi scientists who moved to El Paso, Texas, in 1946 as part of the military program called Operation Paperclip. These German children were bused daily from a military outpost to four El Paso public schools. Though born into a fascist enemy nation, the German children were quickly integrated into the schools and, by proxy, American society. Their rapid assimilation offered evidence that American public schools played a vital role in ensuring the victory of democracy over fascism.

Jonna Perrillo not only tells this fascinating story of Cold War educational policy, but she draws an important contrast with another, much more numerous population of children in the El Paso public schools: Mexican Americans. Like everywhere else in the Southwest, Mexican American children in El Paso were segregated into "Mexican" schools, where the children received a vastly different educational experience. Not only were they penalized for speaking Spanish—the only language all but a few spoke due to segregation—they were tracked for low-wage and low-prestige careers, with limited opportunities for economic success. Educating the Enemy charts what two groups of children—one that might have been considered the enemy, the other that was treated as such—reveal about the ways political assimilation has been treated by schools as an easier, more viable project than racial or ethnic assimilation.

Listen to an interview with the author here and read an interview in Time and a piece based on the book in the Boston Review.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Educating the Enemy by Jonna Perrillo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 : The Fight for Civilization

On a cold December night in 1946, fifteen towheaded German children and their mothers boarded the USNS Goethals and set sail from Bremerhaven, Germany for Hoboken, New Jersey. They would then board a train in New York City and cross the country to their new home in El Paso, Texas, where they would live at one of the nation’s largest army bases, Fort Bliss, in retired hospital barracks surrounded by barbed wire. Their journey went unrecorded in official immigration documents; they were, as then-child Uwe Hueter would later term it, “nonexistent immigrants.”1 But they were noticed nonetheless by the American religious leaders, scientists, and State Department staff who protested their entry. In 1945, in the final weeks of World War II, the U.S. Department of War had organized the rapid recruitment of Nazi scientists while the Soviets did the same. As one war ended, another began. The 118 scientists who were brought to Fort Bliss in late 1945 had built the Third Reich’s most dangerous weapon, the V-2 missile. They were the most significant cohort in the controversial military campaign Operation Paperclip. Now, as the first of the scientists’ families sailed aboard the Goethals, the children spent an evening singing for the American naval officers who were their fellow passengers. The concert included a selection of predictable if suitable German children’s and Christmas songs as well as “O alte Burschenherrlichkeit,” a nineteenth-century fraternity hymn that both Nazis and Catholics had heralded for its messages about brotherhood. It closed with “The Star Spangled Banner,” sung in English, a language the children did not know. The event captured some of the performative nature of and moral ambiguity between fascism and postwar Americans’ strident efforts at antifascism. It also highlighted, in addition to strained attempts at camaraderie and good faith, the centrality of children as political actors and subjects early in the Cold War. The performance “was the highlight of the whole voyage,” the ship newsletter recorded, a period of relief in a trip that had been “grey and rough” and had invited much seasickness.2 Much like the children themselves, the concert offered a seeming respite from a morally complicated affair.

The Goethals performance was the first of many such moments Americans would entertain and invite of the Paperclip children, one of many times in which the children would be made into emblems of unity and the allure of Americanization. The children played other roles in a complex narrative of Nazi repentance and American absolution as well. More intimately, they served as public representations of their families’ reformation and assimilation. From the time the scientists were identified for “exploitation,” as the War Department referred to the arrangement, American military officials prioritized the Paperclip wives’ and children’s comfort and security in Germany while they awaited relocation. When the families began to reunite with the scientists, newspapers from Albuquerque to El Paso celebrated the occasion, describing the men waiting at the train platform as seeming “more like excited schoolboys than highly-trained men with doctor’s degrees.”3 Referred to always by the press as “the German scientists,” the V-2 men appeared for the first time as husbands and fathers, making them immediately seem more sociable, more approachable, and perhaps even potentially American. To the scientists, too, their children represented more than just their closest relations. In December 1946 Time magazine reported that the scientists “have been told they may have a chance to become U.S. citizens. The fact that the U.S. is bringing their families to them seems to be a kind of guarantee that that is a promise.”4 For Americans and Germans alike, the Paperclip children signified both sides’ commitment to the operation and to the remaking of Nazi scientists into model American citizens.

Finally, the children testified to the power of American democracy and the most important institution in the shaping of democratic citizens: American public schools. While their fathers designed missiles for the army, the children were bussed daily by military police to El Paso schools. In school they had far more interaction with American civilians than did their parents; this socialization, coupled with the curriculum, was designed to produce an education in democracy. While there were many, often conflicting philosophies of what was meant by a democratic education before World War II, El Paso schools fell victim to some of the least interesting interpretations. Theirs was not the kind of education for democracy promoted by the groundbreaking reading theoretician Louise Rosenblatt, who argued in 1938 for education that promoted self-reflection and “liber[ation] from the provincialism of [the student’s] particular family, community, or even national background.” Nor was it the democratic education of the social scientist and teacher educator Harold Rugg, who encouraged examination of how “the social machinery of American life is badly jammed,” because of the “undue control of wealth, communication, and government by a minority of the people” who practiced “uncontrolled individualism.” Instead, El Paso students practiced democracy through routine and recognition: through singing patriotic songs; memorizing famous speeches; making murals, friezes, and dioramas of select historical events; and by writing plays and speeches about Anglo men. They carved battle scenes out of soap, made “Indian” jewelry out of macaroni, and reenacted the signing of the constitution.5 It was a pedagogy of confirmation rather than investigation of the social status quo; in various ways, it taught students that democracy was inextricably bound to a history of white privilege and supremacy. Like the concert on the Goethals, much of the education in democracy children received in El Paso schools was about behavior or feeling more than thought, even as such feelings vastly misrepresented the moment or the students at hand.

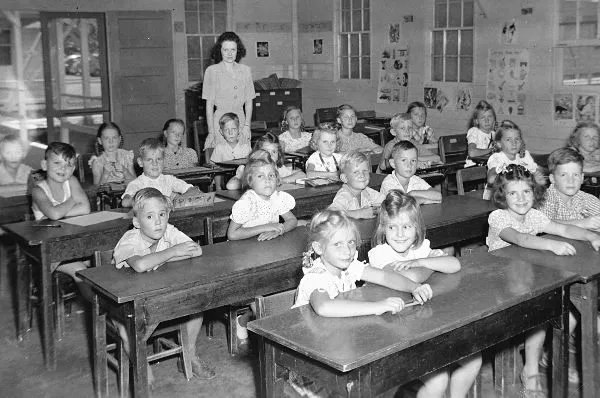

It was through this lens that in August 1947 a local reporter visited Fort Bliss, where the Paperclip children were attending summer school in a makeshift schoolroom for which their parents paid $2.25 a week. Three El Paso teachers taught the classes in the hopes of quickly improving the children’s English proficiency. When asked by the reporter what she liked best about American schooling, seven-year-old Karin Friedrich responded, “I like to say the Pledge of Allegiance better than anything.” In the four months she had lived in El Paso, Karin had learned more than prayers and the pledge: she had come to understand their importance as rituals and enactments of American citizenship. She was not alone. When teacher Nettie Bea Bryant asked the class for a volunteer to hold the flag during the pledge, “arms waggled from every desk in the room”; when the students recited it, the “casual listener[s] would not know the group of voices was that of German children.”6 The news report on the Paperclip children, one of several that summer that highlighted the children’s eager Americanization, served as a public-relations boost for American schooling as much as for the students. Children who had not just been born into Nazism but had profited from their fathers’ service to the Third Reich—first in Germany and then in the opportunity to escape their homeland—reflected back to Americans the virtues of a democratic education. If enemy children could be brought into the fold, seemingly anyone could.

Historians and journalists have sought to understand the story of Operation Paperclip for its extraordinary if problematic tale and for what it reveals about Cold War national-security anxieties.7 Yet, the Paperclip children offer a glimpse into entire other aspects of postwar American political and social culture, including public schooling in the transition to the Cold War, the youth who were enfranchised and disenfranchised by schools, and the relationship between public schools and citizenship in the most literal sense. Early Cold War schools framed democratic education as antifascist and anticommunist education. In many ways the Paperclip children offered a perfect study; they, better than anyone, could prove the power of democracy and public schooling over fascism. A group of 144 children in a school system that served over 32,000 students, they lived in El Paso for just three years before their families moved to Huntsville, Alabama in 1950, where their fathers would build the American space program.8 Nevertheless, they illuminate far more about the role of schooling as a central institution for framing, disseminating, and upholding dominant American political beliefs than numbers might suggest. In coming to the United States, the Paperclip children traded participation in one democratization project—the denazification of postwar German schools—for another: their own induction into American ones. They arrived in El Paso as foreigners, not just children of a recent enemy nation but more specifically the progeny of Nazi servants. When the Paperclip families relocated to Huntsville, they left practiced in many of the most important tenets and expressions of American citizenship, prepared for assimilating into white American society in the Jim Crow south.9 In 1955, less than ten years after their controversial and contentious invitation to live in the United States, almost all of the Paperclip children and their parents would become American citizens.

That their initiation to the United States and American schooling first took place in the border city of El Paso is critical. If the scientists and, by proxy, their children were unexpected allies, the Mexican American students who comprised over 60 percent of the city’s student body were characterized by some local educators as a “natural resource” at a time when American interests in Latin America and hemispheric relations felt more urgent than ever.10 To win the Cold War, the United States needed the help of neighborly alliances. And yet, just like those in the rest of the southwest and Texas, shockingly few of El Paso’s Mexican-heritage students were treated as resources; the great majority were segregated in “Mexican” schools on the city’s South Side, most in a neighborhood called El Segundo Barrio. There they faced overcrowded classrooms, partial school days to accommodate students in shifts, and an almost entirely Anglo teaching force, few of whom spoke the student’s first language of Spanish. Even though their parents petitioned for better schools, Mexican American students were assigned to educational situations that no Anglo students in the city endured. They, far more than the Paperclip students, who were assigned to the city’s “American” or Anglo schools, were marginalized and considered foreigners—and, this book illuminates, enemies, in a nation that perpetually treated democracy and security as a reward for whiteness.

Much of the treatment of Mexican students relied on popular interpretations of them and Mexican Americans more generally as reluctant democrats and citizens. Harold Davis, the director of the education division of the Office of Inter-American Affairs, a wartime federal agency focused on preventing the proliferation of first Nazism and then communism in Latin America, offers a case in point. Davis oversaw cultural and education programs designed specifically to improve relations between Americans and Latin Americans, yet even he believed that the “attitudes on the part of Spanish-speaking groups” needed to be changed before their children could be effectively taught. Specifically, Davis identified “feelings of hostility growing out of the Mexican War, the Mexican Revolution and attendant border disorders” that led “Spanish-speaking groups to retire within themselves—psychologically and culturally.” His political interpretation of the cause of Mexican Americans’ inwardness invoked long-standing fears of Mexicans as anarchists and even potential fascists. This was different from the view of teachers, who saw Mexican children as poorly socialized and neglected at home, but they and Davis shared a sense that Mexican students were ill-suited to democratic schools and society. Just as some Americans believed that German children could be politically reformed through schooling, teachers hoped, often with less conviction, that schools could socialize Mexican American children and that their “cultural resistance [could] be overcome partly through the schools.”11 Teachers’ faith in the power of schooling and their attachment to interpretations of the characteristics each group of children possessed—the Germans idealistic and social, the Mexicans diffident and reclusive—shaped their teaching methods and curriculum.

The Paperclip children therefore offer a new vantage point on a larger story of race and privilege in American history and the vital role that schools played in making and reinforcing both. Looking back on his early days in El Paso, former Paperclip child Walter Tschinkel recalls that “we German kids, we were admired for being smart. Not all of us were. But . . . almost without exception, we did well in school. . . . So we were branded as smart.”12 The Paperclip children’s privileged status as the children of scientists and as Anglos in a border city informed both their parents’ and their teachers’ expectations that they would contribute and succeed. Americans’ and Germans’ confidence in the children’s aptitude shaped their academic performances and what the children would encounter and experience in school. Certainly familial dynamics could differ from one child to another. Hertha Heller remembers that her mother “was always very positioned on us having opportunities, because [she] lived through those years where things were very controlled and [she] didn’t have opportunities.”13 By contrast, Regine Woerdemann echoed the sentiments of other women in remembering that “there [were] no big expectations on my father’s part as to what I would be doing” in school or for a career, a marked contrast to her brother’s experience.14 Paperclip girls, like American girls, were less frequently expected to attend college or to prepare to pursue significant careers, though many did. Still, the belief that the children were enthusiastic, optimistic, and disciplined, doing their best at what was expected of them for their age, helped Anglo Americans to see Paperclip children as much like their own. “Dressed like any American child . . . [girls] with their hair in long pigtails,” even the children’s heavily accented English sounded American.15

Figure 1.1: Young Paperclip children in summer school at Fort Bliss, preparing for the fall in El Paso elementary schools. Courtesy of Walter Tschinkel.

This book, then, is about the Paperclip children; but it is also about the idea of the Paperclip children, and what that idea tells us about American social thought in the earliest days of the Cold War. Most of the children were too young to hold political affiliations of their own or to have joined Hitler Youth programs in Germany. Of the 144 Paperclip children who arrived in El Paso between 1946 and 1948, only six were born before 1935 and thus old enough to have been involved with Hitler Youth. In fact, the majority were born after 1940, making them too young to have even experienced formal education in Germany.16 Still, in ways that were shared by other economically privileged white children, they were consistently treated by American educators and journalists as political agents in a cold war that was fought in no small part through images of and attitudes toward children. They and their Mexican American peers illuminate what occurs when racialized and politicized images of foreign (or fore...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The Fight for Civilization

- 2. Something New in the Territory

- 3. At Home on the Range

- 4. The Promise and Peril of Bilingualism

- 5. Devoted to the Child

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index