eBook - ePub

Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design

An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms

- 586 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design

An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms

About this book

Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design: An Encyclopedia of Mechanisms, Second Edition compiles hundreds of game mechanisms, organized by category. The book can be read cover to cover and used as a reference to solve a specific design problem or for inspiration and research on new designs. This second edition collects even more mechanisms, expands on and updates existing entries, and includes color images. Building Blocks is a great starting point for new designers, a handy guidebook for the experienced, and an ideal classroom reference.

Each Game Mechanisms Entry Contains:

- The definition of the mechanism

- An explanatory diagram of the mechanism

- Discussion of how the mechanism is used in successful games

- Considerations for implementing the mechanism in new designs

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design by Geoffrey Engelstein,Isaac Shalev in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Computer Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Game Structure

DOI: 10.1201/9781003179184-1

The first choice that designers make about a game is the game’s basic structure. Who wins? Who loses? What is the overall scope of the game experience? Will it be just one game or perhaps a series of hands? Maybe, the game will encompass many scenarios, with game-state information persisting from play to play? The last 20 years of tabletop gaming have brought us enormous innovation in game structures, with no signs of slowing down.

Consideration of game structure raises the question of what it means to actually play the game. In a cooperative game, is the discussion among the players over which action to take the core of the gameplay, or is it the active player executing the action that is core? In games which limit communication, is the main gameplay overcoming the communication limits or solving the puzzle that the game presents? Designers need to be sensitive to participation issues in team games as well, because the game itself may force most of the action over to one teammate at the expense of another, which impacts player experience.

An increasingly popular trend is the inclusion of multiple game structures in the same box. For example, Mage Knight includes ways to play competitively, cooperatively, and solo. This extends the potential audience for the game.

In this chapter, we’ll consider both the traditional structures like competitive and team games, as well as the latest ideas in scenario-based, legacy, and consumable games.

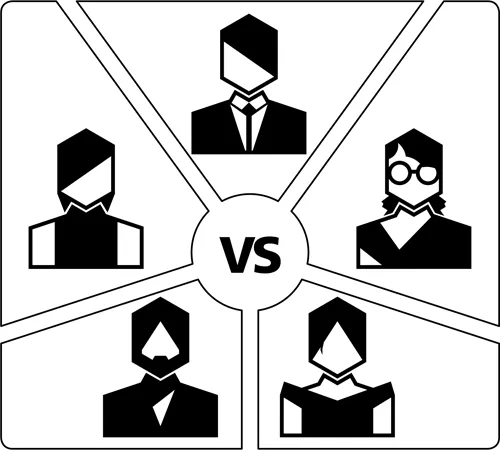

STR-01 Competitive Games

Description

A game with two or more players and a single winner.

Discussion

This is the most familiar game structure, the one we encounter as children in games like Candyland and Snakes & Ladders. Competitive games still make up the large majority of the market for tabletop games. They typically offer a symmetry of expectations: putting aside the impacts of unusual luck and skill, each player begins the game with a roughly equivalent chance of victory. When this promise is broken, the game is considered imbalanced and may even be tagged with the label “broken.” As we’ll discuss later (see “Variable Player Powers” in this chapter and “Variable Setup” in Chapter 6), players may have perfectly symmetric factions and starting conditions or highly asymmetric ones. But, in both cases, it’s important that the game offers roughly even chances of victory to each player (Illustration 1.1).

In many games, there is an asymmetry that in-game balancing alone can’t solve, like the first-mover advantage in chess or the service advantage in tennis. Competitive games often balance these advantages through meta-structures, like tournaments, that offer each player an equal number of chances to play from the advantaged position. In multiplayer games, this may be less practical. Instead, players may be offered other opportunities to balance any perceived or actual inequities, like the bidding in Bridge, betting in Poker, or the early alliances in Diplomacy.

The promise of balance in a competitive game gives rise to several related issues, like methods for determining victory and breaking ties. Tie-breaking (RES-18), in particular, is interesting because crowning a winner in a competitive game depends upon the game storing information that allows players to determine who played the better game. For many games, this information may not be available. Once we have to look beyond who scored the most victory points or who crossed some finish line first, there may not be relevant game-state information that could allow us to reasonably determine which of the tied players played best. And yet, in competitive games, many players disdain a game that ends in shared victory. Experience-oriented designers should consider that players tend to recall how a game ended more than the rest of the play experience, and hence the designers should seek to avoid an indecisive conclusion.

Sample Games

- Acquire (Sackson, 1964)

- Candyland (Abbot, 1949)

- Chess (Unknown, ∼1200)

- Diplomacy (Calhamer, 1959)

- Senet (Unknown, ∼2600 bce)

- Snakes & Ladders (Unknown, ∼200 bce)

STR-02 Cooperative Games

Description

Players coordinate their actions to achieve a common win condition or conditions. Players all win or lose the game together.

Discussion

Quite a few games call for cooperative play among players, including team games, one-vs.-many games, role-playing games, and games with secret traitors. These can be viewed as belonging to a hierarchical category of cooperative games. Some might even include solo games in this group. For our purposes, we’ll treat each of these as separate categories and limit ourselves here to “pure” cooperative games in which all players play on one side and win or lose as a group.

Since 2008, when Matt Leacock released Pandemic, the genre of cooperative tabletop games has exploded. Earlier games like Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective, Arkham Horror, and Lord of the Rings laid a foundation and enjoy enduring popularity, but Leacock started a wave of innovation in cooperative gaming that continues to reshape modern gaming a decade and more later.

Cooperative gaming is accessible because it lowers barriers to entry for a game. Disparities in skill level can often make a competitive game a sour experience both for the expert and the newcomer. Complex competitive games can be intimidating to new players. Being coached by your opponent in such a game introduces some negative play dynamics because of the misaligned incentives of helping your opponent. The power imbalance between the players can also create awkward social dynamics. Cooperative games put players on the same team and foster comradery while allowing experienced players to help teach both the mechanics and strategy of the game, without facing conflicting incentives. For many new players, cooperative games are not only a gateway into gaming but a mainstay of their ongoing consumption of games.

Cooperative games can broadly be placed into two categories: those with artificial intelligence (AI) and those without. Cooperative games with an AI, like Sentinels of the Multiverse and Mice and Mystics, feature an opponent or opponents who behave according to a simple artificial intelligence, encoded by the designer. In Sentinels, the AI is driven by a deck of cards that governs the actions of the enemy villains and the players they will target. Mice has a simple algorithm that players use to control the play of enemy figures.

Non-AI games like Hanabi, the revolutionary Antoine Bauza title, and Mysterium present players with a puzzle to solve and limitations on time, resources, and interaction that players must contend with. However, these games have no villain or opposing force that drives the action and actively confronts the players.

Another consideration for the designer of cooperative games is keeping the difficulty consistent while scaling with a number of players. If each player has a set number of actions they may perform on their turn (as in Pandemic, for example), four players will have twice as many actions per round as two players. While there are many techniques, a very common design pattern is alternating between a player taking a turn and the game taking a turn—basically alternating “Good thing” (player actions) with “Bad thing” (game actions). This scales naturally as the number of players increases.

Another distinction between different kinds of cooperative games is whether each player retains agency over their in-game resources, actions, and choices or they seek consensus for all decisions, even if they nominally represent separate in-game characters. We might call the former game a partnership game and the latter a collaborative one. In general, cooperative games will tend to be played collaboratively unless the rules specifically and substantially impede this collaboration and force players to make independent decisions rather than build consensus. Examples i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Endorsements

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Author Bio

- Introduction

- Introduction to the Second Edition

- 1 Game Structure

- 2 Turn Order and Structure

- 3 Actions

- 4 Resolution

- 5 Game End and Victory

- 6 Uncertainty

- 7 Economics

- 8 Auctions

- 9 Worker Placement

- 10 Movement

- 11 Area Control

- 12 Set Collection

- 13 Card Mechanisms

- Game Index

- Index