- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

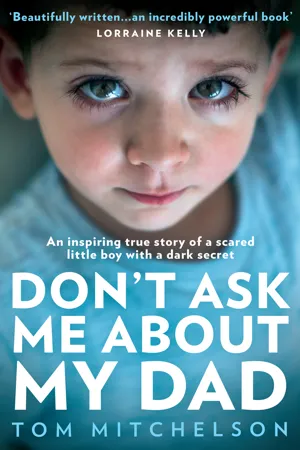

Yes, you can access Don't Ask Me About My Dad by Tom Mitchelson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

2017, Portugal

My dad was dying. Death was in the air and the pallor of his skin. I could feel it in my bones. But I didn’t fear it. In fact, I wanted to press fast forward and skip to the last scene. I wasn’t going to mourn him. I knew that. I wondered if I’d find myself missing him. I wasn’t sure. I suspected I would breathe a sigh of relief. I wanted our forty-year-old relationship to be over.

His trolley was pushed up against the wall in the corridor, along with twenty or so others. The yellowish light flickered down on the blue linoleum floor and the smell of disinfectant and take-away Portuguese pastries pervaded the air. From inside one of the little consulting rooms nearby, two deeply wrinkled women wailed with sadness and, moments before, as I had passed one of the lined-up trolleys, an elderly man, wild eyes shot through with fear, had reached out from the bed and grabbed the sleeve of my jacket, pleading with me, ‘Ajuda-me! Ajuda-me!’ Help me, help me.

My dad lay feebly on the bed but some of the colour had returned to his cheeks. I had only been away fifteen minutes – I had been trying to find somewhere to leave his bag – but his relief at seeing me was obvious. He’d been put on a drip and told he would be kept in overnight. He just wanted the surgeons to fix him up so he could get back to his flat and drink gin and tonics.

‘Do you have my keys and wallet? I can’t find them,’ he said.

‘Yes, they’re in your bag in a locker and the nurse knows which locker it is.’

‘What about my hairbrush?’

I surveyed the anarchic scene around us once more as the crying from the old women reached a crescendo. ‘I wouldn’t worry about it, to be honest.’

He nodded. He was anxious about making his flight back to the UK. He had a hospital appointment in two days’ time and now he was asking me to go in search of a doctor to find out if he’d be able to travel. I knew that no one would be able to make him any such promise, but to ease his worries I agreed.

Earlier that day I had visited him in his tiny, filthy studio apartment in a small Portuguese town called Sesimbra. It was obvious he was seriously ill. He could barely stand up. I called the taxi driver, Nuno, the fifty-year-old man who looked like a washed-up Julio Iglesias. My dad had been using him as a personal chauffeur to ferry him to and from the shop, and we got him to drive us to the nearest hospital.

My dad was compos mentis and chatted happily in the car, making jokes with Nuno, who spoke English with the tortured formality of a mistranslated instruction manual.

‘St Bernardo is a proficient medical centre and I believe you will receive care that most people would consider satisfactory,’ he told us with a less than comforting grin.

My dad had managed to keep his hair during the rounds of chemotherapy, and although he had lost weight he looked good for his seventy-two years. His false teeth gave him a full smile and his blue eyes were sharp and clear. The only physical sign that hinted at the chaos in his life was the sight of around thirty long bristles protruding from his chin and neck that he’d missed while shaving.

He’d moved to Portugal just as his treatment in the UK had ended, and now that he was living abroad, the bladder cancer had returned. I had to carry him from the car, which was surprisingly easy, but it was still difficult to manoeuvre him from the car seat.

Nuno was now standing beside me, and for a moment I allowed myself to be distracted from the grave situation by what he was wearing. A crisp pink shirt under a tight bright-red V-neck jumper, extremely skinny stone-washed jeans and brown suede shoes, which I noticed were different shades of brown.

‘Now I have delivered you to the aforementioned place, I can delay myself until I receive information that you can impart to me at a time when you choose,’ Nuno said, and then wandered back in the direction of his car.

It was only when I had planted my dad on the beige plastic A&E seat that I noticed his blood was all over my shirt and there were splodges down his trousers. I showed his European health card to the woman behind the desk, paid a €16 fee and then we sat and waited for hours and hours. They brought him a wheelchair and I was able to take him for his frequent toilet visits.

Each time I had to lift him onto the seat and then stand outside, guarding the unlocked door. I could hear his agonised shrieks as he passed urine. Rather than feeling sympathy for his pain, I thought what a coward he was. Why couldn’t he swallow his discomfort and desperation? I bet his great hero John Wayne didn’t whinge and flail as he died from cancer; more likely he winced and bit his lip and said, ‘The big ole C ain’t beat me yet.’

Once he’d finished, I’d go back in and help him pull his trousers up, get him back into the wheelchair and then wipe away the blood from the floor with the cheap loo roll you always get in hospitals.

My dad was lost and scared and looked to me for everything. He was a small child again, stripped of his compulsion to control things, and longing for me to rescue him. He was totally absorbed in his own plight and it made me seethe with anger.

He was nothing in this hospital. Just another miserable, toothless old man waiting in line to die, alongside the very people he had always scorned – the helpless. I stayed with him for hours, fetching food and water, talking to him, calming him down and speaking with the nurses in pidgin Portuguese to get information about when he might be treated.

Why was I here after all he had done? Growing up with him was like being in my own war zone, living in perpetual fear of when the bombs would fall. He physically abused and terrified my mother, the only person I had to hold me. He made me cower in a toy store at the age of nine, when we returned a faulty toy, the manager refused a refund and my dad became so aggressive that the manager pushed a panic alarm and called the police. He smashed up the furniture in our home; he screamed with volcanic rage in my eight-year-old face. His criminal viciousness was his defining characteristic. He made my body shake every day of my childhood.

While he committed unspeakable acts downstairs, I paced up and down in my bedroom, pressing my sweaty hands hard together, while my rising panic meant I talked out loud to myself to try to keep calm. When his temper flared a whole world of trouble came crashing down, and yet why was I here after all he had done?

He made me susceptible to a molester, he gave me diarrhoea throughout my primary school years and he made me suspicious of everyone I met. I doubted their motivations and I doubted their kind souls.

He taught me that the world was something to be wary of and made me unsure of my own instincts. I was terrified of becoming him, and in moments I could feel I might. He still lives within me grimly like some battered demon sprite. And I’m fearful of his shadow. The rage, and his blood. There are some moments when he arrives and I want to tear up the whole world with my bare hands, and all I really want is love. I want him away now. Please. Just go.

There was no one else in his life prepared to stay with him in these final days. Nuno, a man he paid, and me, his son, who loved him but hated him too. He was my friend and he was my foe. I jumped to his defence so many times, yet I could have killed him myself. I was bound to him in a way I didn’t understand back then.

My first ever memory was of me and him. I was three and pedalling my miniature police car on the way home. My legs worked hard to propel me along, and it was a lot of work for the limited speed. There was a blue siren on the front above the steering wheel and an orange telephone on the dashboard. My dad was walking behind and suggested I call my mum to let her know we’d be home shortly. I held the receiver to my ear and made up a conversation. I was happy and secure. If I saw that scene today from across the street, it would make me smile. A father and son together. Him keeping a watchful eye, making sure I kept to the pavement, joking with me and pointing me in the direction home.

The man on the hospital bed right now was that man too, but I couldn’t separate the brute from him. The only thing I was certain of was that I had to be there to see this thing through to the end. I had to be a good son because otherwise what was left?

I could have had a more straightforward life, and my sisters too. What he did to us weighed heavily on me and I couldn’t bear to admit the crushing effect it had had. Even now I don’t want to accept that is the case, because if I do the sadness won’t wash away.

I was conditioned by him. I thought this was what sons did, unquestioning and loyal. Here I was, serving my dues because I thought I owed it to him. I never realised I owed him nothing. I didn’t have to give him the time of day, and had I realised that, I could have been free.

I knew what he had done was wrong but I didn’t feel it in my heart. I couldn’t allow myself to. So I never faced it. I had to believe in the bond between him and me because I felt it. I knew it existed, but it was so contorted with resentment I could neither break nor accept it, so we remained shackled like two quarrelling convicts in a chain gang.

The man in front of me now, lying on a trolley pushed up against a wall, had caused me so much damage, but he was my father. And even nearing forty I still needed him. I needed to extract what good there was and try to forget about the rest. And, although I couldn’t admit it to myself, I wanted to be free of him, his solipsism and the chaos he wrought.

But instead I kissed him on the forehead and went in search of a doctor.

Chapter 2

There were eyes on us wherever we went. And a lot of questions. I can still feel the furtive gaze of rubbery-faced shop owners and see whiskery old women waving from shuttered windows. There were affable approaches from smiling waiters, and sun-kissed girls would run out from stone houses to ask us where we were from. I was four years old. I would look up to see scruffy, thin leather belts around old men’s waists while having my wavy blond hair ruffled. I hated that, as well as the rough fingers pinching my cheeks, wobbling them affectionately.

It was 1981. My dad quit his job as a newsreader at Radio Orwell, sold our house for £11,000 and led his family out of Essex to the wilds of post-revolutionary Portugal, all in search of a dream: to buy land, set up a campsite and ignite a tourist trade on the south-west coast. We drew attention partly because foreigners were rare in that part of the world back then, but mainly because I had twelve-year-old identical triplet sisters, Emma, Kate and Victoria, who were often dressed in the same clothes because it saved time when shopping, avoiding sartorial arguments.

On closer inspection, the friendly locals would see that my mum had only one hand. This added to the circus-like interest we received. And then there was my dad, side-parted black hair, a full moustache and Buddy Holly glasses. Tall, slim, with a sprinkling of Portuguese. He was quite an imposing man, seeming bigger than he was, although he wasn’t small. He was the type of person that made people want to be liked by him.

Once we’d got to know whatever new friends had approached us, we’d clamber aboard our bright orange Volkswagen campervan and drive off down the dusty road, with our trailer carrying all our worldly belongings banging along behind.

The campervan was to become a source of dark obsession for my dad, but I loved having it. There was a Formica pull-out table, a spongy mattress bed-seat, a kitchenette and floral curtains, which required about four or five hard yanks to pull them along the white plastic cord. You could be at home while on the road. My parents would fill a kettle with the dribble of water that came from the shaky stainless-steel tap, heat it up on a gas hob and drink a cup of tea while I’d be playing on the rough upholstery of the built-in seat.

The afternoon we left our small semi-detached house just outside Colchester, I remember only two things. The new house owners arriving as we were leaving, hovering around like customers waiting for a table in a restaurant, and burying my face in the soft cotton of my Winnie-the-Pooh pillow to stifle my tears.

A few hours after we loaded our van onto the ferry at Plymouth we sailed into the Bay of Biscay, where giant Atlantic waves crashed into the boat, wind screamed throughout the cabins and we were flung from wall to wall. ‘It’s just like The Poseidon Adventure,’ Victoria said, referring to the film she’d seen the previous week. Plates flew from the cafeteria tables and passengers toppled over, sliding along the floor. My mum took me with her to the toilet, telling me to hold onto a pillar, my arms barely reaching halfway around it, while she went inside the cubicle. There I remained as the floor tilted drastically one way, then the other, until my mum returned.

My dad remained calm throughout, barking orders to my sisters and me about who should stand where, even managing to finish his soup as the storm hit. To me he was like a cowboy from his favourite type of movie. A hard-talking, straight-walking man, not to be messed with. He had even bought a Stetson for our trip. He did lots of things that impressed me. He could drive and I already knew that was one of my life’s aims. He had a natural authority that put people into line, and I’d seen him fixing things with a treasure chest of tools, all of which he knew how to use. He paid for things from a brown leather pouch that hung from his belt. Now he was leading us on an adventure into the great unknown.

For the next few weeks we moved around the south of the country, pitching our family-sized tent, looking for land to buy. At night we ate boiled vegetables and salty cod in brightly lit restaurants, where the counters were varnished wood and the whitewashed walls broken by blue tiles. Glass fridges would be full of bowls of chocolate mousse and, after every meal, I’d order one. My cold spoon would plunge into the dessert, and for three or four minutes very little else would matter.

Our days were spent on deserted, pale sandy beaches in the dazzling Portuguese sun, searching for small silver fish in rock pools and being knocked over by the surf. The afternoons smelt of seaweed and salt. We’d take trips to old sea forts or make friends with kids on campsites. I never strayed too far from my mum, who would be grilling sardines or boiling a chickpea stew on a camp stove. My freckled-nosed, bob-haired sisters played in the parks with me before they wandered off together, seeking their own entertainment.

We drove through mountains covered with pine and cork trees, mangy cats staring at us from the roadside. We’d pass heavily burdened donkeys and oxen pulling carts led by short, moustachioed, grizzled men. Once, on an orange-tree-lined road, where the low crumbling houses with faded red-tiled roofs were few and far between, the van came to a forceful halt. Blood and feathers hit the windscreen. A chicken had boldly stepped out to cross the road, as chickens do, got three quarters o...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Note to Readers

- Contents

- Author’s Note

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Postscript

- Acknowledgements

- About the Publisher