![]()

1 . SEEING COLOR

“Color is my day-long obsession, joy, and torment.”

Claude Monet

Color is said to be contained within light, but the perception of color takes place in the mind. As waves of light are received in the lens of the eye, they are interpreted by the brain as color.

Colors that seem similar (such as orange and yellow-orange) do so because their wavelengths are nearly the same. Wavelength in a ray of light can be measured on a nanometer:

A ray of sunlight can be conceived of as being divided, like a rainbow, into a continuum of color zones. Each color zone contains more gradients than the mind can distinguish. The boundaries between colors are blurred, not sharply delineated. In the example below (fig. 1.1), the color yellow extends from the edge of yellow-orange on one side, across to where yellow merges into yellow-green on the other.

1.1 The full gamut of the the hue yellow extends from golden yellow (leaning toward orange) to lemon yellow (leaning toward green).

The perception of colored surfaces is caused by the reflection of light from those surfaces to the eye. A lemon appears “lemon yellow” to us because its molecules reflect light waves that pulsate at approximately 568 nm while predominantly absorbing waves of other frequencies. Lightwaves that are not reflected are not perceived as color (fig. 1.2).

1.2 On a yellow surface, the yellow wavelengths are reflected while other colors are absorbed and are therefore not perceived.

Color sensation can also be caused by gazing, directly or indirectly, at colored light. When different colored lights are combined (as on a theater set), the combination adds luminosity or brightness. Hence, light intermixing is considered an ADDITIVE COLOR1 process.

In contrast to mixing colored light, the intermixture of spectral colors in pigment tends to produce colors that are duller and darker than those being combined. (Spectral colors are those that approach the purity of colors cast by a glass prism or seen in a rainbow.) The more unalike the pigments being mixed, the darker the result. Darkness means less LUMINOSITY, thus mixing pigments is a SUBTRACTIVE COLOR process.

Intermixing pigments darkens color because the reflection and absorption of color in pigment are never absolutely pure. Although lemon yellow, for example, does reflect the yellow part of the SPECTRUM, its absorption of other colors is not total, as suggested in figure 1.10 on page 17. We see yellow predominantly, but subtle color reflections of all the other colors are also present. In the case of lemon yellow, a greenish cast is visible. (The diagram at right, figure 1.3, gives a truer picture of light reflected from a lemon-yellow surface.)

1.3 Color absorption in pigments is not total. Lemon yellow, for example, reflects visible amounts of green and smaller, less perceptible amounts of other colors.

COLOR OVERTONES AND THE PRIMARY TRIAD

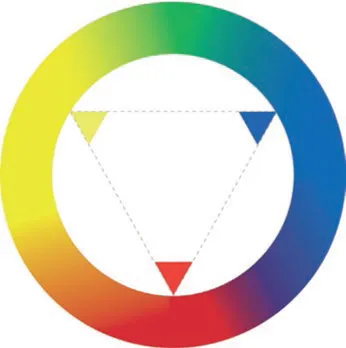

Throughout the history of color theory, there has been a tendency to arrange the HUE CONTINUUM in a circle. The extremities of the continuum, infrared and ultraviolet, resemble each other and seem to complete the sequence of HUES that proceeds gradually across the color zones of the spectrum. There is also, admittedly, a satisfying wholeness and symmetry to the circular configuration that suggests a sense of timeless rectitude. It also happens to distribute the hues in a way that facilitates an understanding of their relationships (fig. 1.4).When hues are arranged in a circle, one triad is considered more elemental than any other: the PRIMARY TRIAD of red, yellow, and blue.

While an infinite number of such triangles reside within the spectrum, the primary triad is unique because red, yellow, and blue are each, in theory, indivisible. They cannot be made by combining other colors. Conversely, all other colors can be made by combining two or more colors of the primary triad. But, as with our initial comments on color reflection, this is an oversimplification. Any color mixture also includes, along with the intended colors, their subsidiary color reflections. The simplicity and symmetry of the primary triad have a powerful appeal and, for some, an elemental significance.

1.4 The primary triad forms an equilateral triangle on the spectral continuum.

The idea that one can mix all possible colors from the primary triad is based on the assumption that there are pure pigments that represent the true primary colors. Unfortunately, none really exist. All red, yellow, and blue pigments are visually biased, to a degree, toward one or another of the colors that adjoin them.

It is commonly understood, for example, that green can be mixed by combining blue with yellow. But to make a vivid, seemingly pure green would be impossible if the only blue available were ultramarine. An even duller green would result if the mixture were based upon a combination of ultramarine blue and yellow deep (fig. 1.5).

1.5 The color overtones of ultramarine blue and yellow deep make it impossible to mix a vivid, spectral green from them.

Both ultramarine blue and yellow deep are biased toward colors that contain red (violet and orange, respectively). Red lies opposite green on the COLOR WHEEL. Colors that oppose each other directly on the color wheel are called COMPLEMENTARY HUES. Mixing complementary colors lowers the SATURATION (richness) and VALUE (luminosity) of the resulting tone. In other words, it has a dulling and darkening effect. Mixing ultramarine blue and yellow deep adds a latent red (the subsidiary reflections of both colors) which dulls and darkens the resulting green (fig. 1.5).

To mix a vivid green, choose lemon yellow and sky blue (fig. 1.6). Both are biased toward green and reflect insignificant amounts of red.

1.6 When lemon yellow and sky blue are mixed, a vivid green can result because both are biased toward green.

It should be understood that this discussion pertains to the mixing of pigments and, in particular, to the generation of secondary colors from the intermixing of primary colors. We don’t mean to suggest that all colors are physically achieved by combining primaries. To describe a green as “containing” blue is only literally true if that green has been made by intermixing blue and yellow pigments. Some pigments appear green in their pure physical form, e.g. chromium oxide green, but physically contain no blue. But all greens contain blue visually, and the blue element comes into play with color interaction, which we will cover in depth in Part Five.

A Musical Analogy

In this course we call a color bias an OVERTONE, a term borrowed from music. When a C string is plucked on a harp or struck on the piano, the string vibrates at a specific rate that causes our ears to hear a C. But in addition to the C, we also hear a weaker vibration: a G and (more subtly) an E (fig. 1.7). In fact, a diminishing succession of subvibrations always accompanies the strong pitch of a plucked string. As when colors are mixed, when individual musical tones are combined, so are their overtones. The result is a denser sound than one might expect. Adding a third and fourth note thickens the harmonic texture. The role of color bias in mixing paint parallels this acoustical phenomenon.

1.7 Each plucked note is accompanied by a series of subsidiar acoustical overtones.

Mixing a Secondary Triad

If we try to mix a vibrant SECONDARY TRIAD (orange, green, and violet) from a primary triad consisting of one specific red, one blue, and one yellow, some of the results will be compromised by con...