- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fashion Design, 3rd Edition

About this book

This book offers a thorough grounding in the principles of fashion design, describing the qualities and skills needed to become a fashion designer, examining the varied career opportunities available and giving a balanced inside view of the fashion business today.

Subjects covered include how to interpret a project brief; building a collection; choosing fabric; fit, cutting and making techniques; portfolio presentation; and fashion marketing and economics.

This third edition has been totally redesigned and extensively updated, with new images showing the latest fashion trends and coverage of new techniques.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fashion Design, 3rd Edition by Sue Jenkyn Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

DesignSubtopic

Fashion Design1•

Context

Context

It would hardly be possible to become an effective designer, stylist, or fashion journalist without contextual knowledge of the historical, geographical, economic, and social realms within which you plan your creative career. Colleges and universities offer a wide range of liberal arts, cultural studies, and business modules and electives to degree students. Attending seminars and writing essays are compulsory and assessable components of a fashion course and should not be regarded as time better spent in the studio. Lessons learned and insights gained from past analyses and theories, and from the practice of group discussion, intellectual inquiry, and academic writing, will prove inspiring and invaluable throughout school, and essential later in your career. Socio-economic conditions and the marketplace are in a constant state of flux and the context and motivations for clothing purchases can change many times in your professional life. Fashion designers cannot rely on intuition. Astute research and the ability to read the signs of change is the starting point for all design and good business, and will put you ahead of the game.

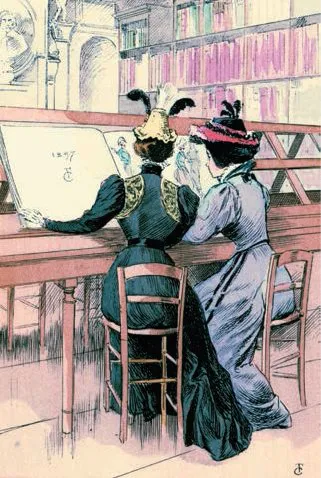

Fashion students in 1897 investigate clothing engravings in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

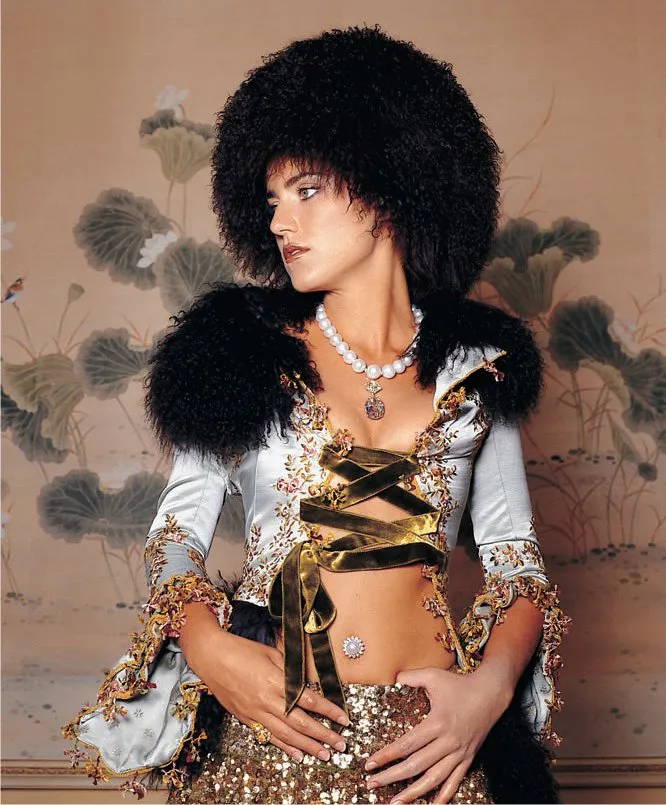

John Galliano playfully mixes historical, sartorial, and literary references in his designs. Here, Marie Antoinette meets Anna Karenina.

Historical context

Not all fashion courses offer fashion history as a subject. It is well worth the effort to acquaint yourself not only with garment names, silhouettes, materials, and the roster of legendary designers, but also with the underlying social, environmental, and technological conditions that led to changes in dress taking place. The fashion world is frequently inspired by the past; designers, display professionals, and stylists need to understand how to allude subtly to the silhouette or styling of a particular era or mix the palette of ideas in a new, and sometimes ironic, way. The time line on the following pages highlights significant costume changes and links them with their originators and contemporary events. It will help you to find research material and to recognize context and period when you observe clothes in paintings and films, and at the theater. Some universities and colleges have costume and fabric archives, and many have image banks. Fashion-school libraries often have bound copies of magazines covering many decades, as well as current journals.

The majority of museums offer reduced rates to students or free admission on certain days. Costume galleries are happy for students to come in and sketch quietly, but some have restrictions on photographing the garments on display. You can learn a great deal from drawing garments; being forced to look closely at proportion and line, and historical manufacturing methods, can be inspiring. Museums and collections, such as the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Victoria and Albert in London, have excellent websites that show garments too fragile to be put on display. Historical and contemporary fashion-research archives are available on the Internet, and images or background text can often be downloaded. A number of prestigious museums work closely with design colleges and will show small groups around archived collections if a tour is booked in advance.

Ethnic and folk costumes are also rich sources of inspiration. National and local galleries have extensive collections of these and it is still possible to find shops that sell both original and contemporary examples. Vintage-clothing shops frequently have superb twentieth-century clothes. It is inspiring to wear and admire the craftsmanship of the past and worthwhile being able to spot valuable gems and labels among the dross—even a pair of rare Levi’s can stand out in a pile of lifeless clothes, and could fetch a fortune at auction. You may discover fabric, trimmings, and accessories to recycle for use in your own work. Charity and thrift shops can be treasure troves of information on the construction of garments; it costs next to nothing to buy an old dress and then deconstruct it to make a pattern.

Film, theater, and television are great sources of inspiration, they not only demonstrate the clothes of an era or location, but also the hair, makeup, and styling, and the deportment and manners, that complement them. Sometimes it is the “mood” rather than the garment that can set the context for designs. From time to time fashion designers such as Jean-Paul Gaultier, Armani, and Donna Karan have been asked to design for film, stage, or television. Your ability to research and either authentically replicate or subtly update the looks of the past will be an invaluable asset. There is a list of leading international costume museums and collections at the end of this chapter.

Coco Chanel (1883–1971), developed her business from a small hat shop to a great couture house. Among the pioneering styles she introduced were the acceptable use of jersey and knitwear for social occasions, the ensemble suit, the little black dress, the pea jacket, bell-bottom pants, and bold costume jewelry.

Fashion time line

The uses of clothing

Fashion is a specialized form of body adornment. Explorers and travelers were among the first to document and comment on the body adornment and dress styles that they encountered around the world. Some returned from their travels with drawings and examples of clothing, sparking off a desire not only for the artifacts themselves, but also for an understanding of them. Eventually the study of clothing came to be an accepted part of anthropology—the scientific study of human beings.

Fashion frequently looks to the shapes and materials of the past as an inspiration for new styles. Vintage clothing is admired not only for the workmanship and detail that it is rarely possible to achieve today, but also triggers nostalgia for bygone lifestyles. This “emotional” aspect of clothing is an important element of design. Nevertheless, however much one might want to reintroduce the look of the corset or crinoline, it is wise to consider the social and political conditions and needs that made such items effective in their time and to apply similar analysis to contemporary styles. Anthropologists and ethnographers no longer have heated debates about the meaning of the rise and fall of hemlines in wartime, but they continue to throw light on the role that fashion plays in individual and group identity. The politics of identity are closely associated with the clothing we choose to wear. The focus is now on the uses of clothing in rites of passage and as manifestations of social preoccupations and cultural shifts. Today we have much greater freedom of choice than our predecessors had, and very few sumptuary laws that forbid or enforce the wearing of particular garments.

Cultural theorists and clothing analysts have focused primarily on four practical functions of dress: utility, modesty, immodesty (that is, sexual attraction), and adornment. In his book Consumer Behavior Toward Dress (1979), George Sproles suggested four additional functions: symbolic differentiation, social affiliation, psychological self-enhancement, and modernism. Each of these eight functions is discussed briefly below.

Utility

Clothing has evolved to meet many practical and protective purposes. The environment is hazardous, and the body needs to be kept at a mean temperature to ensure blood circulation and comfort. The bushman needs to keep cool, the fisherman to stay dry; the fireman needs protection from flames and the miner from harmful gases. Dress reformers have typically put utility above other aesthetic considerations. For example, in the 1850s the American publisher and suffrage pioneer Amelia Jenks Bloomer took issue with the impracticality of the crinoline and advocated the wearing of women’s trousers, called “pantalettes” or “bloomers.” The notion of utility should never be underestimated; consumers often choose clothes with concerns such as comfort, durability, or ease of care in mind.

In recent years, fitness clothing and sportswear—themselves originally utility items—have dominated the leisure-clothing market and become fashionable as indicators of health and youthful stamina.

Workwear often evolves in response to a physical hazard or environmental protection. This spiky suit was worn by a Siberian bear-hunter.

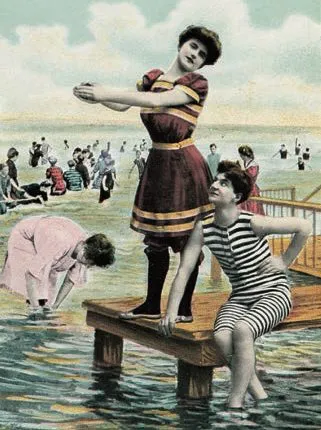

In Western society this type of beachwear is now considered absurd and antiquated.

In some Muslim countries, strict decency laws forbid women to reveal their bodies after puberty.

Modesty

We need clothing to cover our nakedness. Society demands propriety and has often passed sumptuary (clothing) laws to curb extravagance and uphold decorum. Most people feel some insecurity about revealing their physical imperfections, especially as they grow older; clothing disguises and conceals our defects, whether real or imagined. Modesty is socially defined and varies among individuals, groups, and societies, as well as over time.

In many Middle Eastern countries, debate still rages between liberals and fundamentalists as to how covered up women should be, and in many contemporary societies women still wear long skirts as a matter of course. Europeans are generally less inhibited than Americans, but the trend for “casual Fridays” and dressing down for the office has been imported from the USA. Club and beachwear reveals more of the body than at any previous time in history, and images of naked bodies are ubiquitous in advertising and the media.

Immodesty (sexual attraction)

Clothing can be used to accentuate the sexual attractiveness and availability of the wearer. The traditional role of women as passive sexual objects has contributed to the greater eroticization of female clothing. Eveningwear and lingerie are made from fabrics that set off or simulate the texture of skin. Accessories and cosmetics also enhance allure.

Many fashion commentators and theorists have used a psychoanalytic approach, based on the writings of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, to explain the unconscious processes underlying changes in fashion. The concept of the “shifting erogenous zone” (developed by J.C. Flugel, a disciple of Freud, in about 1930) proposes that fashion continuously stimulates sexual interest by cycling and focusing the attention on different parts of the body for seductive purposes, and that a great many articles of clothing are sexually symbolic of the male or female genitals. From time to time overtly sexualized clothing, such as the codpiece or the brassiere, come into vogue.

Adornment

Adornment allows us to enrich our physical attractions, assert our creativity and individuality, or signal membership or rank within a group or culture.

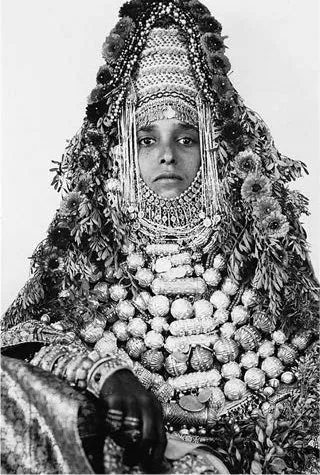

A girl from Yemen is decorated with flowers and ornaments on her wedding day.

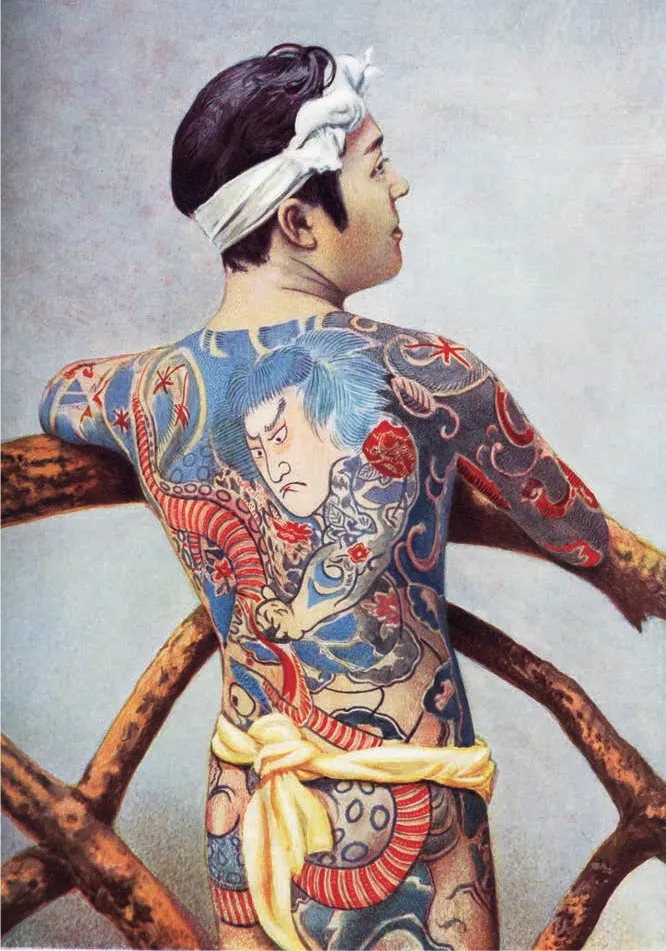

The tattoo is a permanent corporal adornment.

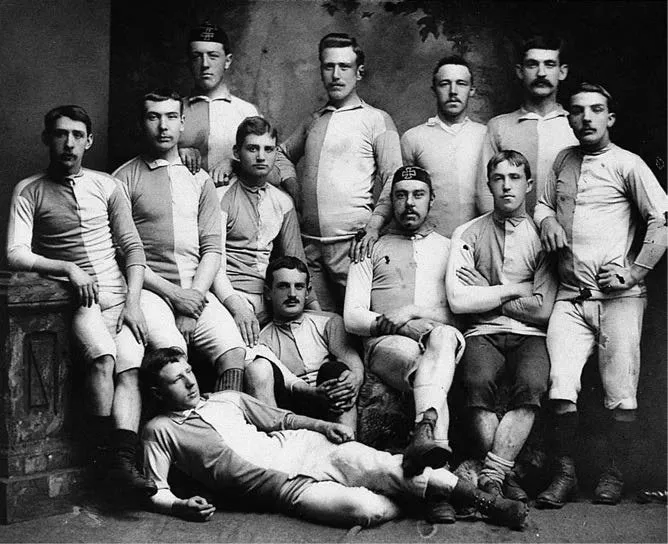

Soccer teams and their supporters dress alike in order to demonstrate allegiance and conformity.

The coronation gowns of George V and Queen Mary denote authority and status through their weight and the expense of the materials used.

At the other end of the social scale, a Pearly King and Queen from the East End of London dress in their regalia on a bank holiday.

Adornment can go against the needs for comfort, movement, and health, as in foot-binding, the wearing of corsets, or piercing and tattooing. Adornments can be permanent or temporary additions to, or reductions of, the human body. Cosmetics and body paint, jewelry, hairstyling and shaving, false nails, wigs and hair extensions, suntans, high heels, and plastic surgery are all body adornments. People generally, and young women in particular, attempt to conform to the prevailing ideal of beauty. Bodily contortions and reshaping through foundation garments, padding, and binding have altered the fashionable silhouette throughout the ages.

Symbolic differentiation

People use clothing to differentiate and recognize profession, religious affiliation, social standing, or lifestyle. Occupational dress is an expression of authority and helps the wearer stand out in a crowd. The modest attire of a nun announces her beliefs. In some countries, lawyers and barristers cover their everyday clothes with the garb of silk and periwig in order to convey the solemnity of the law. The wearing of designer labels or insignia, and expensive materials and jewelry, may start as demonstrations of social distinction, but often trickle down through the social strata until they lose their potency as symbols of differentiation.

Social affiliation

People dress alike in order to belong to a group. Those who do not conform to the accepted styles are assumed to have divergent ideas and may be mistrusted and excluded. Conversely, the fashion victim, who conforms without sensitivity to the rules of current style, is perceived as being desperate to belong and lacking in personality and taste. In some cases, clothing is a statement of rebellion against society or fashion itself. Although punks do not have a uniform, they can be recognized by a range of identifiers, such as torn clothes, bondage items, safety pins, and dramatic spiked hairstyles. This dress code was developed by the British fashion designer Vivienne Westwood as an anarchic jibe against the conventional, well-groomed fashions of the mid-1970s.

Psychological self-enhancement

Although there is social pressure to be affiliated to a group, and many identical garments and fashions are manufactured and sold through vast chain stores, we rarely encounter two people dressed identically from head to toe. While many young people shop with...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Context

- 2. From manufacture to market

- 3. The body and illustration

- 4. Color and fabric

- 5. In the studio

- 6. Assignments and assessments

- 7. The final collection—and beyond

- ...