![]()

Section 1 | DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIAL TRENDS |

Recent changes to the demographic composition of society have affected the ways people live and house themselves. The post-World War II image of the family, made up of a breadwinner father, stay-at-home mother and dependent children, was so persuasive that home builders could easily – and successfully – view the bulk of their potential clientele as a homogeneous buying block. A rapidly changing societal make-up and the emergence of new lifestyle trends have created demands for contemporary housing types that are small, flexible and efficient. Paramount among those changes is the rise of non-traditional and small households. The number of single, childless couples and single-headed families has increased several-fold in the past half century, meriting reconsideration of common housing prototypes.

In addition, the average age of the population in most nations has constantly been on the rise. The numbers of those aged 65 and over have more than doubled since the 1970s. This has created a market demand for accessible and adaptable dwelling forms and other living arrangements in response to senior citizens’ needs. The population involved in these changes has reached a critical mass, which validates the alternative approaches being explored by policy makers, designers and developers. Four dwelling concepts that respond to these social transformations are outlined in this section.

![]()

Chapter 1

LIVE-WORK RESIDENCES

The digital revolution of the 1980s led to a significant increase in the number of home-based businesses. In 2007, 24.4 million Americans worked either full-time or part-time from home, double the numbers recorded in 1990 (Penn 2007, Lee and Mather 2008). Furthermore, the US-based International Data Corporation estimates that nearly 2 million home-based businesses will be added by 2015 (Jaffe 2011). As result of economic shift, the future, some argue, could see the dispersal of work from traditional offices to homes.

The surge of live–work situations, which is also called ‘telecommuting’, can be attributed to the advantages that one gets from setting up such an office. Working from home offers a sense of freedom and flexible time management to the worker. It also eliminates the cost, stress and loss of time associated with commuting, leaving more time to pursue leisure activities. The question is: how can a live–work residence be designed to enhance both productivity and family life?

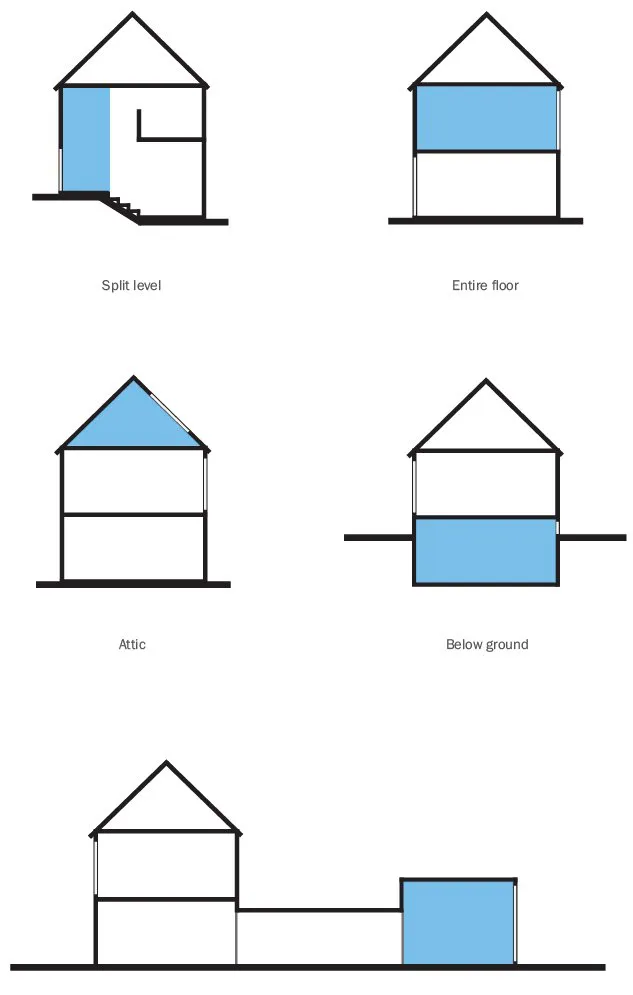

Integrating office and home can be a delicate task, since combining them can lead to a sense of entrapment, distractions and decreased productivity. When properly designed though, a home office can achieve the opposite, and seamlessly integrate work and family life. Factors such as noise, light, air quality and privacy must all be correctly balanced. The challenge of designing a successful live–work environment however, lies in the fact that a desirable home office has to do with programmatic requirements. An office designed for one telecommuter might be a single room, while other home offices might need to accommodate several employees and require both work areas and meeting rooms. In addition, some home businesses can operate retail outlets and so need visual and sound separation between the living and work spaces. Size is another programmatic issue. The type of work may dictate whether the office is an auxiliary structure, an entire floor or just a corner of a room.

One of the primary tools that designers use to create successful workspaces is separation. Most agree that work requires a space of its own, separate from other household activities (Senbel 1995, Dietsch 2008). Some designers have addressed this by creating a work area set apart from the primary living spaces by using passageways or staircases. If a larger office for multiple employees is needed, it is common to designate an entire level to be the office, typically the ground floor. If the homeowner wants to have a closer connection between the office and family spaces, then a split-level design can be suggested. This vertical division creates a visual separation, yet permits communication among household members in the different sections. At times, noise can become a distraction and therefore the split-level solution is only recommended in quieter situations. For smaller houses, interior dividers or partition walls that form workstations can also be used. The advantage of this approach is that these dividers can be moved around to reconfigure the work areas.

Figure 1.1:Possible locations of a home office in a dwelling.

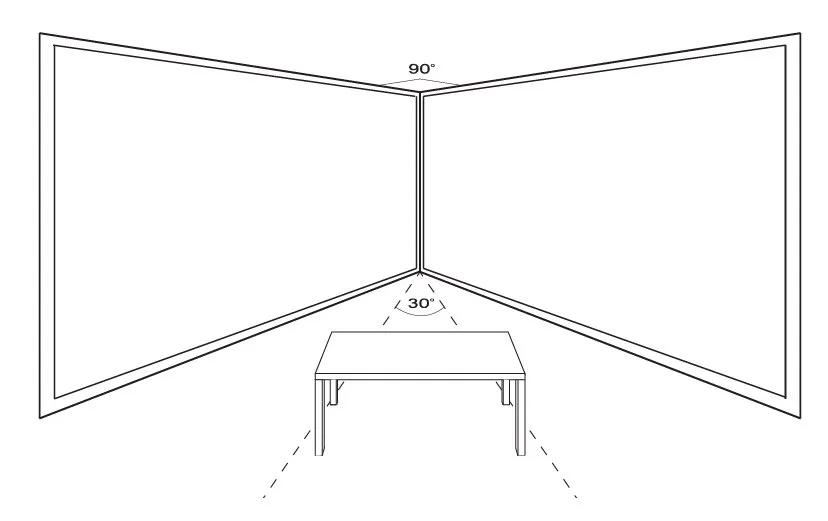

Figure 1.2The work space of a home office should be located in a glare-free area.

Beyond separating workspaces, there are other methods to improve working conditions in an office. In those with multiple workers, circulation is crucial to the cross fertilization of ideas. Recent studies have shown that an open-plan design allows for spontaneous discussions and for ideas to emerge (Becker and Steele 1995). Separating workspaces from one another in an attempt to increase efficiency may lead to the disruption of communication. Establishing distinct activity zones within the office is also a tool used by designers to create environments that encourage workers to move around. An office can be designed to feel open – which can be achieved by having two-storey spaces – and this can result in many arrangements, such as placing the office in a loft, or below the primary living spaces.

Placing offices near the facade with the most sun exposure is also important. According to studies, letting in ample natural light enhances productivity and feelings of well-being. Windows in those rooms should, however, be equipped with blinds to reduce extreme brightness and glare, and surface materials should preferably be non-reflective.

Where to locate the entrance to an office is another important decision a designer has to make. In some cases, the office may have its own independent entrance to allow maximum separation. This is usually done when the office has multiple employees or if it is a retail outlet. In other cases, the office can share an entrance with the residence. Although there is a lot of versatility in the design of entrances, most designers argue that there should only be a single entrance into a workspace for better internal circulation.

Due to ongoing economic shifts and further development in digital communication working at home is likely to become more common. All of this means that the design of live–work environments is a rapidly evolving area

DRIVING FORCES

•Economic shifts

•Avoid commute

•Advances in digital communication

•Flexible time management

INNOVATIONS

•Flexibility to accommodate one or several employees

•Flexibility to locate in various spots in the dwelling

•Use of demountable partitions

•Creating a separate entrance to the office

Section 1 | 1.1 LIVE-WORK RESIDENCES |

Project | House S |

Location | Breda, The Netherlands |

Architect | Grosfeld van der Velde Architects |

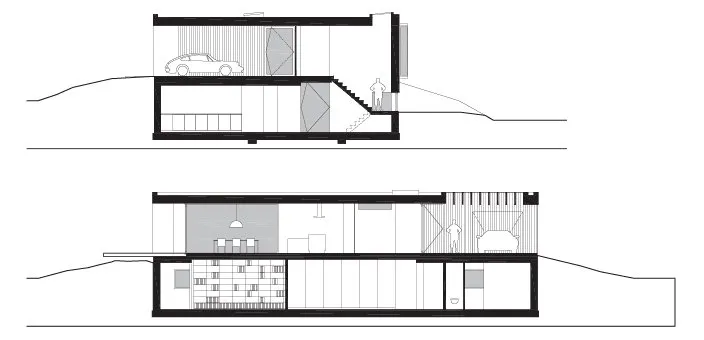

House S, with a floor area of 288 m2 (3,100 sq ft) over two levels, is built on a sandy hill overlooking the sea in the city of Breda in the Netherlands. The box-like house offers a scenic exterior view from the upper-level living spaces. The home office is located in the basement, where the owner works and meets clients.

The Dutch firm Grosfeld van der Velde Achitecten, who designed the building, placed the living area above ground to enhance both the relationship with nature and productivity. The intention behind the design was to distinctly separate the living and work areas so that each remains undisturbed by the other.

The below-ground working area contains an office space and a meeting room. A long horizontal window provides a scenic view and lets in natural light during daytime. Employees and visitors use a direct entrance to the office, where workstations accommodate them. The meeting room is connected to the office, but it has a more intimate setting and a wall-to-wall storage area.

Sections showing the location of the basem...