![]()

1.

Training to be an illustrator

Training to be an illustrator

“There is nothing to stop anyone from making art. The problem is what you do with it, and in what way it’s recognized. You’ll ultimately have to engage with the business of either applied art or fine art.” Peter Saville, graphic designer

“There’s applied art and fine art. The tools are irrelevant. It’s either applied: applied to somebody else’s problem or product, or it’s fine art: standing alone. The difference is really defined. It’s not a gray zone, in my opinion, it’s black and white.” Peter Saville, graphic designer

Images of our world are used to convey messages to global audiences. In this simple sign the idea of a male and female toilet is instantly communicated.

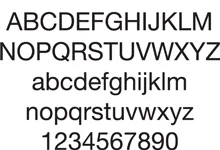

The Western alphabet, formed of 26 characters, is a formidable system of communication.

As with any creative enterprise, perhaps it is best to start this one with a blank space. Be it on screen or paper, the blank space is a place for the illustrator to think, to imagine, and to form thought. It is a powerful entity, a force to be reckoned with, a nothing that can become a something. It can fill the illustrator with hope and with fear; it can fill them with frustration and even despair. It can also, time and again, serve as a portal for the illustrator to enter a creative world where an image can be rendered, where a subject can be explored, and where a solution to a client’s problem can be found.

This blank space is not an entity that people working in other professions engage with on a daily basis. The accountant, the lawyer, and the doctor are not expected to find a “new” answer to problems that they face regularly in their areas of expertise. On the contrary, they are expected to have an extensive knowledge of existing accounting, legal, or medical systems, knowledge that they skillfully apply to their work. Although innovation does take place within their fields, it is essentially an isolated, risk-averse activity that may or may not lead to fruition. By contrast, the illustrator, who earns a livelihood by making specific types of imagery, has no rulebook, no right or wrong way of doing things, no set answers, and faces the real risk of failure on a daily basis.

The illustrator’s job is to create a something from a nothing, to encapsulate an idea that communicates to an audience in an innovative way that is also articulate. Though systems surround visual language, and theories define the process of communication, it is not enough to have an extensive grasp of these systems and theories—simply regurgitating them will not do. The training for an illustrator requires that they explore key areas of their subject, both practically and intellectually, until they can competently reassemble them in a fashion that is peculiar to them, that carries their authorship, and that is imprinted with their own particular artistic and intellectual vision.

The writer, too, has an intimate knowledge of the blank space, be it the white surface of the paper or the luminous glow of the computer screen. They too must find their way into this space, to map their thoughts and ideas, but with a different system—the system of written language. It is no surprise , therefore, that these two professions, one using pictures and one using words, have been intertwined for so many years; these two, born of the same starting point, have forged a union that, when functioning properly, becomes a force far greater than the sum of its parts.

A blank sheet of paper and a pencil are often the starting point for tackling a creative brief.

This union between picture and word is called “graphic design”; it is arranged, ordered, and conceptually driven by graphic designers. This subject, vast in reach, has saturated all areas of culture. We see graphic design in newspapers, books, advertisements, and corporate literature; we see it accompanying the music that we buy, on television, and in film; we see it within the physical environment that we inhabit, on the clothing we wear, and on our navigational signage systems. It is very hard to imagine a world without graphic design; it has become integral to the way in which we communicate, function, and organize ourselves as human beings.

Contextualizing illustration within graphic design

As a subject, and as a defined profession, the term “graphic design” has existed for a relatively short time—since the end of the Second World War. Prior to this, scribes, religious personnel, printers, fine artists, and, most recently, commercial artists, had dealt with the arrangement of pictures and words for mass public consumption. After the war, and due to the breadth and depth of its reach, the business of “communication design” fragmented into distinct areas of specialism. Illustrators appropriated the territory of the constructed image (be it drawn, painted, printed, collaged, or computer-generated); typographers appropriated the letterform; advertising art directors controlled the generation and formation of the publicity concept for products and services; photographers monopolized the photographic image; and of course graphic designers were in charge of orchestrating (and in many cases, generating) any and all of these elements, both intellectually and artistically, into dynamic and articulate messages for the purpose of “identification, information, and instruction, presentation, and promotion.” These messages have appeared ever since in print, on television, in the cinema, on books, in the environment, on packaging, and, most recently, on the internet via the desktop computer and the digital phone.

Volkswagen Beetle advertisement by Helmut Krone and Julian Koenig. Lithograph, 1960. This poster from New York advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach employs a central concept that is displayed in a light and playful way.

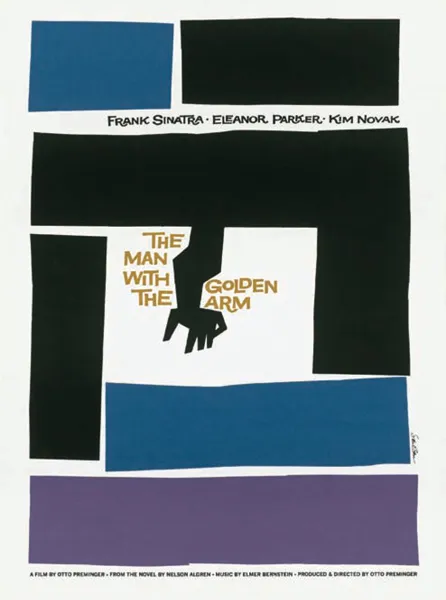

The Man with the Golden Arm by Saul Bass. Poster, 1955. Commissioned by Otto Preminger Films. The work of American illustrator Saul Bass, who was particularly famed for iconic film posters such as this, pervaded many areas of contemporary communication design discourse.

Chapters 4 to 7 cover the use of illustration within all of these areas—editorial, publishing, corporate design and advertising, and light entertainment. As we shall see over the course of this book, the continuing history of illustration exists within the history of graphic design; it is embedded, intertwined, and coreliant.

Pictures and words—similarities and differences

We have ascertained that there is a powerful connection between word and image, facilitating the creation of “graphic design.” Pictures and words possess particular qualities, both apart and in common, that assist in their power to communicate together within such a diverse arena.

The picture has the power to:

- Communicate instantaneously.

- Communicate to a global audience, regardless of age, location, or era.

- Locate the viewer within the image.

- Represent literally the human experience of seeing.

- Visually delight, again and again.

- Be arranged sequentially to communicate narrative.

- Connect instantaneously with emotion, memory, and experience.

- Delight through shape, color, and form.

Esquire cover, art direction by Henry Wolf; photography by Ronny Jaques, 1953. Commissioned by Esquire. This magazine cover shows the dominance of the concept in 1950s American art direction.

Illustration by Arpi Ermoyan for the story “Heart’s Ease,” written by Sarah-Elizabeth Rodger, in Woman magazine, 1952. The new-found liberation of the postwar years is clearly visible in this illustration from one of the numerous romance magazines available.

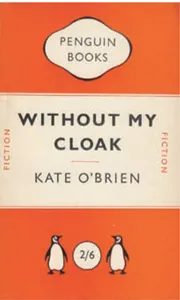

Without My Cloak, written by Kate O’Brien, cover design by Jan Tschichold. Penguin, 1949. The work of renowned German typographer Jan Tschichold for Penguin Books shows the development of typography as a powerful stand-alone element that, coupled with a color-coding system, also serves to identify the genre of the writing.

Photo...