![]()

Section 1 Animal fibres

Numerous species of animal have provided humankind with fibres for warmth and protection. The most common fibres are from farmed sheep and goats. Less common, and specific to particular geographic areas, are the fibres from the musk ox (qiviut) and yak. These fibres, together with the luxurious but now illegal down from the Tibetan antelope, are all from the Bovidae (cloven-hoofed) family of animals.

Animals from the Camelidae family that are a source of fibre include the llama, alpaca, vicuña, guanaco and camel, both farmed and wild. Angora rabbits (Leporidae family) are bred for their fine hair. Silk from the Insecta class of Animalia is predominantly farmed, but may also be wild.

Animal fibres consist largely of proteins. Not all fibres have the same properties; even within a species there is no consistency, with differences in fineness, diameter and structure.

The global market

Animal fibres represent a tiny percentage of the global fibre industry. Sheep’s wool is the most popular, representing a little over 1 per cent of total global fibre production. The remaining fibres (including silk) are considered as luxury or craft fibres, and as such represent less than 1 per cent volume of the global fibre industry. However, they play a significant role in the high-value apparel market, with greater profit margins than their volume might suggest.

Luxury fabric production has seen a threefold increase in production over the last 30 years.

Recycling

Historically, animal fibres have been integral to the textile recycling industry, long before recycling and upcycling became part of contemporary fashion vocabulary.

Animal fibres are the most reused and recycled of all fibres. Garments are worn more often and kept far longer. The average wear-life is said to be 50 per longer more than garments of any other fibre composition. Clothing is more valued and less often discarded; when discarded, it is mostly sold on to dress agencies, vintage shops or donated to second-life stores. The donation rate of garments made from animal fibres is five times greater than their share of the global virgin fibre industry.

Sustainability

As mentioned, sheep and goats are the two largest fibre-producing groups of animals and, as ruminants (cud chewing), are contributors to greenhouse-gas emissions. Vaccines can be used to inhibit gut organisms, reducing methane emissions by nearly a quarter. Ecological and animal husbandry concerns are dependent on farming practices; certified organic and or ethical farming methods are an alternative to conventional sheep and goat farming.

Animals in the Camelidae family (camelids) are not ruminants and do not contribute to greenhouse-gas emissions. In their native habitats they help to sustain the income of poor local communities and are well looked after.

Silkworm (sericulture) and Angora rabbit farming is cruel, but there are ethical alternatives. Ahimsa peace silk allows the chrysalis to metamorphose into a moth before the cocoons are collected and processed. The ethical alternative to Angora farming is the traditional method of regular combing rather than plucking. Combing frees up discarded hair, which is essential grooming for Angora rabbits, as well as producing superior-quality fibres for the fashion industry.

Unprocessed alpaca wool. The United States classifies alpaca wool into 22 colours, while Peru classifies it into 52 colours. Black and white are the most expensive.

Wool

These ringlets – scoured, washed and dyed wool from a Wensleydale sheep – demonstrate the fibres’ natural curl and lustre.

Wool is the ultimate natural chameleon fibre, embodying many diverse aspects.

Wool can be satisfyingly soft, warm, cosy and sensuous, or rugged, tough and functional, while its inherent drapability allows its finest fibres to appear lustrous, sleek and elegant.

The history of wool

Our relationship with this traditional fibre is almost as old as civilization itself, and wool’s unique thermally responsive and insulating qualities remain as relevant today as at any time in history.

Early history

The use of felted wool for clothing can be traced back tens of thousands of years. Taking inspiration from the matting of the fleece that occurs naturally on the animal’s back, primitive cultures worldwide developed processes of wetting, massaging and pressing wool to produce a dense, matted felt ‘blanket’ that could be cut or manipulated into varying thicknesses, or moulded into shape. Felted wool was commonplace in China and Egypt long before the technologies for spinning and weaving were developed.

A contemporary expression of a traditional process, this red ‘Boxing’ dress was hand felted by US-based German artist Angelika Werth. The dress was one of a series of 12 ‘Madeleines’ conceived by the artist to express specific personalities engaged in athletic pursuits. This Baroque-inspired example exploits the sculptural nature and robust qualities of traditionally felted fine merino wool.

However, wool was the first animal fibre to be woven, and by Roman times, wool, together with linen and leather, clothed Europe. Cotton was seen as a mere curiosity, while silk was an extravagant luxury. It is believed that the Romans invented the carding process to brush, tease and comb the fibres into alignment to facilitate the smoother spinning and weaving of the yarn. It is also believed that the Romans were the first to selectively breed sheep to produce finer, superior qualities of wool.

Pre-industry

By the beginning of the medieval period, the wool trade was the economic engine of both the Low Countries and central Italy, and relied on English wool exports for cloth production. Wool was, at this time, England’s primary and most valuable export commodity. Pre-Renaissance Florence’s wealth was similarly built on the textile industry, which guided the banking policies that made that city the hub of the Renaissance.

By the time of the English Restoration, in the mid-seventeenth century, English woollens had begun to compete with silks in the international market. To help protect this lucrative trade, the Crown forbade its new American colonies to trade wool with anybody other than the ‘mother’ country.

Spain’s economy was similarly reliant on this valuable export, to such an extent that the export of merino lambs was only permitted by royal consent. Spanish merino sheep, with their finer-quality fleece, became the most desirable breed. A great majority of today’s Australian merino sheep originated from here, via a circuitous route as part of a gift to the Governor of the Dutch Cape, and then on to Australia, where the vast areas of dry pasture perfectly suit fine-wool sheep breeds. The Spanish also introduced sheep to Argentina and Uruguay, where the climate and pastures were favourable for their growth and expansion, and today they represent a sizeable percentage of the two countries’ export revenue.

Modern times

By the mid-nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution had turned Bradford in Yorkshire into the centre of the industrialized world’s spinning and weaving industry. Bradford’s insatiable appetite for fine woollen fibres is said to have built and maintained Australia’s colonial economy. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Australian sheep rearing and its wool trade had usurped Europe’s industry, and to this day Australia remains the most important global producer of wool.

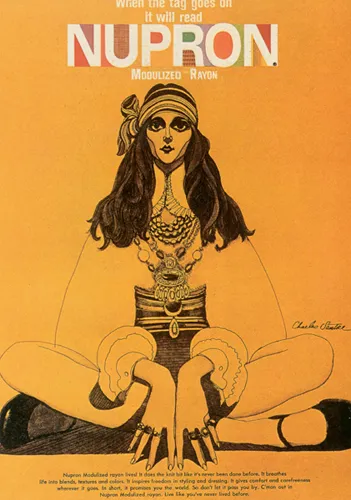

The end of World War II was a catalyst for many socioeconomic and political changes. Man-made materials were in tune with the modern world of working women, busy lifestyles and greater social mobility. New sporting and leisure pursuits encouraged the use of easy-care fabrics. The synthetics first developed between the 1930s and 1940s were in general use throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and were considered sophisticated and in tune with postwar values.

Acrylic was developed as a substitute for knitted wool, while polyester, or Terylene as it was known in tailoring, was the perfect medium for drip-dry, non-iron, easy-care lifestyles.

By contrast, by the mid-1960s, new socio-political movements were emerging in North America and Western Europe. The flower-power movement questioned the values of the West – especially materialism. In the search for a new world order, many alternative lifestyles and cultures were embraced. One outward sign of this was a revival of traditional crafts. Wool and cotton, both natural and traditional fibres, were favoured, preferably if homespun, and ideally with an organic pedigree. It may be said that the hippy movement was instrumental in jump-starting the wool revival.

The hippy movement of the 1960s questioned Western values and was inst...