![]()

Fig. 1

Aerial view of Venice

The city of Venice was built on a series of low islands that were gradually connected via an intricate system of canals, bridges and walkways. Its buildings were erected by driving huge tree trunks into the soft mud of the shallow lagoon. This view features the civic and religious centre of Venice around St. Mark’s Square in the foreground (see also the plan on page 20).

1

‘The Most Serene Republic’: Venice at the Outset of the Renaissance

Given the unlikely location of Venice among the watery recesses of a lagoon a mile or so off the coast of northeast Italy, it is no surprise that it possessed a unique culture, at some remove from the social mainstream of Europe (FIG. 1). If the city was not quite ‘another world’, as the fourteenth-century poet Francesco Petrarch described it, it was certainly a mediator between worlds. In the pre-Renaissance centuries, Venice had relied less on a land empire than on the predominance of its merchant fleet at sea. Trading silks and spices from the East with wool and metals from the West, Venice was necessarily dependent on the flow of import and export commodities. The city possessed few raw materials of its own; and it lacked a grand Imperial history, like Rome or Constantinople (modern Istanbul). Perhaps as a result, Venetians developed a heightened sense of the importance of ‘tradition’ and were particularly active in the invention of stories about their own past. They came to share a series of patriotic narratives or myths that highlighted the city’s arbitration between powers and its special sacred destiny.

Origins: Myths of Venice and the basilica of St Mark’s

One particularly favoured story focussed on an act of Venetian peacemaking between the two most powerful leaders in Europe, Pope Alexander III and the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, in 1177. The Venetian doge Sebastiano Ziani (reigned 1172–1178) offered shelter to the pope and then helped to smooth over the conflict between the two rulers. He received a series of ceremonial gifts, or trionfi, from Alexander for his efforts, including a sword and an umbrella, which were regularly displayed in centuries to come, especially when the doge processed around the city on Holy Days or in the fulfilment of one or other of the city’s many civic rituals (FIG. 2). • e story also became a favoured subject in visual art, appearing in illuminated manuscripts and also in large-scale narrative paintings decorating the main room of the city’s Ducal Palace, known as the ‘Alexander cycle’ (see FIG. 126).

Another story made the success of Venice appear as pre-destined from the period of early Christianity. From the twelfth century onwards, it was understood that the city had been founded on 25 March 421, the feast of the Annunciation to the Virgin. This supplied an account of Venice’s antiquity and also of its special and continuing protection by the Mother of God herself. The idea of Venice’s sacred destiny was reconfirmed by the arrival of the relics of St Mark from Alexandria in Egypt in 829. According to a thirteenth-century legend, Mark had already been told by an angel that his remains would come to Venice. This is the source of the many subsequent images set up around the city showing a winged lion, symbol of St Mark, holding an open book with the words ‘Pax tibi Marce, evangelista meus’ (‘Peace unto You Mark my Evangelist’). The period between 1100 and 1500 was key to the process of ‘mythogenesis’ in Venice and was focussed particularly on the great building erected at the eastern end of the city’s main piazza to house the relics of the saint: the basilica of St Mark’s (FIG. 3).

Fig. 2

Matteo Pagan

Detail of Procession in St Mark’s Square on Palm Sunday

1556–9. Woodcut (eight-block xylograph). Museo Correr, Venice.

Doge Lorenzo Priuli (reigned 1556–9) is shown processing. He wears the characteristic oddly shaped corno or ducal hat, and is further identified by an inscription describing him as ‘Il Serenissimo Principe’ or ‘The Most Serene Prince’. His followers carry the ceremonial umbrella and sword awarded by Pope Alexander III some 380 years earlier. The procession is watched by crowds of onlookers, though tellingly the women are confined to the interior of the buildings, viewing the scene from upper windows.

Fig. 3

St Mark’s Basilica

Erected above previous structures between 1043–73; west facade from the thirteenth century, with the six crowns added ca. 1400, Venice. The four bronze horses seen in this photograph are copies, while all but one of the mosaics are from the post-Renaissance period. Lste antique marble reliefs featuring Hercules can be seen between the arches.

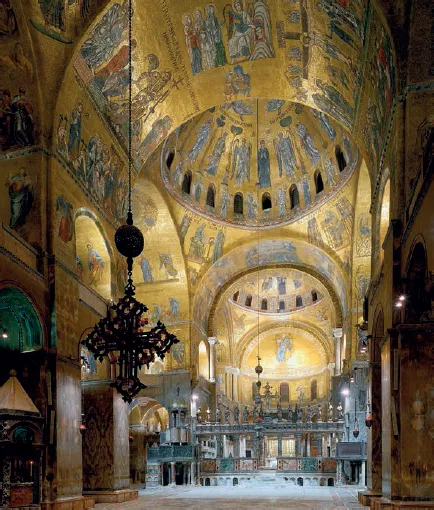

Many of the Renaissance works discussed in this book owe a debt to the example of St Mark’s, or make a definite and explicit reference to the church. Along with the Ducal Palace discussed below, the building stood at the very heart of the city, in both a physical and symbolic sense, functioning as a public monument to its religious and political identity. From the outset this extraordinary building laid more emphasis on the civic power of the city than on the independent identity of the Christian Apostle to whom it was dedicated. St Mark’s was not the Cathedral of Venice but rather the ‘doge’s chapel’, and from the mid-fifteenth century onwards it was physically attached to the Ducal Palace, where the doge lived and the government of Venice was enacted. The ultimate dependence of the church on the seat of city government just to the south is indicative of the Venetian approach to religion, which was carefully controlled by the needs and demands of the state. If Venetian religion was assertively independent of the wider Christian church in both its Roman and Orthodox manifestations, the layout of St Mark’s, with its central plan and five domes, drew pointedly on the lost sixth-century church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. This was an association which expressed Venice’s long-standing connection with the Byzantine Empire of which it had formerly been a part, and with which it remained closely connected, given that its lucrative spice trade in the East was in great part conducted through Byzantine territories.

Much else about the building was intended to appear as ancient or time-hallowed. The extensive cycles of mosaics commissioned to adorn its facade and inner ceilings suggested connection with the similar decorations in early Byzantine churches, such as the sixth-century Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (FIG. 4). Although the initial teams of mosaicists employed following the erection of the church in the eleventh century were imported from Byzantium itself, a thriving local school soon grew up who were so skilled in their emulation of the Eastern craftsmen that it is now difficult to tell their works apart. In The Stones of Venice (1851–3), the great Victorian John Ruskin noted how the securing of the slabs of multi-coloured marble revetment erected on the lower walls of the church were deliberately left open to view (‘the confessed rivet’). Ruskin, who deplored the coming of the individualistic culture of the Renaissance to the city, especially praised this respectful re-use of precious materials imported from abroad as a characteristically Venetian practice. The (unknown) architect at St Mark’s, Ruskin went on, readily put his own ideas aside, given his ‘care for the preservation of noble work … and more regarded the beauty of his building than his own fame’. For Ruskin, this selfless respect for the past had a quasi-religious dimension; but it also expressed a communal approach that reflected the political and social values of the Republic itself.

There was, however, a much more appropriative dimension to the assemblage of older pre-worked materials from elsewhere at St Mark’s: many of the objects displayed on the facade were plunder from the Sack of Constantinople by European Crusaders in 1204, in which Venice had fully participated and from which it subsequently greatly benefited in political and economic terms. As Ruskin acknowledged, these precious objects were elevated as ‘the trophies of returning victory’, making the facade appear more like ‘a shrine at which to dedicate the splendour of miscellaneous spoil, than the organized expression of any fixed architectural law or religious emotion’. The spolia displayed at St Mark’s proposed an image of ultimate Venetian victory and dominion, but one based on an ideal of social and religious concord between different elements. The plunder from Constantinople reinforced the earlier modelling of the church, giving further credence to the idea that Venice, with its growing empire, was the natural heir to the glories of Byzantium: one that inevitably intensified again following its final fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. But this notion did not entail stylistic uniformity. The Venetians proudly displayed classicizing marble reliefs featuring Hercules and four bronze horses from the late antique period on the facade, among the parti-coloured marbles of the portals and a growing forest of Gothic pinnacles, finials and crockets.

Fig. 4

St Mark’s Basilica

See Fig. 3. Interior view from the central nave towards the crossing and apse. The extensive mosaic cycles rising up above the marble revetments on the lower walls were begun in the eleventh century.

The Ducal Palace and the Porta della Carta

Such an approach appeared always to validate ‘tradition’ and the workmanship of many other cultures of the past, while at the same time suggesting that this ended with the present victory and ongoing predominance of Venice itself. The incorporation of different elements or borrowings into the Venetian present discouraged artistic individualism, or sought to accommodate it within a panoply of equally acceptable styles. Diversity, both in the sense of material and form, better expressed the idea of the city as a free and equitable Republican community with a long and illustrious past. Something similar is at play in the Ducal Palace, where the unknown architects engaged in stylistic pluralism from the outset (FIG. 5). If St Mark’s was a building in the Byzantine style that was gradually Gothicized over the centuries, the Ducal Palace was only begun in the mid-fourteenth century, and was largely complete a little over a century later. Despite this much shorter gestation, allusions to traditionally distinct architectural traditions were central to its conception, with Gothic and Islamic elements freely combined, probably to suggest overlapping spheres of Venetian influence between West and East. The city’s habit of appropriation and amalgamation means that we cannot precisely pin down the derivation of the different elements included. The traceries above the double rows of colonnades on the lower part of the building, for example, owe something, at least, to Moorish screen walls. And if the overall effect is unmistakably Gothic, the inlaid lozenge pattern of red and white marble tiles on the walls nonetheless has a precedent in Persian decorative tradition. The various elements associate freely together as if they are knowing references or quotations, and this lightness of touch seems actively to deny any sense of the building’s inner depth or structure. The dense repetition of elements in the lower colonnades, which contrast in a vibrant two-to-one rhythm, like the subtle variations within a given surface – each pattern of tiles is slightly different – generates a rich and vibrating surface that enters into a fluid relationship with the waters of the Basin beneath.

Fig. 5

Ducal Palace View of the south front from St Mark’s Basin, Venice.

Begun in 1341.

Fig. 6

Filippo Calendario (?)

Venecia

Before 1355. Stone relief on the west front of the Ducal Palace, facing the Piazzetta, Venice.

The Venetian state is equated with the cardinal virtue of Justice, shown as a woman holding a sword seated on a Solomonic throne with two ...